대두 에탄올 추출물(Glycine max (L.) Merr)의 항산화 효과 및 Tyrosinase 저해 활성

1경남대학교 대학원 건강과학과 석사과정2경남대학교 제약공학과 교수

2Professor, Dept. of Pharmaceutical Engineering, Kyungnam University, Changwon 51767, Republic of Korea

Abstract

Soybeans (Glycine max (L.) Merr) are known for their nutritional value as they are, rich in protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. In this study, the ethanol extract (GEE) of Glycine max (L.) Merr was prepared and its potential antioxidant and skin whitening effects were investigated. The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity and reduction potential were evaluated to assess the antioxidant capabilities and total phenolic content of GEE. Additionally, a tyrosinase inhibition assay was conducted to assess its potential for promoting skin whitening. GEE was found to have a total phenolic content of 6.09 μg GAE/mL at 800 μg/mL concentration, confirming its significant antioxidant capability. Moreover, GEE exhibited robust antioxidant potential with DPPH radical scavenging activity reaching 40.24% and a reduction power of 20.82% at 800 μg/mL concentration, demonstrating a concentration-dependent increase. However, the ability of GEE to inhibit tyrosinase was lower compared to the positive control arbutin. Further, GEE did not display concentration-dependent tyrosinase inhibition and skin whitening effects. Therefore, these results suggest that the antioxidant attributes of soybeans, with their diverse physiological benefits, could position them as a promising ingredient in health-functional foods.

Keywords:

Glycine max (L.) Merr, soybean, antioxidant, whitening, functional foods서 론

대두(Glycine max (L.) Merr)는 식물성 단백질과 지방의 주요 공급원으로써 중요한 작물이다(Sedivy EJ 등 2017). 대두는 전 세계적으로 생산량이 매년 꾸준히 증가하고 있으며(Liu K 2000), 단백질과 같은 1차 대사산물 외에도 항산화활성, 항암 활성 그리고 면역력 증강 등의 생리활성을 가진 2차 대사산물을 다양하게 함유하고 있다고 알려져 있다(Coward L 등 1993). 이러한 영양학적 우수성 이외에도 대두는 다양한 생리활성이 보고되고 있는데, 이는 식이섬유, 올리고당, phytic acid, Bowman-Brik protease inhibitor, 이소플라본, 사포닌, 레시틴, 가수분해 펩타이드, 식물성 sterol 그리고 페놀 화합물 등에 기인하는 것으로 밝혀졌으며, 기능성 식품 소재로서 관심과 연구의 대상이 되어왔다(Kim SR 등 1999, 2004). 대두의 genistien은 주로 피부에서 항산화와 항암효과를 지니고 있는 것으로 보고된 바 있으며(Afaq F & Mukhtar H 2006), 쥐와 사람에서 자외선에 의한 피부암과 광손상을 억제하는 것으로 나타났다(Wei H 등 1993, 2002). 또한 대두에는 토코페롤과 같은 천연 항산화제가 함유되어 있어 저장 및 가공 과정 중 산화안정성에 기여하는 것으로 밝혀졌으며, 생체 내에서는 활성 산소를 소거시켜 유리기와 과산화 지질의 생성을 억제하는 항산화 작용을 한다고 보고된 바 있다(Barnes PJ 1983).

활성 산소종(reactive oxygen species; ROS)은 일반적인 산소 분자보다 반응성이 높은 분자들로 대표적으로는 O2-(superoxide anion), H2O2(hydrogen peroxide), OH-(hydroxyl radical) 그리고 1O2(singlet oxygen) 등이 있다(Thannickal VJ & Fanburg BL 2000). 활성 산소종은 건강한 상태에서도 일정량 생체에서 생성되나, 허혈 자체 또는 재관류 시 산소의 재공급으로 인하여 대량으로 생성되어 체내의 정상적인 항산화제 체계로는 환원이 안 되기 때문에 결국 재관류로 인한 조직의 손상을 초래하는 것으로 알려져 있다(Wilson JX & Gelb AW 2002). 이러한 원인 물질인 활성 산소나 유리라디칼을 제거함으로서 노화와 산화작용이 원인으로 발생하는 각종 질환을 예방하고자 항산화제에 대한 연구가 더욱 활발히 진행되고 있다(Valko M 등 2007).

합성 항산화제는 오랜 기간 복용할 경우 간, 신장, 위장 그리고 순환계의 기능에 영향을 미칠 수 있으며, 암 발생과도 연관이 있음이 보고된 바 있다(Choe SY & Yang KH 1982). 합성 항산화제에 대한 우려가 커짐에 따라 천연 항산화제에 대한 필요성이 대두되고 있으며(Hyun MR 등 2011), 인간이 오랫동안 섭취해 온 약용식물은 우리 주변에서 쉽게 찾을 수 있을 뿐만 아니라 안전한 천연물로서, 일부 성분들은 체내 항산화 물질로 이용되어 활성 산소로 인한 산화적 스트레스를 방어해 질병을 예방할 수 있는 것으로 보고되어진다(Cho YJ 등 2008). 최근 잘못된 식생활로 인해 각종 만성질환의 발생이 증가함에 따라 항산화 작용과 같은 생리활성을 갖는 식품 및 소재에 대한 관심이 높아지고 있다. 대두와 관련하여 항염 및 항암 활성 등에 대한 연구는 비교적 많이 진행되어 왔지만(Imm JY & Kim SJ 2010; Chung EK 등 2011) 항산화 활성 및 미백 활성 등의 미용기능성 연구는 아직 미비한 실정이다.

