적색 및 황색 파프리카 추출물의 항산화 활성 및 멜라닌 생성 억제 효과

Abstract

The aims of this study were to evaluate and compare the antioxidant activities and melanin suppression capabilities of red and yellow colored paprika extracts (WRP and WYP) and to explore their potential as functional natural ingredients. The antioxidant activity was evaluated using the DPPH radical scavenging assay. WRP demonstrated dose-dependent increases in DPPH radical scavenging activity of 5.46%, 9.92%, 24.23%, and 36.11%, while WYP exhibited concentration-dependent increases of 6.33%, 13.40%, 28.71%, and 40.41%. Furthermore, both WRP and WYP were assessed for tyrosinase inhibition. At a final concentration of 4 mg/mL, WRP and WYP showed inhibitory activities of 46.54% and 47.52%, respectively. Cell viability of B16F10 cells was determined using the MTT assay after treatment with WRP and WYP, revealing melanin inhibition in B16F10 cells at concentrations of 100 and 200 μg/mL without inducing cytotoxicity. Although no significant differences were observed between WRP and WYP in terms of antioxidant activity and tyrosinase inhibition, both WRP and WYP were expected to be used as functional food ingredients exhibiting antioxidant and anti-melanogenic properties.

Keywords:

paprika, antioxidant activity, oxidative stress, tyrosinase inhibition, melanogenesis서 론

호기성 세포의 대사 결과 생성되는 자유라디칼은 강력한 산화제로서 DNA와 같은 생물학적 분자구조를 손상시켜 인간에게 심혈관 질환, 암 및 알츠하이머 등과 같은 다양한 질병을 유발한다(Kander MC 등 2017; Poprac P 등 2017). 또한 활성산소에 의한 산화적 손상은 세포의 돌연변이나 퇴화를 유발하고 점진적인 세포 내 자유라디칼의 축적에 의한 산화적 손상은 세포고사와 이에 따른 각종 질환의 발병율을 가속화 시킨다(Loft S 등 1994). 최근에는 이와 같은 유해 활성산소를 제거함으로써 질환을 완화시키는 시도가 활발해지고 있으며 이와 관련해 산화방지 효능이 있는 다양한 소재들이 주목 받고 있다(Eriksson CE & Na A 1996; Pitchumoni SS & Doraiswamy PM 1998; Silveria ER & Moreno FS 1998; Vatassery GT 1998). Liu RH(2003)는 과일과 채소에는 비타민 C와 비타민 E뿐만 아니라 카로티노이드, 리코펜, 플라보노이드, 탄닌 및 카테킨 등의 페놀 화합물과 같은 다양한 항산화 성분이 함유되어 있기 때문에(Steinmetz KA & Poter JD 1996; Joshipura KJ 등 2001) 이를 섭취하였을 때 노화 억제와 성인병 및 만성질환, 암, 심혈관계 질환 등 여러 질병들의 발병률을 감소시킬 수 있다고 보고하였다(Fernández-Sevilla JM 등 2010; Poojary MM 등 2016). 또한 파프리카에도 다양한 페놀류, 카로티노이드 및 비타민 C 등의 기능성 성분이 함유되어 있어 높은 항산화 효과가 있다고 알려져 있다(Marin A 등 2004; Deepa N 등 2006; Kim JS 등 2011; Chávez-Mendoza C 등 2015).

또한 피부색소 형성의 주요 원인인 자외선에 의해 발생된 활성산소가 피부색소 형성을 촉진한다는 메커니즘이 밝혀지면서 활성산소를 소거하는 것이 멜라닌 색소 형성억제에 효과적이라는 연구보고가 있으며(Tobin D & Thody AJ 1994; Eberlein-König B 등 1998), 이에 따라 항산화 성분은 연속적인 산화과정에 의해 생성되는 멜라닌 색소 형성을 막을 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 활성산소 소거를 통해서 멜라닌 색소 형성을 막을 수 있는 미백 소재로서의 가능성이 다각도로 제시되었다(Han YS & Jung ES 2003).

파프리카(Capsicum annuum L.)는 가지과, 고추종의 한해살이 식물이며 나라에 따라 paprika, sweet pepper, pimento 그리고 bell pepper 등으로 불리고 우리나라에서는 한국원예학회의 용어집에 따라 단고추로 분류되었다(Hwang JH & Jang MS 2001). 파프리카는 다양한 색상으로 존재하는데, 그중 적색 파프리카는 전체 생산의 약 40%를 차지하며, 당 함량이 높아 단맛이 높고 비타민, 카로티노이드, 플라보노이드 및 토코페롤과 같은 식물유래 생리활성물질을 함유하여 각종 암이나 심혈관계 질환을 예방하는 것으로 알려져 있다(Deli J 등 2001; Jeong CH 등 2006; Park YJ 등 2017). 파프리카에 함유되어 있는 β-카로틴은 눈 건강 및 암 예방에 효과적이며(Craft NE 등 1993), 루테인과 제아잔틴은 노인성 황반변증과 초기 동맥경화 예방에 효과가 있다(Seddon JM 등 1994; Dwyer JH 등 2001). 또한 캡산틴은 동맥경화 및 심장질환의 위험 감소 효과가 있고(Aizawa K & Inakuma T 2009; Aizawa K 등 2009) 파프리카의 중요한 항산화 성분인 비타민 C와 E는 β-카로틴과 함께 활성산소에 의한 세포 내 DNA 손상을 막는다고 보고되었다(Hunter DJ & Willett WC 1994). 이밖에도 파프리카는 pH, 열 및 빛에 안정한 성질을 가지고 있는 알칼리성 식품으로 매운맛이 덜하고 독특한 향이 있으며(Jung JY 등 2004), 일반 피망보다 2∼3배 크고 생식용, 샐러드 및 고기요리의 부재료 등으로 활용도가 높다(Ko WH 2005). 현재 파프리카를 이용한 식품으로는 유럽의 소세지(Aguirrezábal MM 등 2000), 소스(Lee KY 등 2022), 샐러드드레싱(Choi SN & Chung NY 2015) 및 치즈(Francisco José Delgado 등 2011) 등이 있고 국내에서는 파프리카즙 첨가 생면(Hwang JH & Jang MS 2001)이나 증편(Jung JY 등 2004) 그리고 고춧가루 대용품으로 파프리카를 이용한 김치(Kim HJ & Jhon DY 2001) 등이 개발되었다. 이렇듯 파프리카를 이용한 식품의 가공 및 개발에 관한 연구는 보고되었지만, 파프리카의 미용 기능성에 대한 체계적인 연구는 전무한 실정이다.

