아밀라아제 처리에 의한 메밀의 당화가 페놀화합물 함량과 항산화 활성의 증가에 미치는 영향

Abstract

This study evaluated the functional characteristics of saccharified buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) following α-amylase, β-amylase or glucoamylase treatment based on changes in soluble solid contents, rutin and quercetin contents, total polyphenols and DPPH radical scavenging activity. The results showed that the amylase treatments significantly influenced the saccharification time. Additionally, total polyphenol, rutin, and quercetin contents increased during the saccharification process; increase in phenolic compounds induced antioxidant activity. The present study demonstrated that buckwheat has a higher amount of functional compounds and higher antioxidant activity after saccharification. These results show that buckwheat saccharification can be used to increase antioxidant capacity and functional value for applications in functional food industries.

Keywords:

Fagopyrum esculentum, saccharification, amylase, rutin, quercetin, antioxidant activity서 론

메밀(Buckwheat; Fagopyrum esculentum)은 식물분류학적으로 마디풀과의 한해살이풀로, 재배 메밀과 야생 메밀은 약 20여종이 전 세계적으로 분포되어 생장하고 있다. 재배 메밀은 보통메밀과 타타리 메밀 두 종이 있으며, 우리나라를 비롯한 중국, 일본 등의 아시아지역과 유럽, 캐나다, 미국 등지에서 재배되는 메밀은 대개 보통메밀이 주를 이루고 있다(Chang KJ et al 2010). 메밀은 13%의 단백질, 2%의 지방질, 65∼70%의 탄수화물로 구성되어 있으며, 각종 수용성 단백질을 비롯하여 thiamine, lysine, glutamic acid, arginine 및 leucine과 같은 필수 아미노산 함량이 높으며, Zn, Mg, Mn, Cu, Fe 등의 무기질과 비타민 B1, B2 및 E의 함량도 높기 때문에, 영양학적으로도 유용한 식품으로 알려져 있다(Barnett S 1955; Ikeda S et al 1995; James U 1995).

현재까지 연구를 통해서 메밀은 항산화작용(Zhang M et al 2010), DNA 손상 보호 효과(Cao W et al 2008), 세포독성(Hwang EJ et al 2006), 돌연변이 억제효과(Kwak CS et al 2004), xanthine oxidase 저해 활성(Suh HJ et al 1997), 모세혈관의 투과성 향상(Havsteen B 1983), 항알러지 작용(Kim CD et al 2003), 항부종 작용(Ihme N et al 1996) 등이 있음이 확인되었다. 또한 기능성 성분으로 rutin을 비롯하여 quercetin, quercitrin, vitexin, isoquercitrin, myricetin 등의 플라보노이드 성분이 알려져 있으며, 항산화작용, 혈압저하작용, 혈관수축작용 및 항균 작용 등이 보고되어 있다(Havsteen B 1983; Lee SJ et al 2005). 그 중 rutin이 메밀에 함유된 플라보노이드들 중 함량이 가장 많은 것으로 보고되고 있으며, 이는 메밀의 다양한 기능이 rutin 함량과 밀접한 관계가 있음을 예측할 수 있게 한다(Lee MK et al 2011). 이러한 기능성 성분들의 작용은 앞서 언급한 메밀이 나타내는 다양한 기능성에 밀접한 관계가 있을 것으로 판단할 수 있다. 최근 많은 연구논문에서 폴리페놀과 플라보노이드가 가지는 항산화 작용을 증명하고 있으며(Jeong HJ et al 2010; Kim EJ et al 2012), 폴리페놀과 플라보노이드는 체내에서 생성되는 항산화 효소인 superoxide dismutase(SOD), glutathione peroxidase(GPX), ca- talase(CAT), glutathione reductase 등이 과도한 스트레스, 환경요인, 식습관, 흡연 및 생활습관 등에 의해 충분한 활성을 나타내지 못하는 것을 보완하고, 활성산소종(ROS, reactive oxygen species)에 의한 면역력 저하(Park MH et al 2000; Zhu M et al 1999), DNA 손상(Lee JM et al 2011; Park YM et al 2011), 장기 및 조직손상(Shin JG et al 1990; Graf BA et al 2005) 등을 치료 및 예방하는 효과를 나타내는 것으로 알려져 있다.