따라서 본 연구에서는 기능성 식품 소재로 잠재력을 내재하고 있는 대두를 활용하여 대두 에탄올 추출물을 제조하고 이의 항산화 효과와 tyrosinase 저해 활성을 평가하여 미용 기능성 식품소재로의 가능성에 대한 실험을 실시하였다.

재료 및 방법

1. 실험재료

본 실험에서는 항산화 활성과 미백 활성을 평가하기 위해 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl(DPPH), ascorbic acid, copper(Ⅱ) chloride, neocuproine, sodium carbonate, Folin-Ciocalteu phenol reagent, gallic acid, L-tyrosine, mushroom tyrosinase, arbutin은 Sigma-Aldrich(St. Louis, MO, USA)에서 구매하였으며 dimethyl sulfoxide(DMSO)는 Junsei chemical Co., Ltd.(Tokyo, Japan)에서 구매하였고 94.5% 에탄올은 Daejung(Seoul, Korea)에서 구매하였다.

2. 대두 에탄올 추출물 GEE의 제조

본 연구에서는 대두 에탄올 추출물을 파이토알렉신(Gimhae, Korea)에서 제공받아 사용하였다. 대두 에탄올 추출물을 카트리지 5 μm 폴리프로필렌 필터를 이용하여 여과하였으며 3 h 동안 환류 추출해 동결 건조하였다. 동결 건조한 시료는 —20℃에서 보관하며 이후 실험할 농도로 DMSO에 희석하여 사용하였다. 대두 에탄올 추출물은 GEE(Glycine max (L.) Merr ethanol extract)로 명명하였다.

3. 총 폴리페놀 함량 측정

2 mL 마이크로 튜브에 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 및 800 μg/mL의 농도 시료 200 μL와 증류수를 1,000 μL 넣어주고 50%(v/v) Folin-Ciocalteu phenol reagent(FCP)를 100 μL 첨가한 후, 상온에서 5 min 동안 반응시켜 GEE의 환원력을 확인하였다. FCP는 필요한 양에 따라 증류수와 FCP를 1:1 비율로 계산하여 분주하기 직전 제조하였다. 5 min이 지나고 나면 증류수에 용해시킨 5%(w/v) Na2CO3 용액을 200 μL 첨가하고 어두운 곳에서 1 h 동안 반응시킨 후 96-well plate에 200 μL씩 분주한 뒤 microplate reader(VersaMax; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)를 사용하여 725 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. 표준물질 gallic acid를 이용하여 표준 곡선을 작성하였으며 GEE의 총 페놀 함량은 작성한 표준 곡선수식인 y=0.0376x—0.0224에 대입하여 산출해 μg GAE/mL로 나타내었으며 표준 곡선의 R2값은 R2=0.9982의 결과값을 나타내었다.

4. DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성

대두 에탄올 추출물인 GEE의 항산화 활성을 평가하기 위하여 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성을 측정하였다. 라디칼은 빛과 온도 등 외부 환경에 불안정하므로 94.5% 에탄올에 용해시켜 200 μM의 DPPH 라디칼 용액을 제조한 후 반응 전까지 호일에 감싸 0℃에서 안정화하였다. 96-well plate에 미리 제조해 둔 DPPH 라디칼 용액 190 μL와 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 및 800 μg/mL의 농도 시료를 각각 10 μL씩 넣은 후, 빛을 차단하기 위해 96-well plate 전체에 호일을 씌우고 37℃ incubator에서 30 min 동안 반응시켜 517 nm에서 microplate reader(VersaMax, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)를 사용하여 흡광도를 측정하였다. 시료를 첨가하지 않은 대조군은 시료 대신에 시료의 용매인 DMSO를 10 μL 넣어주었으며 각 시료의 DPPH 라디칼 소거능은 아래의 계산식을 사용하여 백분율로 나타내었다. 또한 양성대조군으로는 대표적인 항산화 물질인 ascorbic acid를 사용하였고 GEE와 같은 농도에서 비교하였다.

5. 환원력

증류수에 CuCl2를 용해시켜 1 mM CuCl2 용액을 제조하고 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer(pH 7.4)에 0.625 mM neocuproine을 용해하여 250 μM neocuproine 용액을 제조하였다. 96-well plate에 미리 제조해 둔 1 mM CuCl2 용액 20 μL와 250 μM neocuproine 용액 80 μL, 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer(pH 7.4) 60 μL 그리고 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 및 800 μg/mL의 농도 시료를 40 μL 넣어주었다. 그 후 실온에서 1 h 동안 반응시켜주고 반응이 끝나면 microplate reader(VersaMax Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)를 사용하여 454 nm의 파장에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. 대조군은 시료 대신에 시료의 용매인 DMSO를 40 μL 첨가해 주었으며 양성 대조군으로는 앞 실험과 동일하게 ascorbic acid를 사용하였다.