이에 본 연구에서는 색상이 다양한 파프리카 중에서도 적색과 황색 파프리카 추출물을 제조하여 항산화와 미백 활성을 검증하고 이를 바탕으로 파프리카의 기능성 식품 소재로서의 이용 가능성을 검증하고자 한다.

재료 및 방법

1. 실험재료 및 시약

적색과 황색 파프리카는 농협 하나로 마트 창원점(Nonghyup Hanaro Mart, Changwon, Korea)에서 구입하였다. 본 실험에서는 적색과 황색 파프리카의 항산화 및 멜라닌 생성 억제 효과를 평가하기 위해 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl(DPPH), 비타민 C, L-tyrosine, mushroom tyrosinase, arbutin, thiazolul blue tetrazolium bromide(MTT) 및 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine(IBMX)를 Sigma-Aldrich(St. Louis, MO, USA)에서 구입하였고 B16F10 세포를 배양하기 위한 fetal bovine serum(FBS), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium(DMEM), penicillin-streptomycin 및 phosphate-buffered saline(PBS)는 Welgene Inc.(Daegu, Korea)에서 구입하였다. Dimethyl sulfoxide(DMSO)는 Junsei chemical Co., Ltd.(Tokyo, Japan)에서 구매하였고, 94.5% 에탄올은 Daejung(Seoul, Korea)에서 구매하여 사용하였다. 또한 B16F10 세포는 한국세포주은행(KCLB, Korea Cell Line Bank, Seoul, Korea)에서 분양받았다.

2. 적색과 황색 파프리카 추출물 제조 및 추출 수율

적색과 황색 파프리카는 건조기(LD-918BT, LEQUIP, Hwaseong, Korea)를 이용하여 60℃에서 건조하였다. 건조한 적색과 황색 파프리카는 블렌더(HMP-3260S, HANIL ELECTRIC, Seoul, Korea)를 사용하여 분말화하였으며 그 후 증류수에 각각 10배수씩 가하여 autoclave(HB-506-4, HANBAEK SCIENTIFIC CO., Bucheon, Korea)를 이용해 121℃에서 20 min 동안 열수 추출하였다. 그 후 Whatman No.1 여과지로 여과시킨 후 동결건조(PVTD-10R, Ilshinbioase, Dongducheon, Korea)하여 —20℃에서 실험을 진행할 때까지 보관하였다. 증류수에 추출한 적색과 황색 파프리카는 WRP(water extract from red colored paprika)와 WYP(water extract from yellow colored paprika)로 명명하였고 추출 수율은 백분율(%)로 표시하였다(Table 1).

3. DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성

WRP와 WYP의 항산화 활성을 확인하는 방법으로 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성을 측정하였다. 용해된 DPPH 용액은 517 nm에서 최대 흡광도를 나타내며 시료의 환원력에 의해서 시료 첨가와 함께 흡광도가 감소한다(Oh JH 등 2004). 에탄올에 용해한 200 μM DPPH 용액 190 μL와 각 농도별 WRP 또는 WYP 10 μL를 96-well plate에 넣어준 후 37℃ incubator에서 30 min 동안 반응시켜 microplate reader(VersaMax; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)를 사용하여 517 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. 이때 대조군은 시료 대신에 시료의 용매를 10 μL 넣어주었다. 실험결과는 3반복 측정치의 평균값으로 표시하였고 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성은 다음 공식으로 계산되었으며 양성 대조군으로는 비타민 C를 사용하였다.

4. Tyrosinase 저해 활성

WRP와 WYP의 미백 활성을 확인하기 위하여 tyrosinase 저해 활성을 측정하였다. 반응액의 총 부피는 300 μL이며, 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer 220 μL, 각 농도별 WRP 또는 WYP 20 μL, 1.5 mM L-tyrosine 40 μL, 그리고 1,500U tyrosinase 20 μL를 첨가하고 37℃ incubator에서 15 min 동안 반응시켰다. 이때 대조군은 시료 대신에 시료의 용매를 20 μL 넣어주었다. 흡광도는 microplate reader(VersaMax; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)를 사용하여 490 nm의 파장에서 측정하였으며 양성대조군으로는 arbutin을 사용하였다. 실험결과는 3반복 측정치의 평균값으로 표시하였고 tyrosinase 저해 활성은 시료를 첨가한 처리군의 흡광도와 첨가하지 않은 대조군의 흡광도 감소율로 나타내었다.

5. 세포 생존율

B16F10 세포의 생존율에 대한 시료의 영향을 확인하기 위해 MTT 시약을 이용하여 세포독성을 조사하였다(Mosmann T 1983). B16F10 세포를 24-well plate에 분주한 후 세포가 100% 이상 차 있는 상태가 될 때까지 37℃에서 5% CO2 조건하에 배양하였으며 하루 뒤 배양액을 제거하고 바꿔준 배지에 WRP와 WYP를 농도별로 처리한 후 같은 조건하에서 다시 한 번 24 hr 동안 배양하였다. 24 hr이 지나면 시료를 처리한 배지를 제거하고 MTT를 PBS에 0.2 mg/mL 되도록 녹인 용액을 배지에 섞어준 후 각 well마다 MTT-DMEM을 0.5 mL씩 분주한 다음 같은 조건하에 30 min 동안 반응시켰다. 그 후 배지를 제거하고 각 well마다 DMSO를 300 μL씩 넣어 생성된 formazan을 녹여준 후 96-well plate에 100 μL씩 분주하여 microplate reader(VersaMax; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)를 이용해 570 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. 실험결과는 3반복 측정치의 평균값으로 표시하였으며 세포 생존율은 아래의 식을 사용하여 계산하였다.