당화(saccharification)란 황산, 염산, 수산 등의 산을 이용하거나, 또는 아밀라아제 등의 효소를 사용하여 무미한 다당류를 감미가 있는 당으로 가수분해하는 것이다. 산을 이용하여 당화를 하게 되면 가수분해의 역반응으로 인해 쓴맛을 가지는 gentiobiose 등이 생성하기 때문에, 현재의 산당화는 물엿, 가루엿 제조에 일부 사용되고 있으며, 포도당, 맥아당 등의 제조에는 α-amylase와 glucoamylase를 조합하거나 branching enzyme과 β-amylase를 조합하는 등의 효소당화법이 사용되고 있다(Lee JS et al 2014). 국내에서는 쌀과 쌀코지를 사용한 항산화능을 가진 딸기죽의 개발(Kim JS et al 2012), 곡류 코지를 이용한 당화쌀죽의 개발(Hwang IG et al 2011), 혼합곡물 발효음료 개발(Lee JS et al 2014) 등으로 다양한 분야에서 당화를 응용한 연구 및 제품개발이 진행되고 있다.

본 연구에서는 메밀에 α-amylase, β-amylase 및 glucoamylase를 효소처리하여 당화시킨 뒤 시간에 따른 플라보노이드 화합물인 rutin, quercetin의 함량 변화를 확인하고, 총 폴리페놀 함량 측정 및 항산화 활성을 확인함으로써 효소처리에 따른 메밀의 생리기능 향상을 확인하고자 하였다.

재료 및 방법

1. 시료 및 효소처리

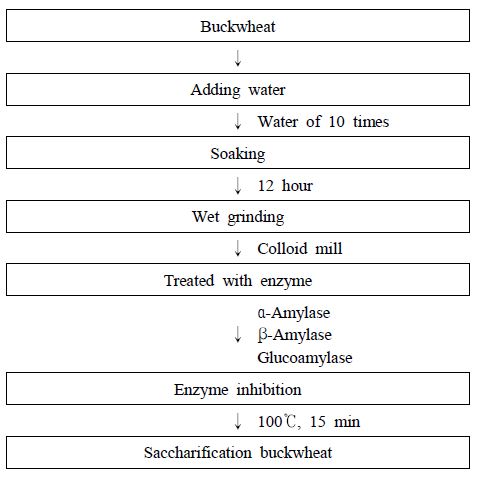

실험에 이용된 메밀은 봉평영농조합에서 판매 중인 봉평메밀을 사용하였다. 메밀을 세척한 뒤 메밀 무게의 10배의 물을 가하고 12시간동안 침지하였다. 침지 12시간 경과 후 colloid mill을 이용하여 습식분쇄하였으며, 분쇄된 메밀에 α-amylase (BAN® 480 L, Novoenzymes, Denmark), β-amylase(Betalase 1500 EL, Senson, Finland), glucoamylase(AMG 300L, Novo- enzymes, Denmark)를 중량 대비 0.2%의 농도로 처리하여 당화를 진행하였다. 24시간 후 100℃에서 15분 동안 실활하여 당화메밀을 완성하였으며, 실험에 필요한 시료는 분주하여 냉동 보관하면서 필요할 때 실험에 이용하였다(Fig. 1).

2. 당도(°Brix 측정)

당도 측정시에는 시료 5 g을 20배의 증류수에 희석하고, 균질기(wheaton, Industries, Millville, NJ)를 이용하여 균질화한 후 14,400×g에서 원심분리하여 상층액을 얻고, 이를 굴절당도계(N-50E, ATAGO, Japan)를 이용하여 측정한 뒤 °birx로 나타내었다.