6. Tyrosinase 저해 활성

대두 에탄올 추출물인 GEE의 미백 활성을 평가하기 위해 tyrosinase 저해 활성을 분석하였다. 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer에 L-tyrosine을 용해하여 1.5 mM L-tyrosine을 제조한 후 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 및 800 μg/mL 농도의 시료 20 μL에 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer 220 μL, 1.5 mM L-tyrosine 40 μL 그리고 1,500 U mushroom tyrosinase 20 μL를 첨가하여 37℃ incubator에서 15 min 동안 반응시켰다. 그 후 microplate reader(VersaMax, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)를 사용해 490 nm의 파장에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. 시료를 첨가하지 않은 대조군은 시료의 용매인 DMSO를 20 μL 첨가하였으며 또한 양성 대조군으로는 미백 성분으로 잘 알려진 arbutin을 사용하였고 시료와 같은 농도로 진행하였다. Tyrosinase 저해 활성은 GEE나 양성 대조군인 arbutin을 첨가한 첨가군과 무첨가군의 흡광도 감소율로 나타내었다.

7. 통계처리

모든 실험은 3회 반복하였으며, 모든 데이터는 평균±표준편차로 표현하였다. 데이터의 통계처리는 SPSS software(Ver.18, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)를 사용하여 분석하였다. 일원 배치 분산분석(one-way ANOVA)을 통해 그룹 간의 유의성을 평가하였고, 사후검증은 Duncan’s test를 이용하여 신뢰수준 p<0.05에서 각 구간의 유의성 차이를 검증하였다.

결과 및 고찰

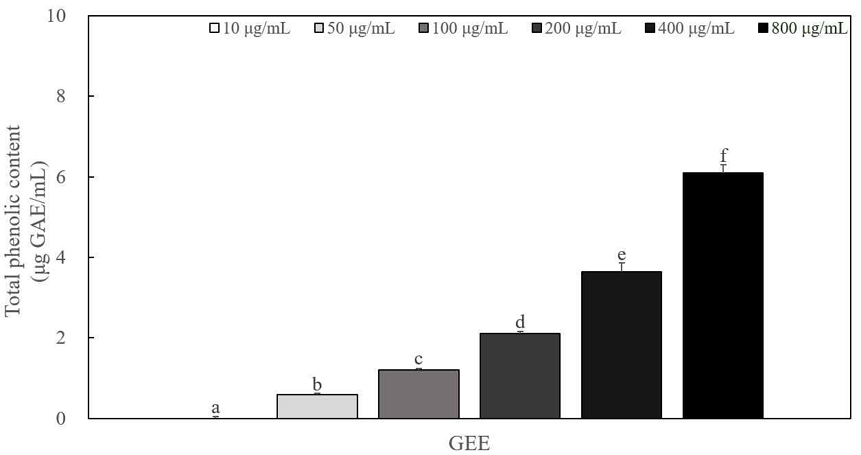

1. 총 폴리페놀 함량 측정

많은 페놀계 물질들은 다양한 생리활성을 가지고 있기 때문에 기능성 식품의 주요 성분으로 주목받고 있다(Whang HJ 등 2001). 페놀 화합물에 존재하는 hydroxyl group은 자유라디칼의 중화시키는 수소이온을 공여하는 능력이 있으며, 폴리페놀의 함량이 증가할수록 항산화력이 증가하는 경향을 보인다(Imai J 등 1994; Halliwell B 등 1995). 이를 통해 총 페놀 함량을 측정하여 추출물의 항산화능을 유추할 수 있다. GEE의 총 폴리페놀 함량을 분석한 결과는 Fig. 1에 나타내었으며 시료의 표준물질인 gallic acid의 양으로 환산하여 나타내었다. GEE는 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 및 800 μg/mL의 농도로 처리하였으며 총 페놀 함량은 0.00, 0.59, 1.20, 2.12, 3.65 및 6.09 μg GAE/mL로 농도 의존적으로 증가하는 것을 확인하였다. 시료의 폴리페놀 함량은 일반적으로 품종, 숙성시기, 껍질의 색 등에 따라 큰 차이를 나타내기도 한다(Rice-Evans CA 등 1997; Díaz-Mula HM 등 2009). 페놀 화합물 함량과 항산화 활성간의 상호작용에 대한 많은 연구들에서 알 수 있듯이 식물체가 지니고 있는 페놀 화합물의 함량을 조사함으로써 천연 추출물의 항산화 활성을 탐색하는 일차적인 자료가 될 수 있을 것으로 판단되며(Boo HO 등 2009), 곡물에 함유된 페놀 성분은 산화방지 능력과 매우 높은 상관성을 가지기 때문에(Lee SC 등 2006; Kanatt SR 등 2011) 본 실험 결과는 GEE의 항산화 활성의 기초 자료로 사용될 수 있을 것으로 사료된다. 대두에 함유된 페놀성 화합물에는 플라보노이드, 이소플라본, 페놀산, 리그난 등이 있다고 보고되어진다(Kurzer MS & Xu X 1997).