6. B16F10 세포에서의 멜라닌 생합성 억제

B16F10 세포를 사용해 WRP와 WYP의 멜라닌 생합성 억제 효과를 측정하였다. 0.5 mM IBMX를 처리하여 멜라닌 생성을 유도하고 WRP와 WYP를 농도별로 96 hr 동안 처리하였다. 멜라닌 함량을 측정하기 위하여 배지를 제거하고 PBS로 세척한 후, trypsin-EDTA를 200 μL씩 처리하여 세포를 용해시켜 5 min 동안 원심 분리하였다. 상등액을 제거한 후 400 μL 1N NaOH와 10% DMSO에 용해하여 heating block(Dry thermo unit-2BN, TAITEC, Tokyo, Japan)에서 100℃로 10 min 동안 고정하고 450 nm의 파장에서 흡광도를 측정하여 WRP와 WYP의 멜라닌 생합성 억제 효과를 확인하였다. 또한 현미경을 사용하여 B16F10 세포에서 WRP와 WYP의 멜라닌 생합성 억제 정도를 관찰하였다.

7. 통계분석

모든 데이터는 3회 반복 실험한 것이며 모든 실험 결과는 평균±표준편차로 표현하였다. 통계처리는 SPSS software (Ver. 18, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)를 이용하여 분석하였으며 각 그룹 간의 유의성 평가는 일원배치 분산분석(one-way ANOVA)을 이용하였다. 사후 검증은 Duncan’s 및 Student’s t-test 방법을 사용하여 신뢰 수준 * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 및 *** p<0.001로 비교·분석하였다.

결과 및 고찰

1. DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성

DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성은 시료 내 항산화 물질로부터 공여받은 전자나 수소 원자에 의해 환원되면 보라색에서 노란색으로 변색되는 원리로(Fukumoto LR & Mazza G 2000) 이러한 색상의 변화 정도를 사용하여 항산화 활성을 측정하기 때문에 상대적으로 실험이 용이하고 간편하여 널리 사용되고 있다(Choi JS 등 2003; Musialik M & Litwinienko G 2005). 전자공여 활성이 높을수록 라디칼의 공유결합이 증가하는 것이기 때문에 항산화 물질의 전자공여 활성이 높을수록 활성산소종에 의한 손상을 효과적으로 억제한다고 볼 수 있다(Park MJ 등 2022). 파프리카에 다량 함유되어 있는 카로티노이드는 구조 상 특징 중 하나인 이중 결합이 산화 반응을 종결하고 낮은 산소압에서도 과산화물과 자유라디칼로 인해 조직이 손상되는 것을 보호해준다는 연구 결과도 존재하며(Bendich A 1989; Aizawa K 등 2009), 캡산틴 및 캅소르빈은 활성 산소를 제거해주는 능력과 지질의 과산화에 의한 자유라디칼, superoxide 및 nitric oxide 등의 발생 억제에 탁월하다고 보고되었다(Murakami A 등 2000). 또한 파프리카의 주된 성분 중 하나인 비타민 C는 대표적인 항산화제로 세포에 독성을 나타내지 않고 암 예방 효과를 주는 영양소로 인체 내에서 생성되는 자유 라디칼의 위험을 감소시키며 항산화 활성을 가지고 있다고 보고되었다(Shon MY & Park SK 2006).

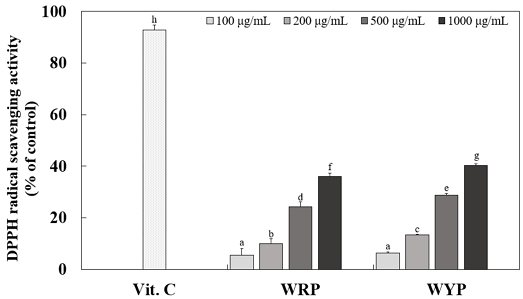

본 연구에서는 WRP와 WYP에 대한 항산화 효과를 측정하기 위하여 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성을 측정하였으며 그 결과는 Fig. 1과 같다. WRP와 WYP를 각각 100, 200, 500 및 1,000 μg/mL의 농도별로 처리하였을 때, 농도가 증가함에 따라 WRP의 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성은 5.46%, 9.92%, 24.23% 및 36.11%로 농도 의존적으로 증가하였으며 WYP 또한 6.33%, 13.40%, 28.71% 및 40.41%로 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성이 농도 의존적으로 증가하는 것을 확인할 수 있었다. 1,000 μg/mL의 농도에서 WRP와 WYP의 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성을 비교했을 때 WRP는 36.11%, WYP는 40.41%로 WYP가 유의적으로 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성이 더 높은 것으로 나타났다. 적색 파프리카의 경우 캡산틴 및 캅소르빈 등과 같은 카로티노이드계 색소가 다량 함유되어 있고 황색 파프리카의 경우 루테인, 제아잔틴 및 β-카로틴 등이 다량 함유되어 있어(Marin A 등 2004; Jeong CH 등 2006; Kim JS 등 2011) 과산화물 생성을 억제할 수 있으며 비교적 천천히 분해되기 때문에 라디칼 소거 효과를 더 길게 나타낼 수 있어 좋은 항산화 물질로 보고된 바 있다(Matsufuji H 등 1998). 이러한 결과는 WRP와 WYP가 농도 의존적으로 DPPH 라디칼을 소거함으로써 WRP와 WYP는 라디칼 소거를 통해 산화적 스트레스를 감소시킬 수 있는 천연 항산화 소재로 사용될 수 있는 가능성을 보여준다.