3. 효소처리 시간에 따른 Rutin과 Quercetin 함량 변화량 측정

Rutin과 quercetin 함량은 Ohara T et al(1989)의 방법을 응용하여 50 mL의 volumetric flask에 당화메밀 500 mg, me- thanol 50 mL를 넣고 50℃에서 90분간 초음파 추출 후 0.45 µm membrane filter로 여과하여 HPLC로 분석하였다. 표준물질로 rutin과 quercetin (Sigma, USA)을 사용하였고, 분석조건은 Table 1과 같다.

4. 효소처리 시간에 따른 총 폴리페놀 함량 측정

총 폴리페놀 함량은 Folin-Ciocalteau’s phenol 시약을 이용하여 측정하였다(Kim JM et al 2010). 각 시료 0.2 mL와 증류수 4.8 mL, 50% Folin-Ciocalteau’s phenol(Sigma, St Louis, Missouri, USA) 0.5 mL를 잘 혼합하여 3분간 반응시킨 후 1 mL의 10% Na2CO3 용액을 첨가하여 1시간동안 반응시킨 다음, UV/VIS spectrophotometer(Optizen 2120UV, Mecasys, Korea)를 사용하여 700 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. 총 폴리페놀 화합물의 함량은 galic acid(Sigma, USA) 검량선에 의하여 산출하였다.

5. 효소처리 시간에 따른 DPPH Radical 소거능 측정

DPPH radical 소거능은 Blois MS(1958)의 방법을 변형하여 측정하였다. 증류수를 이용하여 효소처리 24시간 동안에 2시간 간격으로 채취한 시료 0.2 mL에 0.15 mM DPPH (1,1- diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) 0.6 mL를 첨가하여 암조건에서 30분간 반응시킨 후 517 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. Negative control은 증류수를 넣어 측정하고, positive control은 ascorbic acid를 사용하여 다음 계산식에 의거하여 소거활성을 측정하였다.

6. 통계분석

실험에서 얻어진 결과의 통계적 유의성은 SPSS (Statitical Package for Social Sciences) program을 이용하여 평균±표준편차로 표시하였고, one-way ANOVA test 후 Duncan’s mul- tiple range test에 의해 p<0.05 수준에서 각 실험군 간의 유의성을 검증하였다.

결과 및 고찰

1. 효소처리에 의한 당화 메밀의 당도 변화

본 실험에서는 α-amylase, β-amylase, glucoamylase로 당화한 메밀의 가용성 고형물 함량의 시간에 따른 변화가 Table 2와 같이 관찰되었다. 효소를 처리하지 않은 대조군을 기준으로 3종의 효소를 이용하여 당화시킨 메밀은 시간이 흐름에 따라 가용성 고형분 함량이 유의하게 증가하는 것으로 관찰되었다. 당화가 시작된 후 α-amylase와 glucoamylase는 16시간에 각각 10.27, 11.13 °Brix로 가장 높은 당도를 나타내었으며, β-amylase는 18시간에 5.13 °Brix를 나타내었다. Ann YG (1999)의 연구에서도 다양한 amylase의 처리가 시간 경과에 따라 당도를 향상시키는 것이 보고되어, 본 실험의 결과를 뒷받침해 주고 있다.