The total phenolic content of GEE was calculated as gallic acid equivalent (GAE).The total phenol of GEE was measured at various concentrations (10, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800 μg/mL). The total phenolic content of GEE was increased concentration-dependently. Different corresponding letters indicate significant differences by Duncan’s test (p<0.05).GEE: Glycine max (L.) Merr ethanol extract.

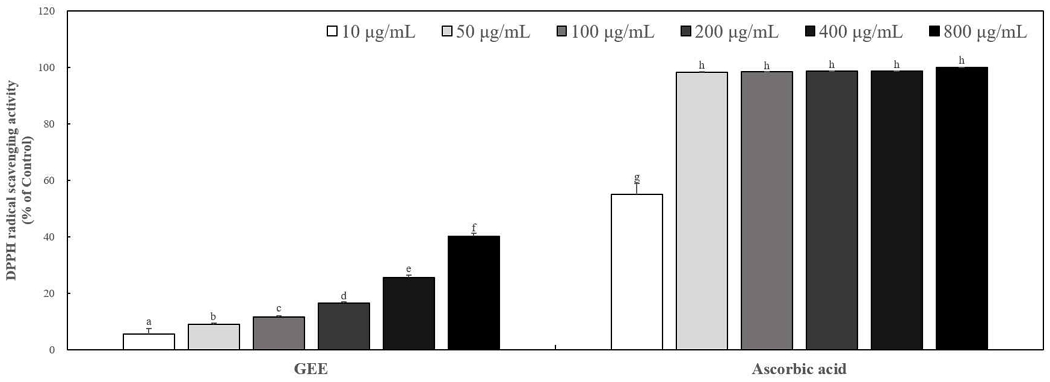

2. DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성

일반적으로 특정 물질에 대한 항산화 활성을 측정하는 방법에는 여러 가지가 있으나 그 중에서 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성법은 비교적 간단하면서도 대량으로 측정이 가능한 방법이다(Choi KM 등 2005). DPPH 라디칼 소거능은 화학적으로 유도되는 organic nitrogen radical로 항산화 활성이 있는 물질과 만나면 매우 빠른 속도로 전자를 공여받아 안정한 화합물인 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazin으로 전환되는데, 이때 짙은 보라색이 엷어지는 특성이 있다(Thongchai W 등 2009). DPPH assay에 따른 free radical 소거능은 안정한 상태의 활성 산소종을 이용하여 항산화력을 검증하는 데 널리 이용하고 있다(Lee MH & Kan SM 2018). 대두 에탄올 추출물 GEE의 항산화 활성을 측정하기 위한 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성 측정 결과는 Fig. 2와 같다. GEE는 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 및 800 μg/mL의 농도로 처리하였고 양성대조군으로는 잘 알려진 항산화제인 ascorbic acid를 이용하여 같은 농도에서 비교하였다. GEE는 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 및 800 μg/mL 각각의 농도에서 5.56%, 8.92%, 11.56%, 16.54%, 25.50% 및 40.24%의 DPPH 라디칼 소거능을 나타내었으며 양성 대조군인 ascorbic acid는 55.02%, 98.27%, 98.41%, 98.58%, 98.59% 및 99.97%의 DPPH 라디칼 소거능을 나타내었다. GEE는 ascorbic acid에 비해서는 비교적 낮은 소거능을 보였지만, 농도 의존적으로 증가하는 것을 확인할 수 있었다. 대두의 여러 가지 생리활성을 설명하는 기작의 하나로 항산화 효과가 거론되고 있으며(Wel H 등 1995; Giles D & Wei H 1997), 대두에서 항산화 효과를 나타내는 것으로 알려진 물질로는 genestein과 daidzein을 포함하는 isoflavones 및 phenolic acids, 토코페롤, 피트산, 트립신 저해제와 아미노산 및 peptide들이 관여하는 것으로 알려져 있으며(Hayes RE 등 1997), 대두에는 이소플라본, 사포닌, 식이섬유, 레시틴 등과 영양물질인 단백질, 지방, 탄수화물 등 생리활성 물질이 많이 함유되어 있기 때문에(Lim JM 등 2020) 항산화 활성과 대두 추출물의 생리활성 성분에 대한 연관성에 대하여 추가적인 분석이 추후 요구된다.

Antioxidant activity of GEE was examined by DPPH radical scavenging assay.Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of GEE and ascorbic acid were evaluated at various concentrations (10, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800 μg/mL). GEE was increased in a concentration-dependent. Different corresponding letters indicate significant differences by Duncan’s test (p<0.05).GEE: Glycine max (L.) Merr ethanol extract.