The antioxidant activities of WRP and WYP against DPPH radical scavenging.Vit. C was used as a positive control. The between 100 and 1,000 μg/mL of WRP and WYP treatment dose-dependently scavenged DPPH radicals. Values represent the mean±S.D. of three independent measurements. Means with different letters (a∼h) above the bars are significantly different by Duncan’s multiple range test (p<0.05). WRP: Water extract from red colored paprika.WYP: Water extract from yellow colored paprika.

2. Tyrosinase 저해 활성

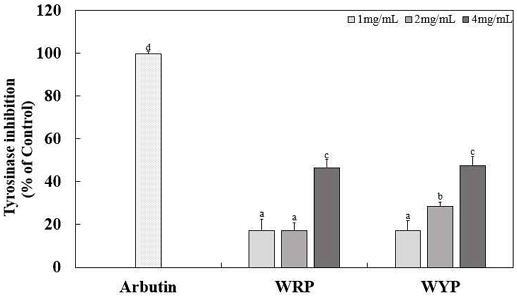

미백과 관련된 연구에는 tyrosinase 활성 억제 및 저해, dihydroxyphenylalanine(DOPA) 산화 억제, 각질층 박리 촉진 및 자외선 차단 등이 있다(Jeong SH 2018). Tyrosinase는 멜라닌 합성에 가장 핵심적인 역할을 하는 단백질로서 멜라닌 합성 억제 기전이 가장 많이 밝혀져 있다(Ando H 등 2007; Chang TS 2009). Tyrosinase는 멜라닌 생합성 과정의 key enzyme으로 melanocyte 내의 melanosome에서 연속적인 산화 반응을 일으켜 멜라닌을 생성한다(Wang KH 등 2006). 멜라닌이 과도하게 생성될 경우 기미, 주근깨, 검버섯, 피부 노화 및 피부암 유발 등의 문제를 야기할 수 있으며 식품의 갈변화를 일으키는 원인이 될 수 있고, tyrosinase 효소 활성을 저해하거나 중간체들의 산화 반응을 저해함으로서 멜라닌 색소가 감소되기에 이와 관련한 검증 방법으로 tyrosinase 활성 저해 연구가 진행되고 있다(Wang KH 등 2006; Lee YS 등 2007; Chang MI 2013). 현재 tyrosinase 저해제가 미백에 관련된 화장품이나 의약품 생산의 증가에 중요한 역할을 하고 있다고 알려져 있으며(Kang HS 등 2004), 지금까지 알려진 tyrosinase 저해제는 비타민 C, arbutin, 벤조산 그리고 아젤라산 등이 있고 그중에서도 본 실험에서도 쓰인 arbutin은 미백 상용제로 널리 쓰이고 있지만 피부 안전성, 제형 안정성 및 경제성 등의 문제로 제한된 양만 사용되고 있기에(Lee HJ 등 2006) 천연물 유래의 tyrosinase 저해제 탐색에 대한 연구가 필요하다고 여겨진다. WRP와 WYP의 미백 효과를 확인하기 위하여 1, 2 및 4 mg/mL의 다양한 농도로 기질인 L-tyrosine을 이용해 tyrosinase 저해 활성을 측정한 결과는 Fig. 2와 같다. 대조군으로 사용한 arbutin은 1 mg/mL의 농도에서 99.78%로 높은 tyrosinase 저해 활성을 보였다. WRP는 17.11%, 17.27% 및 46.54%의 저해 활성을 나타내었으며, WYP는 17.29%, 28.32% 및 47.52%로 대조군에 비해 비교적 낮은 저해 활성을 나타내었지만 농도 의존적으로 tyrosinase를 저해하는 것을 확인할 수 있었다. 4 mg/mL의 농도에서 WRP와 WYP의 tyrosinase 저해 활성을 비교했을 때 WRP는 46.54%, WYP는 47.52%로 WRP와 WYP는 유의적으로 차이가 없었다. 파프리카에는 식물화합물의 대표적 물질인 페놀류, 카로티노이드 그리고 비타민 C 등이 다량 함유되었다고 알려져 있다(Marin A 등 2004; Deepa N 등 2006; Kim JS 등 2011; Chávez-Mendoza C 등 2015). 페놀류의 함량이 높을수록 tyrosinase 저해 효과가 높으며 식물의 여러 페놀류가 tyrosinase 저해 활성이 있다고 보고된 바 있다(Stirpe F & Corte ED 1969; Boissy RE & Manga P 2004). 이를 바탕으로 본 연구 결과는 WRP와 WYP에도 tyrosinase 저해 활성에 영향을 미치는 일정량의 페놀류가 함유되어 있다고 볼 수 있다.

The tyrosinase inhibitory effects of WRP and WYP in vitro.Arbutin was used as a positive control. Tyrosinase inhibition activity was determined in a cell-free, in vitro assay using L-tyrosine as a substrate. Values represent the mean±S.D. of three independent measurements. Means with different letters (a∼d) above the bars are significantly different by Duncan’s multiple range test (p<0.05).WRP: Water extract from red colored paprika.WYP: Water extract from yellow colored paprika.