2. 효소처리 시간에 따른 Rutin과 Quercetin 함량 변화량 측정

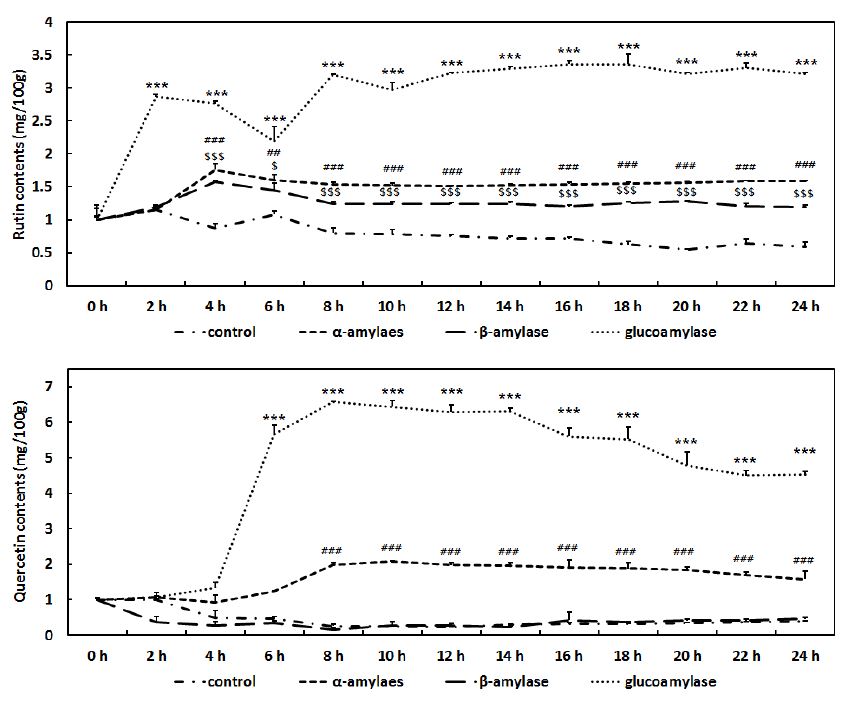

Rutin(quercetin 3-rutinoside)과 quercetin은 메밀의 주요한 기능성 성분으로 α-amylase, β-amylase, glucoamylase를 이용하여 당화를 진행한 메밀에서 시간에 따른 rutin과 quercetin 함량의 변화를 확인하였다. α-Amylase와 β-amylase를 처리한 당화메밀에서 rutin의 함량은 처리 4시간에서 약 1.76, 1.58배 각각 증가하였다가 시간경과에 따라 서서히 감소하고, quercetin은 α-amylase처리 10시간에서 약 2.09배 증가한 것이 관찰된 후 서서히 감소되는 형태가 확인되었으며, β-amylase는 quercetin 함량에 영향을 미치지 못하는 것으로 관찰되었다. Glucoamylase로 메밀을 당화를 하였을 때 rutin은 2시간 이내에 당화 전 rutin 함량의 2.87배까지 증가하다가 6시간까지 당화 전 함량의 약 2배까지 감소하다가 다시 시간이 경과함에 따라 최고 3.36배까지 증가하는 것이 확인되었으며, quer- cetin은 8시간 후 당화 전 quercetin 함량의 약 6.58배 증가하였고, 14시간 이후 서서히 감소하는 경향을 나타내었으며(Fig. 2), 이러한 감소는 glucoamyalse에 의한 당화과정에서 온도와 혼합공정의 물리적 영향과 메밀유래 미량의 분해효소에 의해 quercetin이 분해되면서 완만히 감소하는 것으로 판단된다. 이 실험을 통해 glucoamylase가 메밀의 당화과정 동안 rutin과 quercetin의 함량을 효과적으로 증가시킬 수 있음을 확인하였다. Glucoamylase의 처리에 의한 rutin 및 quercetin의 증가 이유를 설명하기 위해서는 추가적인 연구가 필요하겠지만, α-amylase와 β-amylase보다 rutin과 querectin 함량이 높이 증가한 것은 메밀을 당화하는 과정에서 α-amylase와 β-amylase보다 glucoamylase가 효과적으로 메밀의 다당류를 분해하면서 메밀에 포함되어 있는 성분이 보다 효과적으로 추출되었기 때문이라고 추측할 수 있으며, 이는 Park BJ et al (2005)의 연구에서 제시한 메밀추출물의 rutin 함량 19.8 mg/100g에서 알 수 있듯이, 메밀에는 많은 양의 rutin이 함유되어 있기 때문이다. 메밀의 당화과정은 추출과정을 거치지 않더라도 이들 기능성 화합물의 용출을 향상시킬 수 있음을 확인할 수 있었다. 또한 rutin과 quercetin이 강화된 당화메밀의 기능성에 대한 추가 연구가 필요할 것으로 판단된다.