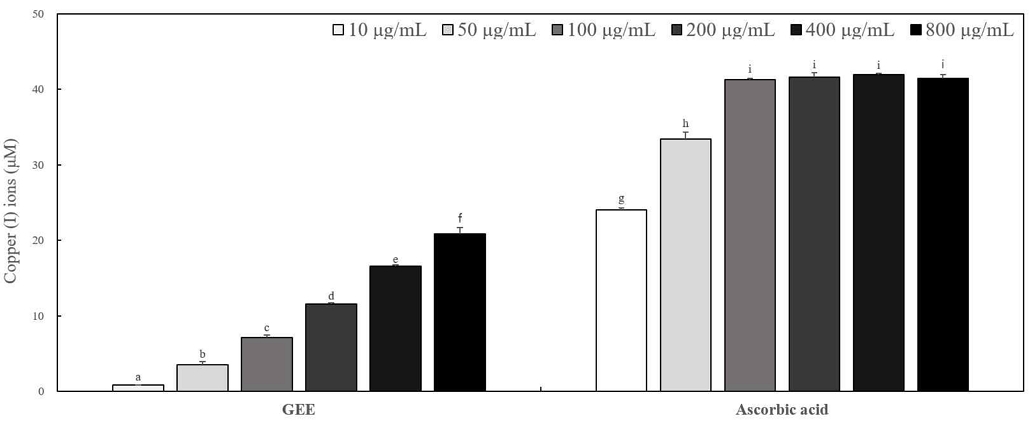

3. 환원력

대두 에탄올 추출물(GEE)의 환원력을 측정하기 위해 copper reduction assay를 실시하였다. 환원력은 다양한 항산화 활성 중 활성산소종과 유리기에 전자를 공여하는 능력이다(Oyaizu M 1986). 환원력에서의 흡광도 수치는 그 자체가 그 시료의 환원력을 나타내며, 높은 환원력을 가지는 물질은 흡광도의 수치가 높게 나타나고(Tanaka M 등 1988), 환원력은 시료가 항산화제로서 사용될 수 있음을 나타내는 지표이기도 하다(Meir S 등 1995). 환원력이 클수록 과산화 지질 및 활성산소를 제거하여 성인병을 예방하는 효과가 있기 때문에 환원력을 유지하는 능력이 클수록 그 이용 가치가 크다(Choi YM 등 2007). GEE의 환원력 측정 결과는 Fig. 3에 나타내었다. GEE의 환원력을 측정한 결과, 농도가 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 및 800 μg/mL로 증가할수록 환원력 역시 0.82, 3.51, 7.15, 11.53, 16.55 및 20.82 μM로 증가하는 것을 확인할 수 있었다. 또한 양성대조군인 ascorbic acid는 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 및 800 μg/mL로 처리하였을 때 23.99, 33.41, 41.26, 41.60, 41.90 및 41.41 μM만큼 Cu2+을 Cu1+로 환원시키는 것을 확인할 수 있었다. Choi SY 등(2006)의 연구를 보면 DPPH radical 소거능과 환원력은 밀접한 관계를 가지고 있으며, 총 폴리페놀 함량이 높을수록 항산화 능이 높은 것을 알 수 있다. 본 실험에서는 대두 에탄올 추출물의 농도가 증가될수록 DPPH 라디칼 소거 활성능이 좋았고 환원력도 같은 경향을 보였으며 이를 통해 항산화 활성이 우수함을 확인하였다. 최근에는 대두의 라디칼 소거활성, 환원력 등의 항산화 활성에 관한 연구도 활발히 진행되고 있으며(Prakash D 등 2007; Xu B & Chang SK 2008; Szymczak G 등 2017), 대두에는 각종 페놀 화합물과 플라보노이드의 일종인 이소플라본이 많이 함유되어 있어 이러한 물질들이 환원력을 나타내는 항산화 활성을 나타낸다고 추정된다(Park JW 등 2007).

Copper reduction activity of GEE.Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. Copper reduction activity of GEE and ascorbic acid were evaluated at various concentrations (10, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800 μg/mL). GEE was confirmed to inhibit copper ions in a concentration-dependently. Different corresponding letters indicate significant differences by Duncan’s test (p<0.05).GEE: Glycine max (L.) Merr ethanol extract.