3. 세포 생존율

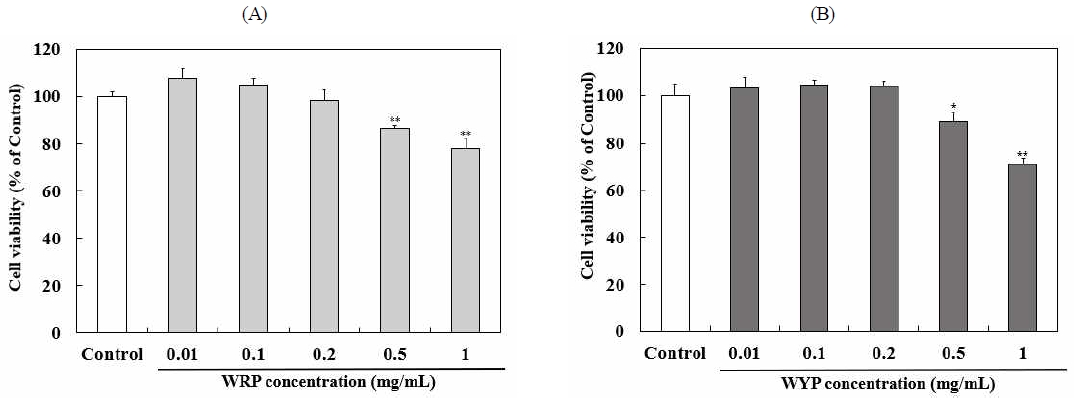

B16F10 세포에서 세포독성을 확인하기 위해 MTT assay를 실행하여 세포 생존율을 측정한 결과는 Fig. 3에 나타내었다. MTT assay는 세포 생존율을 측정하는 대표적인 방법으로 MTT 시약이 세포 내로 흡수된 후 미토콘드리아의 succinate dehydrogenase에 의해 formazan을 형성하며 이물질의 세포 내 축적은 미토콘드리아의 활성 넓게는 세포의 활성을 의미한다. 또한 MTT assay는 세포 증식과 생존력의 in vitro 분석에 매우 유용하게 사용되고 있다(Mosmann T 1983). WRP와 WYP 모두 0.01, 0.1 및 0.2 mg/mL로 처리하였을 때 세포 생존율은 98% 이상으로 대조군의 세포생존율을 100%로 비교하더라도 유의적인 차이가 보이지 않았지만 0.5와 1 mg/mL로 농도로 처리한 결과, 세포 독성으로 인해 두 추출물 모두 70%까지 급격하게 세포 생존율이 저하되는 것을 확인할 수 있었다. 따라서 0.2 mg/mL 농도 이하를 적정 농도로 판단하여 추후 실험에는 유의적인 차이가 나지 않는 농도 2가지 0.1과 0.2 mg/mL만 선택하여 멜라닌 합성 저해 실험을 진행하였다.

Effects of WRP (A) and WYP (B) treatment on the cell viability of B16F10 cells using the MTT assay.B16F10 cells were incubated with 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mg/mL for 24 h. Subsequent experiments were progressed within the concentration range of cell viability higher than 80%. Different corresponding letters indicate significant differences by t-test (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01).Control: 0.5 mM IBMX treatment only.WRP: Water extract from red colored paprika.WYP: Water extract from yellow colored paprika.

4. B16F10 세포에서의 멜라닌 생합성 억제

멜라닌 생성은 tyrosinase에 의한 산화반응뿐만 아니라 여러 종류의 사이토카인, 성장 인자, α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, 부신피질자극호르몬, β-endorphin 등의 호르몬과 여러 종류의 세포신호전달 경로가 관여하는 복잡한 연쇄반응을 거쳐서 생성된다고 알려져 있다(Gaggioli C 등 2003). 그렇기에 피부미백에 효과적인 미백제 개발은 melanocyte 내에서의 멜라닌 생성 억제, melanocyte 자극 물질 조절 및 멜라닌 배설을 촉진시키는 것 이렇게 3가지 방향으로 이루어지고 있다(Mo JH & Oh SJ 2013). 실험에서 사용한 IBMX는 phosphodiesterase를 억제하여 cyclic adenosine monophosphate(cAMP) 활성을 증가시키며 이렇게 활성화 된 cAMP는 extracellular-signal-regulated kinase(ERK)와 phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B(PI3K/PKB) 신호 경로를 인산화시켜 microphthalmia-associated transcription factor(MITF)의 활성화를 유도한다고 보고되어 있다(Byun EB 등 2017). MITF는 멜라닌 합성 과정의 핵심효소인 tyrosinase, tyrosinase-related protein 1(TRP1) 및 dopachrome tautomerase(DCT)에 대한 전사인자로 작용하여 이들의 발현 증가를 유도한다(Kameyama K 등 1995). 이를 토대로 MITF 단백질 분해를 유도한다면 MITF 활성이 저해되어 멜라닌 생성 관련 주요 효소들의 발현 또한 억제될 수 있다는 것을 알 수 있다. 또한 활성산소종 중 피부 광 손상의 중요한 인자인 초과산화음이온 및 하이드록실라디칼은 피부에 존재하는 결합조직 성분인 collagen과 elastin 및 hyaluronic acid 등의 결합사슬 절단 및 비정상적인 교차 결합에 의한 주름 생성과 멜라닌 생성 촉진 등 피부 노화를 가속시키기에 이와 관련하여 천연 물질에 대한 항산화 활성과 미백 기능을 동시에 보고한 경우가 많다(Kim SH 등 2011). 하지만 파프리카의 생리활성 성분을 토대로 한 미백 효과와 관련한 연구는 미비하여 이에 관한 연구가 필요하다고 판단된다.