Rutin and quercetin contents during buckwheat saccharification with respect to time.Results are presented as means±standard deviation (S.D.) of three independent experiments ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001 as compared to α amylase and the control. $p<0.05, $$$p<0.001 as compared to β-amylase and the control. ***p<0.001 as compared to glucoamylase and the control.

3. 효소처리 시간에 따른 총 폴리페놀 함량 측정

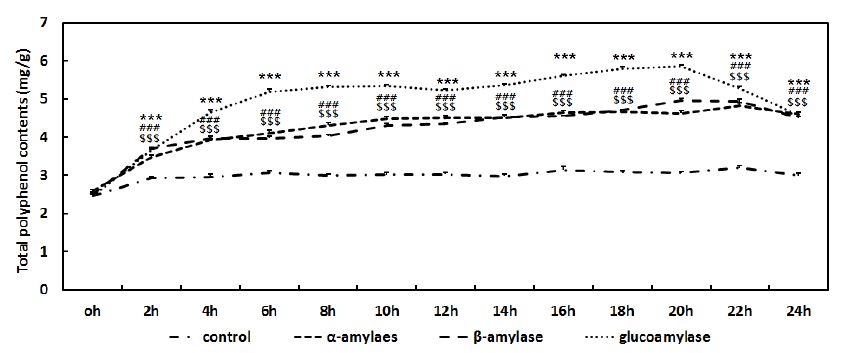

α-Amylase, β-amylase, glucoamylase로 당화한 메밀의 총 폴리페놀 함량 변화를 Fig. 3과 같이 관찰하였다. 메밀을 α-amylase, β-amylase, glucoamylase로 당화를 하게 되면 효소작용에 의해 총 폴리페놀의 함량이 증가하는 것을 확인할 수 있는데, 당화 전 2.5 mg/g의 총 폴리페놀 함량을 가지던 메밀은 α-amylase, β-amylase로 당화를 진행한 후에는 4.82 mg/g, 4.96 mg/g으로 총 폴리페놀 함량이 증가하였으며, glucoamylase로 당화한 경우 5.86 mg/g까지 총 폴리페놀 함량이 증가하다가 22시간 이후 감소하는 것이 확인되었다. Fig. 2에서 관찰한 메밀 당화에 의한 rutin과 quercetin의 함량 증가와 함께 총 폴리페놀의 함량 또한 증가하는 것이 확인되었고, 이를 통해 메밀의 당화과정이 기존 메밀의 기능을 강화시킬 수 있음을 유추할 수 있다. Seo MJ et al (2013)의 연구결과에서도 발효공정을 통해 증가된 polyphenol이 면역증강 효과를 더욱 개선한 것을 확인할 수 있었다. 그러나 polyphenol의 증가원인과 향상된 기능성에 대한 연구가 추가적으로 진행되어야 할 것으로 판단된다.

Total polyphenol contents of buckwheat during saccharification depending on the time.Results are presented as means±standard deviation (S.D.) of three independent experiments. ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001 as compared to α-amylase and the control. $p<0.05, $$$p<0.001 as compared to β-amylase and the control. ***p<0.001 as compared to glucoamylase and the control.