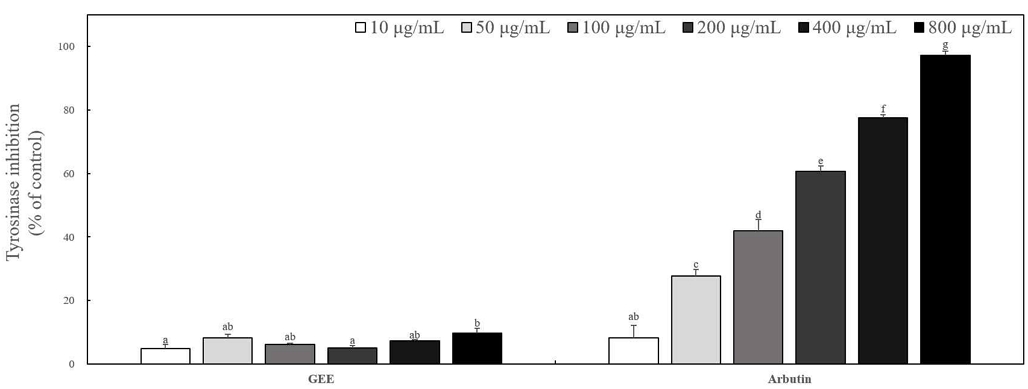

4. Tyrosinase 저해 활성

GEE의 멜라닌 생합성을 조절하는 효소인 tyrosinase의 직접적인 영향을 확인하기 위해 mushroom tyrosinase의 저해 활성능을 측정한 결과는 Fig. 4와 같다. GEE를 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 및 800 μg/mL의 농도로 제조하여 실험하였으며 양성 대조군으로는 미백 물질로 잘 알려진 arbutin을 사용하였다. 실험 결과 GEE는 4.96%, 8.34%, 6.14%, 5.08%, 7.28% 및 9.80%의 tyrosinase 저해능을 보였으며 arbutin은 8.34%, 27.89%, 41.90%, 60.79%, 77.62% 및 97.25%의 tyrosinase 저해능을 보였다. Melanogenesis는 여러 단계의 연속적인 반응을 통하여 멜라닌을 생성하며 tyrosinase가 첫 단계를 진행하는 가장 중요한 역할을 하는 효소로 알려져 있다. Tyrosinase는 polyphenol oxidase라고도 불리며 멜라닌이 생성되는 미생물, 동물 및 식물에 다양하게 분포하고 있다(Kim SH 등 2013). Tyrosinase는 tyrosine을 산화시켜 기질인 L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine(DOPA) 및 DOPA quinone을 만드는 DOPA oxidase로서 작용함과 동시에 DOPA chrome에서 유도된 5,6-dihydroxyindole(DHI)이 indole-5,6-quinone 변환과정에 관여하여 melanin 중합체를 합성하는 데 중요한 효소로 작용한다(Marmol V & Beermann F 1996). 대두는 세포 내 멜라닌 생성을 억제하는데 효과적이며 미백 효과가 우수하다고 보고된 바 있으며(Yoo JK 등 2013), 대두의 생리활성물질 중 하나인 isoflavone의 aglycone 형태인 genistein과 미백 효과의 관계에 대한 연구인 Yang ES 등(2008)은 멜라닌 세포에 genistein을 처리한 후 tyrosinase 활성을 측정한 결과 농도 의존적으로 tyrosinase의 활성이 감소했다고 보고된 바 있다. 또한 대두의 이소플라본 특히 daidzein과 genistein의 미백 기능은 여러 연구에 의해 오래전부터 밝혀진 바 있으며(Paine C 등 2001; Huang ZR 등 2008; Leyden J & Wallo W 2011), 본 실험에서 GEE는 arbutin과 비교하여 현저히 낮은 저해능을 보여 추후 연구에서 세포를 이용한 미백 실험을 진행하여 GEE의 미백 활성을 확인할 필요가 있다고 판단된다.

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity of GEE.The tyrosinase inhibitory activities of GEE was evaluated at various concentrations (10, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800 μg/mL). Arbutin was used as a positive control. The concentration-dependent tyrosinase activity of Arbutin used as a positive control group was suppressed. Different corresponding letters indicate significant differences by Duncan’s test (p<0.05).GEE: Glycine max (L.) Merr ethanol extract.

요 약

본 연구에서는 다양한 생리활성 기능을 가지고 있는 대두의 항산화와 미백 기능을 검증하고자 에탄올로 추출한 대두 에탄올 추출물(GEE)의 항산화 성분(총 페놀함량)을 측정하였고 다양한 in vitro 모델을 사용하여 항산화 활성과 미백 활성을 평가하였다. 항산화 활성은 DPPH 라디칼 소거능과 환원력 이용하였으며 미백 활성은 tyrosinase 저해능을 통해 평가하였다. GEE의 총 페놀 함량은 가장 높은 농도인 800 μg/mL에서 6.09 μg GAE/mL로 항산화 활성을 뒷받침 하는 근거로 사용될 수 있으며, DPPH 라디칼 소거능과 환원력 역시 가장 높은 농도인 800 μg/mL에서 각각 40.24%, 20.82 μM로 높은 항산화 활성을 보였다. 또한 tyrosinase 저해능은 가장 높은 농도인 800 μg/mL에서 9.80%를 나타내었지만 추후 세부적인 미백 실험을 진행할 필요가 있다고 판단된다. 고령화 사회의 도래로 인한 평균 수명 증가로 건강 증진에 대한 높은 관심도를 고려하였을 때, 대두 에탄올 추출물을 통한 실험 결과에 따라 대두는 페놀성 화합물 및 생리활성 물질이 풍부하여 항산화 효과와 미백 기능을 토대로 하는 부작용 없는 천연 항산화제와 미용 기능성 식품소재로서의 활용이 가능할 것으로 기대된다.