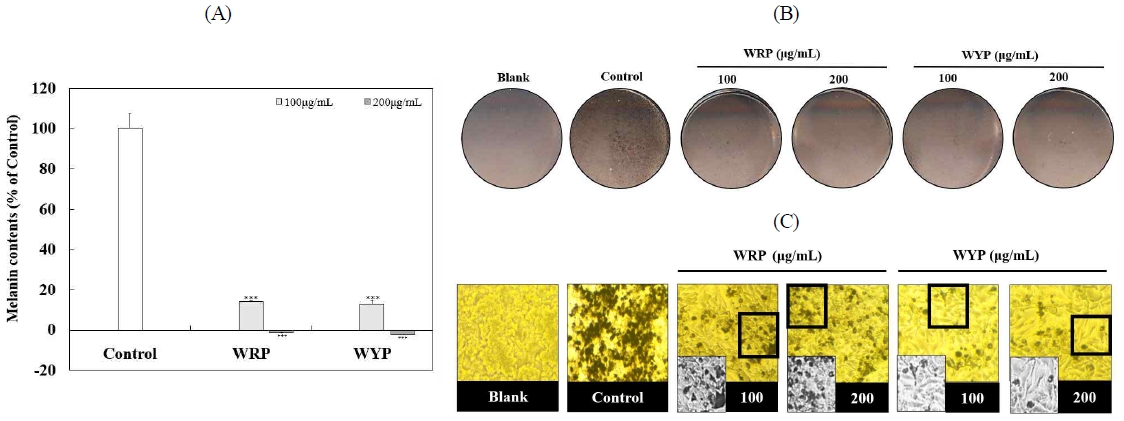

IBMX를 통해 멜라닌 생성을 유도한 B16F10 세포에서의 WRP와 WYP의 멜라닌 형성 억제작용에 대한 결과는 Fig. 4에 나타내었다. 멜라닌 형성 억제 효과를 정량화 한 그래프는 (A)에 나타내었으며 멜라닌 함량 수준을 이미지 스캐너로 스캔한 결과와 현미경으로 분석한 결과는 각각 (B)와 (C)에 나타내었다. WRP와 WYP 모두 100과 200 μg/mL에서 각각 14.17%와 —1.24% 그리고 12.69%와 —2.21%로 농도 의존적으로 멜라닌 생성을 억제하는 것을 확인할 수 있었으며 WRP와 WYP의 멜라닌 생성 억제 효과를 비교했을 때 WRP와 WYP는 유의적으로 차이가 없었다. 또한 MTT assay를 선행 실시하여 B16F10 세포 내에서 세포 독성을 나타내지 않는 농도를 선택하여서 진행하였기 때문에 멜라닌 생성 억제는 추출물 자체가 멜라닌 생합성 과정을 직접적으로 억제하여 생성량을 감소시키는 것으로 볼 수 있다.

Inhibitory effects of WRP and WYP treatment on the IBMX-induced B16F10 melanogenic.Intracellular melanin contents of B16F10 cells were quantified at 450 nm (A). Extracellular melanin levels were obtained using image scanner (B). The levels of melanin content of B16F10 in the of WRP and WYP treatment were analyzed by photomicrographed method (C). Different corresponding letters indicate significant differences by t-test (*** p<0.001).Control: 0.5 mM IBMX.WRP: Water extract from red colored paprika.WYP: Water extract from yellow colored paprika.

요 약

본 연구에서는 적색과 황색 파프리카 추출물을 제조하고 기능성 미용식품 소재로의 활용 가능성을 탐색하였다. WRP와 WYP의 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성은 1,000 μg/mL 농도에서 양성대조군인 비타민 C와 비교하였을 때 각각 36.11%와 40.41%의 소거 활성을 나타내었다. 또한 WRP와 WYP 모두 농도 의존적으로 항산화 활성을 가지고 있음을 확인하였다. 또한 WRP와 WYP의 미백 효과를 확인하고자 tyrosinase 저해 활성을 확인한 결과, WRP와 WYP의 농도가 1, 2 및 4 mg/mL로 농도가 증가할수록 모두 농도 의존적으로 tyrosinase를 저해하고 있음을 확인하였으며 WRP와 WYP가 멜라닌 생성 세포인 B16F10 세포에서도 세포 독성이 없는 최대 농도인 0.2 mg/mL에서 대조군과 비교하였을 때 각각 —1.24%와 2.21%로 멜라닌 생합성을 억제하고 있다는 것을 확인하였다. 위의 결과를 보아 파프리카는 천연 소재로서 라디칼 소거, tyrosinase 저해 활성 및 멜라닌 생합성 억제를 통하여 항산화 활성과 미백 효과를 가지는 것으로 사료되며 더 나아가 이를 바탕으로 한 항산화 활성 및 미백 효과가 뛰어난 천연 소재로서의 활용 가능성이 기대된다.

References

-

Aguirrezábal MM, Mateo J, Domínguez MC, Zumalacárregui JM (2000) The effect of paprika, garlic and salt on rancidity in dry sausages. Meat Sci 54(1): 77-81.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0309-1740(99)00074-1]

-

Aizawa K, Inakuma T (2009) Dietary capsanthin, the main carotenoid in paprika (Capsicum annuum), alters plasma high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels and hepatic gene expression in rats. Br J Nutr 102(12): 1760-1766.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114509991309]

-

Aizawa K, Matsumoto T, Inakuma T, Ishijima T, Nakai Y, Abe K, Amano F (2009) Administration of tomato and paprika beverages modifies hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism in mice: A DNA microarray analysis. J Agric Food Chem 57(22): 10964-10971.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf902401u]

-

Ando H, Kondoh H, Ichihashi M, Hearing VH (2007) Approaches to identify inhibitors of melanin biosynthesis via the quality control of tyrosinase. J Invest Dermatol 127(4): 751-761.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700683]

-

Bendich A (1989) Symposium conclusions: Biological actions of carotenoids. J Nutr 119(1): 135-136.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/119.1.135]

-

Boissy RE, Manga P (2004) On the etiology of contact/occupational vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res 17(3): 208-214.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00130.x]

-

Byun EB, Song HT, Mushtaq S, Kim HM, Kang JA, Yang MS, Sung NY, Jang BS, Byun EH (2017) Gamma-irradiated luteolin inhibits 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine-induced melanogenesis through the regulation of CREB/MITF, PI3K/Akt, and ERK pathways in B16BL6 melanoma cells. J Med Food 20(8): 812-819.

[https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2016.3890]

-

Chang MI, Kim JY, Kim US, Baek SH (2013) Antioxidant, tyrosinase inhibitory, and anti-proliferative activities of Gochujang added with Chenoggukjang powder made from sword bean. Korean J Food Sci Technol 45(2): 221-226.