4. 효소처리에 따른 DPPH Radical 소거능 측정

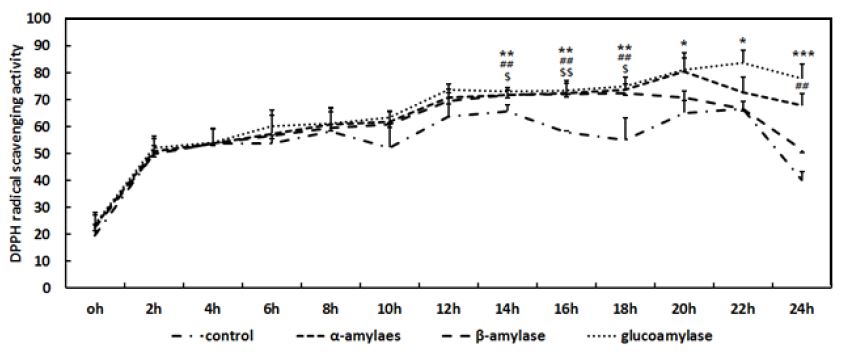

Fig. 4를 통해 α-amylase, β-amylase, glucoamylase로 당화한 메밀의 총 폴리페놀 함량이 증가한 것을 바탕으로 항산화활성이 개선될 것임을 예측할 수 있었으며, 측정결과, 당화 전 메밀의 DPPH radical 소거능은 22.18%를 나타낸 반면, α-amylase, β-amylase 및 glucoamylase로 당화를 진행한 후에는 80.36%, 72.55% 및 83.77%의 DPPH radical 소거능을 나타내었으나, 당화 시간이 22시간이 넘어가면서 DPPH radical 소거능이 감소되는 것이 확인되었다. Kim EY et al(2014)은 다양한 약용식물의 항산화 활성이 polyphenol의 함량과 관련이 있음을 보고하였고, Jeong MJ et al(2010)은 DPPH radical 소거능을 가진 유효 물질을 HPLC와 MS를 이용하여 분석한 결과, rutin과 quercetin이 주요한 물질이라고 보고하였다. 이는 본 실험에서 메밀의 당화가 rutin과 quercetin의 증가뿐만아니라, polyphenol의 증가를 유도함으로써 항산화 활성을 증가시킨다는 결과를 설명할 수 있는 기초자료가 된다.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of buckwheat during saccharification depending on the time.Results are presented as means±standard deviation (S.D.) of three independent experiments ##p<0.01 as compared to α-amylase and the control. $p<0.05, $$∖p<0.01 as compared to β-amylase and the control. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 as compared to glucoamylase and the control.

요 약

본 연구에는 메밀을 α-amylase, β-amylase, glucoamylase 세 종류의 효소로 당화한 결과, 당도와 rutin, quercetin, 총 폴리페놀 함량이 증가하였고, 항산화 활성이 개선됨을 확인하였다. 당화 전 약 1 °Brix를 나타내던 메밀은 α-amylase, β-amylase, glucoamylase로 당화하였을 때 최고 10.27 °Birx, 5.13 °Brix, 11.13 °birx를 각각 나타내었다. Rutin과 quercetin의 함량도 당화 전보다 당화를 거치면서 증가하는 경향을 나타내었으며, α-amylase로 당화하였을 때 rutin은 1.76배, quercetin은 2.09배 증가하였으며, β-amylase로 당화하였을 때 rutin은 1.58배 증가하였으며, glucoamylase로 당화하였을 때 rutin은 3.36배, quercetin은 6.58배 증가하였다. 총 폴리페놀과 DPPH radical 소거능을 측정한 결과, 당화를 하기 전과 비교하여 당화 후 총 폴리페놀 함량과 DPPH radical 소거능이 유의하게 증가하였다. 이러한 결과를 바탕으로 메밀의 당화는 메밀에 함유되어 있는 기능성 성분을 증가시켜 기능성 식품으로의 개발가능성을 높이는 것으로 판단된다.

Acknowledgments

본 결과물은 중소기업청 2014년도 산학연협력 기술개발사업(C0200466)과 강원웰빙특산물산업화지역혁신센터(B00- 09702) 및 강원대학교 생명공학연구소(320130015)의 일부 지원으로 수행한 연구 결과로 이에 감사드립니다.

REFERENCES

- Ann, YG., (1999), Preparation of traditional malt-sikhye 1. Preparation by malt and amyolytic enzymes, Korean J Food & Nutr, 12(2), p164-170.