References

-

Afaq F, Mukhtar M (2006) Botanical antioxidants in the prevention of photocarcinogenesis and photoaging. Exp Dermatol 15(9): 678-684.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00466.x]

- Barnes PJ (1983) Progress in cereal chemistry and technology. pp 1095-1100. In: Proc. 7th world cereal and bread congress. Holas J, Kratochvil J (eds). Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherland.

- Boo HO, Lee HH, Lee JW, Hwang SJ, Park SU (2009) Different of total phenolics and flavonoids, radical scavenging activites and nitrite scanvenging effects of Momordica charantia L. according to cultivars. Korea J Med Crop Sci 17(1): 15-20.

-

Cho YJ, Ju IS, Chun SS, An BJ, Kim JH, Kim MU, Kwon OJ (2008) Screening of biological activities of extracts from Rhododendron mucronulatum Turcz. flowers. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 37(3): 276-281.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2008.37.3.276]

- Choe SY, Yang KH (1982) Toxicological studies of antioxidants, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA). Korean J Food Sci Technol 14(3): 283-288.

- Choi KM, Yun YG, Jiang JH, Oh SS, Yang HD, Kim HJ, Park JY, Jeon BH, Kim SI, Park H (2005) Analysis on the antioxidant activity of catechin concentrations and green tea extract powder. J Physiol & Pathol Korean Med 19(6): 1580-1584.

- Choi SY, Kim SY, Hur JM, Shin JH, Choi HG, Sung NJ (2006) A study on the physicochemical properties of the Sargassum thunbergii. Korean J Food Nutr 19(1): 8-13.

-

Choi YM, Jeong HS, Lee JS (2007) Antioxidant activity of methanolic extracts from some grains consumed in Korea. Food Chem 103(1): 130-138.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.08.004]

- Chung EK, Seo EH, Park JH, Shim HR, Kim KH, Lee BR (2011) Anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic effect of extracts from organic soybean. Korean J Org Agric 19(2): 245-253.

-

Coward L, Barnes NC, Setchell KDR, Barness B (1993) Genistein, daidzein, and their ß-glucoside conjugates: Antitumor isoflavones in soybean foods from American and Asian diets. J Agric Food Chem 41(11): 1961-1967.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00035a027]

-

Díaz-Mula HM, Zapata PJ, Guillén F, Martínez-Romero D, Castillo S, Serrano M, Valero D (2009) Changes in hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidant activity and related bioactive compounds during post-harvest storage of yellow and purple plum cultivars. Postharvest Biol Technol 51(3): 354-363.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.09.007]

-

Giles D, Wei H (1997) Effect of structurally related flavones/isoflavones on hydrogen peroxide production and oxidative DNA damage in phorbol ester-stimulated HL-60 cells. Nutr Cancer 29(1): 77-82.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01635589709514605]

-

Halliwell B, Aeschbach R, Löliger J, Aruoma OI (1995) The characterization of antioxidants. Food Chem Toxicol 33(7): 601-617.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-6915(95)00024-V]

-

Hayes RE, Bookwalter GN, Bagley EB (1997) Antioxidnat activity of soybean flour and derivatives -A review. J Food Sci 42(6): 1527-1531.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.1977.tb08417.x]

-

Huang ZR, Hung CF, Lin YK, Fang JY (2008) In vitro and in vivo evaluation of topical delivery and potential dermal use of soy isoflavones genistein and daidzein. Int J Pharm 364(1): 36-44.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.08.002]

- Hyun MR, Lee YS, Park YH (2011) Antioxidative activity and flavonoid content of Chrysanthemum zawadskii flowers. Korean J Hortic Sci Technol 29(1): 68-73.

-

Imai J, Ide N, Nagae S, Moriguchi T, Matsuura H, Itakura Y (1994) Antioxidant and radical scavenging effects of aged garlic extract and its constituents. Planta Med 60(5): 417-420.

[https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2006-959522]

- Imm JY, Kim SJ (2010) Anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory effects of mung bean and soybean extracts. Korean J Food Sci Technol 42(6): 755-761.

-

Kanatt SR, Arjun K, Shama A (2011) Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of legume hulls. Food Res Int 44(10): 3182-3187.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2011.08.022]

- Kim SH, Ahn JH, Jeong JY, Kim SB, Jo YB, Hwang BY, Lee MK (2013) Tyrosinase inhibitory phenolic constituents of Smilax china leaves. Korea J Pharmacogn 44(3): 220-223.

- Kim SR, Hong HD, Kim SS (1999) Some properties and conetents of isoflavone in soybean and soybean foods. Korea Soybean Digest 16(2): 35-46.

- Kim SR, Kim JS, Ahn JY, Ha TY (2004) Quantitative analysis of soybean isoflavones. Korean J Crop Sci 49(1): 102-109.

-

Kurzer MS, Xu X (1997) Dietary phytoestrogen. Annu Rev Nutr 17: 353-381.

[https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nutr.17.1.353]

- Lee MH, Kan SM (2018) The antioxidation effect of Passiflora edulis f. edulis rind extract and its lnfluence on cell bioactivity. J Invest Cosmetol 14(4): 429-439.