[https://doi.org/10.9721/KJFST.2013.45.2.221]

-

Chang TS (2009) An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci 10(6): 2440-2475.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms10062440]

-

Chávez-Mendoza C, Sanchez E, Muñoz-Marquez E, Sida-Arreola JP, Flores-Cordova MA (2015) Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in different grafted varieties of bell pepper. Antioxidants 4(2): 427-446.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox4020427]

- Choi JS, Oh JI, Hwang IT, Kim SE, Chun JC, Lee BH, Kim JS, Kim TJ, Cho KY (2003) Application and high throughput screening of DPPH free radical scavenging activity by using 96-well plate. Korean J Pestic Sci 7(2): 92-99.

-

Choi SN, Chung NY (2015) Quality and sensory characteristics of cashew dressing added with paprika juice. J Korean Diet Assoc 21(1): 1-10.

[https://doi.org/10.14373/JKDA.2015.21.1.1]

-

Craft NE, Wise SA, Soares JH (1993) Individual carotenoid content of SRM 1548 total diet and influence of storage temperatur, lyophilization, and irradiation on dietary carotenoids. J Agric Food Chem 41(2): 208-213.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00026a012]

-

Deepa N, Kaur C, Singh B, Kapoor HC (2006) Antioxidant activity in some red sweet pepper cultivars. J Food Compost Anal 19(6-7): 572-578.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2005.03.005]

-

Deli J, Molnár P, Matus Z, Tóth G (2001) Carotenoid composition in the fruits of red paprika (Capsicum annuum var. lycopersiciforme rubrum) during ripening: Biosynthesis of carotenoids in red paprika. J Agric Food Chem 49(3): 1517-1523.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf000958d]

-

Dwyer JH, Navab M, Dwyer KM, Hassan K, Sun P, Shircore A, Hema-Levy S, Hough G, Wang X, Drake T, Merz CN, Fogelman AM (2001) Oxygenated carotenoid lutein and progression of early atherosclerosis: The Los Angeles atherosclerosis study. Circulation 103(24): 2922-2927.

[https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.103.24.2922]

-

Eberlein-König B, Placzek M, Przybilla B (1998) Protective effect against sunburn of combined systemic ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and d-alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E). J Am Acad Dermatol 38(1): 45-48.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70537-7]

-

Eriksson CE, Na A (1996) Antioxidant agents in raw materials and processed foods. Biochem Soc Symp 61: 221-234.

[https://doi.org/10.1042/bss0610221]

-

Fernández-Sevilla JM, Acién Fernández FG, Molina Grima E (2010) Biotechnological production of lutein and its applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 86(1): 27-40.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-009-2420-y]

-

Francisco José Delgado, José González-Crespo, Ramón Cava, Rosario Ramírez (2011) Effect of high-pressure treatment on the volatile profile of a mature raw goat milk cheese with paprika on rind. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 12(2): 98-103.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2011.01.001]

-

Fukumoto LR, Mazza G (2000) Assessing antioxidant and prooxidant activities of phenolic compounds. J Agric Food Chem 48(8): 3597-3604.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf000220w]

-

Gaggioli C, Buscà R, Abbe P, Ortonne JP, Ballotti R (2003) Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) is required but is not sufficient to induce the expression of melanogenic genes. Pigment Cell Res 16(4): 374-382.

[https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00057.x]

- Han YS, Jung ES (2003) A study of correlation between antioxidant activity and whitening effect of plant extracts. Asian J Beauty Cosmetol 1(1): 11-22.

-

Hunter DJ, Willett WC (1994) Diet, body build, and breast cancer. Annu Rev Nutr 14: 393-418.

[https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nu.14.070194.002141]

- Hwang JH, Jang MS (2001) Effect of paprika (Capsicum annuum L.) juice on the acceptability and quality of wet noodle(I). Korean J Food Cook Sci 17(4): 373-379.

- Jeong CH, Ko WH, Cho JR, Ahn CG, Shim KH (2006) Chemical components of Korean paprika according to cultivars. Food Sci Preserv 13(1): 43-49.

-

Jeong SH (2018) A review of current research on natural skin whitening products. Asian J Beauty Cosmetol 16(4): 599-607.

[https://doi.org/10.20402/ajbc.2018.0243]

-

Joshipura KJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Speizer FE, Colditz G, Ascherio A, Rosner B, Spiegelman D, Willett WC (2001) The effect of fruit and vegetable intake on risk for coronary heart disease. Ann Intern Med 134(12): 1106-1114.

[https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00010]

-

Jung JY, Choi MH, Hwang JH, Chung HJ (2004) Quality characteristics of Jeung-pyun prepared with paprika juice. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 33(5): 869-874.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2004.33.5.869]

-

Kameyama K, Sakai C, Kuge S, Nishiyama S, Tomita Y, Ito S, Wakamatsu K, Hearing VJ (1995) The expression of tyrosinase, tyrosinae-related proteins 1 and 2 (TRP1 and TRP2), the silver protein, and a melanogenic inhibitor in human melanoma cells of differing melanogenic activities. Pigment Cell Res 8(2): 97-104.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0749.1995.tb00648.x]

-

Kander MC, Cui Y, Liu Z (2017) Gender difference in oxidative stress: A new look at the mechanisms for cardiovascular diseases. J Cell Mol Med 21(5): 1024-1032.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13038]

- Kang HS, Kim HR, Byun DS, Park HJ, Choi JS (2004) Rosmarinic acid as a tyrosinase inhibitors from Salvia miltiorrhiza. Nat Prod Sci 10(2): 80-84.

- Kim HJ, Jhon DY (2001) Characteristics of Kimchi containing paprika instead of hot pepper. Food Sci Biotechnol 10(3): 241-245.

-

Kim JS, Ahn JY, Lee SJ, Moon BK, Ha TY, Kim SN (2011) Phytochemicals and antioxidant activity of fruits and leaves of paprika (Capsicum annuum L., var. Special) cultivated in Korea. J Food Sci 76(2): 193-198.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01891.x]

-

Kim SH, Lee SY, Hong CY, Gwak KS, Yeo HM, Lee JJ, Choi IG (2011) Whitening and antioxidant activities of essential oils from Cryptomeria japonica and Chamaecyparis obtusa. J Korean Wood Sci Technol 39(4): 291-302.