-

Barnett, S., (1955), Nutritive value of proteins in buckwheat and their role as supplements to proteins in cereal grains, J Agric Food Chem, 3, p793-795.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf60055a010]

-

Blois, MS., (1958), Antioxidant determination by the use of a stable free radical, Nature, 181, p1199-1200.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/1811199a0]

-

Cao, W., Chen, WJ., Suo, ZR., Yao, YP., (2008), Protective effects of ethanolic extracts of buckwheat groats on DNA damage caused by hydroxyl radicals, Food Research International, 41, p924-929.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2007.10.014]

- Chang, KJ., Seo, GS., Kim, YS., Huang, SD., Park, JI., Park, JJ., Lim, YS., Park, BJ., Park, CH., Lee, MH., (2010), Components and biological effects of fermented extract from tartary buckwheat sprouts, Korean J Plant Res, 23, p131-137.

-

Graf, BA., Milbury, PE., Blumberg, JB., (2005), Flavonols, flavones, flavanones, and human health: Epidemiological evidence, J Med Food, 8, p281-290.

[https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2005.8.281]

-

Havsteen, B., (1983), Flavonoids, a class of natural products of high pharmacological potency, Biochem Pharmacol, 32, p1141-1148.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-2952(83)90262-9]

- Hwang, EJ., Lee, SY., Kwon, SJ., Park, MH., Boo, HO., (2006), Antioxidative, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of Fagopyrum esculentum Moench extract in germinated seeds, Korean J Medicinal Crop Sci, 14, p1-7.

-

Hwang, IG., Yang, JW., Kim, JY., Yoo, SM., Kim, GC., Kim, SJ., (2011), Quality characteristics of saccharified rice gruel prepared with different cereal Koji, J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr, 40, p1617-1622.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2011.40.11.1617]

-

Ihme, N., Kiesewetter, H., Jung, F., Hoffmann, KH., Birk, A., Müller, A., Grützner, KI., (1996), Leg oedema protection from a buckwheat herb tea in patients with chronic venous insufficiency: A single-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 50, p443-447.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s002280050138]

- Ikeda, S., Yamashita, Y., Murakami, T., (1995), Minerals in buckwheat, Current Advances in Buckwheat Research, p789-792.

- James, U., (1995), Buckwheat: The wonderful nutritional values of buckwheat, Pro. 6th Intl. Symp. Buckwheat at Ina, p1027-1029.

- Jeong, HJ., Lee, SG., Lee, EJ., Park, WD., Kim, JB., Kim, HJ., (2010), Antioxidant activity and anti-hyperglycemic activity of medicinal herbal extracts according to extraction methods, Korean J Food Sci Technol, 42(5), p571-577.

-

Kim, CD., Lee, WK., No, KO., Park, SK., Lee, MH., Lim, SR., Roh, SS., (2003), Anti-allergic action of buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) grain extract, Int Immunopharmacol, 3, p129-136.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S1567-5769(02)00261-8]

-

Kim, EJ., Choi, JY., Yu, M., Kim, MY., Lee, S., Lee, BH., (2012), Total polyphenols, total flavonoid contents, and antioxidant activity of Korean natural and medicinal plants, Korean L Food Sci Technol, 44(3), p337-342.

[https://doi.org/10.9721/KJFST.2012.44.3.337]

- Kim, EY., Baik, IH., Kim, JH., Kim, SR., Rhyu, MR., (2014), Screening of the antioxidant activity of some medicinal plants, Korean J Food Sci Technol, 36(2), p333-338.

-

Kim, JM., Baek, JM., Kim, HS., Choe, M., (2010), Antioxidative and anti-asthma effect of Morus bark water extracts, J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr, 39, p1263-1269.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2010.39.9.1263]

-

Kim, JS., Kim, JY., Chang, YE., (2012), The quality characteristic and antioxidant properties of saccharified strawberry gruels, J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr, 41, p752-758.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2012.41.6.752]

-

Kwak, CS., Lim, SJ., Kim, SA., Park, SC., Lee, SD., (2004), Antioxidative and antimutagenic effects of Korean buckwheat, sorghum, millet and job's tears, J Korean Soc Nutr, 33, p921-929.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2004.33.6.921]

-

Lee, JM., Park, JH., Chu, WM., Yoon, YM., Park, E., Park, HR., (2011), Antioxidant activity and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity of stings of Gleditsia sinensis extract, J Life Sci, 21(1), p62-67.