-

Lee SC, Jeong SM, Kim SY, Park HR, Nam KC, Ahn DU (2006) Effect of far-infrared radiation and heat treatment on the antioxidant activity of water extracts from peant hulls. Food Chem 94(4): 489-493.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.12.001]

-

Leyden J, Wallo W (2011) The mechanism of action and clinical benefits of soy for the treatment of hyperpigmentation. Int J Dermatol 50(4): 470-477.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04765.x]

- Lim JM, Lee JS, Lee JH (2020) Evaluation of physiological activity of soybean extract for cosmetic material development. J Invest Cosmetol 16(1): 11-22.

- Liu K (2000) Expanding soybean food utilization. Food Technol 54(7): 46-58.

-

Marmol V, Beermann F (1966) Tyrosinase and related proteins in mammalian pigmentation. FEBS Lett 381(3): 165-168.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-5793(96)00109-3]

-

Meir S, Kanner J, Akiri B, Hadas SP (1995) Determination and involvement of aqueous reducing compounds in oxidative defense system of various senscing leaves. J Agric Food Chem 43(7): 1813-1819.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00055a012]

-

Oyaizu M (1986) Studies on products of browning reactions: Antioxidative activities of product of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn J Nutr Diet 44(6): 307-315.

[https://doi.org/10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.44.307]

-

Paine C, Sharlow E, Liebel F, Eisinger M, Shapiro S, Seiberg M (2001) An alternative approach to depigmentation by soybean extracts via inhibition of the PAR-2 pathway. J Invest Dermatol 116(4): 587-595.

[https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01291.x]

- Park JW, Lee YJ, Yoon S (2007) Total flavonoids and phenolics in fermented soy products and their effects on antioxidant activities determined by different assays. J Korean Soc Food Cult 22(3): 353-358.

-

Prakash D, Upadhyay G, Singh BN, Singh HB (2007) Antioxidant and free radical-scavenging activites of seeds and agri-wastes of some varieties of soybean (Glycine max). Food Chem 104(2): 783-790.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.12.029]

-

Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Paganga G (1997) Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds. Trends Plant Sci 2(4): 152-159.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-1385(97)01018-2]

-

Sedivy EJ, Wu F, Hanzawa Y (2017) Soybean domestication: The origin. Genetic architecture and molecular bases. New Phytol 214(2): 539-553.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14418]

-

Szymczak G, Wójciak-Kosior M, Sowa I, Zapała K, Strzemski M, Kocjan R (2017) Evaluation of isoflavone content and antioxidant activity of selected soy taxa. J Food Compos Anal 57(1): 40-48.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2016.12.015]

-

Tanaka M, Kuie CW, Nagashima Y, Taguchi T (1988) Application of antioxidative Maillard reaction products from histidine and glucose to sardine products. Nippon Suisan Gakkai Shi 54(8): 1409-1414.

[https://doi.org/10.2331/suisan.54.1409]

-

Thannickal VJ, Fanburg BL (2000) Reactive oxygen species in cell signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279(6): L1005-L1028.

[https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1005]

-

Thongchai W, Liawruangrath B, Liawruangrath S (2009) Flow injection analysis of total curcuminoids in turmeric and total anti-oxidant capacity using 2,2’-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl assay. Food Chem 112(2): 494-499.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.05.083]

-

Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MTD, Mazur M, Telser J (2007) Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 39(1): 44-84.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001]

-

Wei H, Bowen R, Cai Q, Barnes S, Wang Y (1995) Antioxidant and antipromotional effects of the soybean isoflavone genistein. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 208(1): 124-130.

[https://doi.org/10.3181/00379727-208-43844]

-

Wei H, Wei L, Frenkel K, Bowen R, Barnes S (1993) Inhibition of tumor promoter-induced hydrogen peroxide formation in vitro and in vivo by genistein. Nutr Cancer 20(1): 1-12.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01635589309514265]

-

Wei H, Zhang X, Wang Y, Lebwohl M (2002) Inhibition of ultraviolet light-induced oxidative events in the skin and internal organs of hairless mice by isoflavone genistein. Cancer Lett 185(1): 21-29.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3835(02)00240-9]

- Whang HJ, Han WS, Yoon KR (2001) Quantitative analysis of total phenolic content in apple. Anal Sci Technol 14(5): 377-383.

-

Wilson JX, Gelb AW (2002) Free radicals, antioxidants, and neurologic injury: Possible relationship to cerebral protection by anesthetics. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 14(1): 66-79.

[https://doi.org/10.1097/00008506-200201000-00014]

-

Xu B, Chang SK (2008) Characterization of phenolic substances and antioxidant properties of food soybeans grown in North Dakota-Minnesota region. J Agric Food Chem 56(19): 9102-9113.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf801451k]

- Yang ES, Hwang JS, Choi HC, Hong RH, Kang SM (2008) The effect of genistein on melanin synthesis and in vivo whitening. Microbial Biotechonl Lett 36(1): 72-81.

-

Yoo JK, Lee JH, Cho HY, Kim JG (2013) The effects of soybean protopectinase on melanin biosynthesis. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 42(3): 355-362.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2013.42.3.355]