[https://doi.org/10.5658/WOOD.2011.39.4.291]

- Ko WH (2005) Physicochemical properties and application of different Korean paprika varieties. MS Thesis Gyeongsang National University, Jinju. pp 1-2.

-

Lee HJ, Lee MK, Park IS (2006) Characterization of mushroom tyrosinase inhibitor in sweet potato. J Life Sci 16(3): 396-399.

[https://doi.org/10.5352/JLS.2006.16.3.396]

-

Lee KY, Han CY, Pyo MJ, Choi SG (2022) Effect of red paprika powder on quality and oxidative stability of mayonnaise prepared with perilla oil. Food Sci Preserv 29(6): 932-942.

[https://doi.org/10.11002/kjfp.2022.29.6.932]

-

Lee YS, Choi JB, Joo EY, Kim NW (2007) Antioxidative activities and tyrosinase inhibition of water extracts from Ailanthus altissima. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 36(9): 1113-1119.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2007.36.9.1113]

-

Liu RH (2003) Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. Am J Clin Nutr 78(3): 517S-520S.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/78.3.517S]

-

Loft S, Astrup A, Buemann B, Poulsen HE (1994) Oxidative DNA damage correlates with oxygen consumption in humans. FASEB J 8(8): 534-537.

[https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.8.8.8181672]

-

Marín A, Ferreres F, Tomás-Barberán FA, Gil MI (2004) Characterization and quantitation of antioxidant constituents of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). J Agric Food Chem 52(12): 3861-3869.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0497915]

-

Matsufuji H, Nakamura H, Chino M, Takeda M (1998) Antioxidant activity of capsanthin and the fatty acid esters in paprika (Capsicum annuum). J Agric Food Chem 46(9): 3468-3472.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf980200i]

- Mo JH, Oh SJ (2013) Tyrosinase inhibitory activity and melanin production inhibitory activity of the methanol extract and fractions from Dendropanax morbifera Lev. Korean J Aesthet Cosmetol 11(2): 275-280.

-

Mosmann T (1983) Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 65(1-2): 55-63.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4]

-

Murakami A, Nakashima M, Koshiba T, Maoka T, Nishino H, Yano M, Sumida T, Kim OK, Koshimizu K, Ohigashi H (2000) Modifying effects of carotenoids on superoxide and nitric oxide generation from stimulated leukocytes. Cancer Lett 149(1-2): 115-123.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3835(99)00351-1]

-

Musialik M, Litwinienko G (2005) Scavenging of DPPH radicals by vitamin E is accelerated by its partial ionization: The role of sequential proton loss electron transfer. Org Lett 7(22): 4951-4954.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/ol051962j]

-

Oh JH, Kim EH, Kim JL, Moon YI, Kang YH, Kang JS (2004) Study on antioxidant potency of green tea by DPPH Method. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 33(7): 1079-1084.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2004.33.7.1079]

- Park MJ, Kim HS, Kim HB, Lee SG, Cho SJ (2022) Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of extracts from different parts of Sophora japonica L. J Life Sci 32(10): 792-802.

-

Park YJ, Jo YH, Kwon JH (2017) Effects of quarantine doses of e-beam irradiation on the physicochemical and sensory characteristics of paprika. Korean J Food Sci Technol 49(2): 117-122.

[https://doi.org/10.9721/KJFST.2017.49.2.117]

-

Pitchumoni SS, Doraiswamy PM (1998) Current status of antioxidant therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 46(12): 1566-1572.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01544.x]

-

Poojary MM, Barba FJ, Aliakbarian B, Donsì F, Pataro G, Dias DA, Juliano P (2016) Innovative alternative technologies to extract carotenoids from microalgae and seaweeds. Mar Drugs 14(11): 214.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/md14110214]

-

Poprac P, Jomova K, Simunkova M, Kollar V, Rhodes CJ, Valko M (2017) Targeting free radicals in oxidative stress-related human diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci 38(7): 592-607.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2017.04.005]

-

Seddon JM, Ajani UA, Sperduto RD, Hiller R, Blair N, Burton TC, Farber MD, Gragoudas ES, Haller J, Miller DT, Yannuzi LA, Willet W (1994) Dietary carotenoids, vitamins A, C, and E, and advanced age-related macular degeneration. J Am Med Assoc 272(18): 1413-1420.

[https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1994.03520180037032]

- Shon MY, Park SK (2006) Synergistic effect of Yuza (Citrus junos) extracts and ascorbic acid on antiproliferation of human cancer cells and antioxidant activity. Food Sci Preserv 13(5): 649-654.

-

Sliveria ER, Moreno FS (1998) Natural retinoids and β-carotene: From food to their actions on gene expression. J Nutr Biochem 9(8): 446-456.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-2863(98)00040-0]

-

Steinmetz KA, Poter JD (1996) Vegetables, fruit and cancer prevention: A review. J Am Diet Assoc 96(10): 1027-1039.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00273-8]

-

Stirpe F, Corte ED (1969) The regulation of rat liver xanthine oxidase: Conversion in vitro of the enzyme activity from dehydrogenase (Type D) to oxidase (Type O). J Biol Chem 244(14): 3855-3861.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(17)36428-1]

-

Tobin D, Thody AJ (1994) The superoxide anion may mediate short but not long term effects of ultraviolet radiation on melanogenesis. Exp Dermatol 3(3): 99-105.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0625.1994.tb00266.x]

- Vatassery GT (1998) Vitamin E and other endogenous antioxidants in the central nervous system. Geriatrics 53(1): S25-S27.

-

Wang KH, Lin RD, Hsu FL, Huang YH, Chang HC, Huang CY (2006) Cosmetic applications of selected traditional Chinese herbal medicines. J Ethnopharmacol 106(3): 353-359.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2006.01.010]