[https://doi.org/10.5352/JLS.2011.21.1.62]

-

Lee, JS., Kang, YH., Kim, KK., Lim, JG., Kim, TW., Kim, DJ., Bae, MH., Choe, M., (2014), Production of saccharogenic mixed grain beverages with various strains and comparison of common ingredients, J East Asian Soc Dietary Life, 24(1), p53-61.

[https://doi.org/10.17495/easdl.2014.02.24.1.53]

- Lee, MK., Park, SH., Kim, SJ., (2011), A time-course study of flavonoids in buckwheat (Fagopyrum species) CNU, Journal of Agricultural Science, 38(1), p78-94.

-

Lee, SJ., Kim, SJ., Han, MS., Chang, KS., (2005), Changes of rutin and quercetin in commercial gochujang prepared with buckwheat flour during fermentation, J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr, 34(4), p509-512.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2005.34.4.509]

-

Ohara, T., Ohinata, H., Muramatsu, N., Oike, T., Matsuhashi, T., (1989), Enzymatic degradation of rutin in processing of buckwheat noodle, Nippon Shokuhin Kogyo Gakkaishi, 36(2), p121-126.

[https://doi.org/10.3136/nskkk1962.36.2_121]

- Park, BJ., Kwon, SM., Park, JI., Chang, KJ., Park, CH., (2005), Phenolic compounds in common and tartary buckwheat, Korean J Crop Sci, 50(S), p175-180.

- Park, MH., Choi, C., Bae, MJ., (2000), Effect of polyphenol compounds from persimmon leaves (Diospyros kaki folium) on allergic contact dermatitis, J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr, 29(1), p111-115.

-

Park, YM., Jeong, JB., Seo, JH., Lim, JH., Jeong, HJ., Seo, EW., (2011), Inhibitory effect of red bean (Phaseolus angularis) hot water extracts on oxidative DNA and cell damage, Korean J Plant Res, 24(2), p130-138.

[https://doi.org/10.7732/kjpr.2011.24.2.130]

-

Seo, MJ., Kang, BW., Park, JU., Kim, MJ., Lee, HH., Kim, NH., Kim, KH., Rhu, EJ., Jeong, YK., (2013), Effect of fermented Cudrania tricuspidata fruit extracts on the generation of the cytokines in mouse spleen cells, Journal of Life Science, 23(5), p682-688.

[https://doi.org/10.5352/JLS.2013.23.5.682]

- Shin, JG., Park, JW., Pyo, JK., Kim, MS., Chung, MH., (1990), Protective effects of a ginseng component, maltol(2-Methyl-3-Hydroxy-4-Pyrone) against tissue damages induced by oxygen radicals, Korean J Ginseng Sci, 14(2), p187-190.

- Suh, HJ., Chung, SH., Kim, YS., Lee, SD., (1997), Free radical scavenging activities and inhibitory effects on xanthine oxidase of buckwheat (Suwon No. 5), J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr, 26, p411-416.

-

Zhang, M., Che, H., Li, J., Pei, Y., Liang, Y., (2010), Antioxidant properties of tartary buckwheat extracts as affected by different thermal processing methods, LWT-Food Science and Technology, 43, p181-185.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2009.06.020]

-

Zhu, M., Gong, Y., Yang, Z., Ge, G., Han, C., Chen, J., (1999), Green tea and its major components ameliorate immune dysfunction in mice bearing Lewis lung carcinoma and treated with the carcinogen NNK, Nutr Cancer, 35(1), p64-72.

[https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532791464-72]