Effects of Korean and US Consumers’ Environmental Concern on Green Restaurant Patronage Intention : The Mediating Role of Eco-friendly Dine-out Behavior

Abstract

This study examined the consumers' environmental concerns regarding their green restaurant patronage intention. Questionnaires were distributed in the US and South Korea. Regarding the environmental concerns, only Korean consumers' cognitive environmental concern had a direct effect on the green restaurant patronage intention. It had a mediating effect on the route from behavioral environmental concern to green restaurant patronage intention among US consumers and from cognitive environmental concern to green restaurant patronage intention among Korean consumers. These findings suggest that it is important to encourage customers to dine green by emphasizing the importance of green consumption.

Keywords:

environmental concern, eco-friendly dine-out behavior, green restaurant, patronage intentionINTRODUCTION

Consumers nowadays are shifting their purchasing values away from the self-centered perspective towards the more societal-centered perspective as concerns regarding environmental degeneration continuously increase. Consumers' awareness levels regarding the environment are rising in accordance with international circumstances and socioeconomic phenomenon. Consumer demands for businesses to align their operations with environmental needs or goals are also growing (Cone Inc. 2013). As many researches point out that management in the restaurant industry considerably involves non-sustainable aspects, consumer groups and environmental groups started movements to cut down dine-out frequencies (National Council of the Green Consumers Network in Korea [NCGCNK] 2010). Green consumers, who are defined as consumers interested in and actively make purchase decisions regarding environmental effects and can endure inconveniences caused during the process of purchase to disposal (Shrum LJ et al 1994) are rising in number.

Environmental concern regards one’s interest in environmental preservation and attitude towards environmental issues, and has mutual relationships with self-centered, altruistic and ecological factors (Minton AP & Rose RL 1997; Shultz P & Zelezny L 1999; Choi SM & Kim Y 2005). Many previous studies revealed the influence level of environmental concern has on consumers’ attitudes toward environment-friendly products and awareness levels of environmental issues (Dutcher DD et al 2007; Lee J et al 2010). Since consumers who pay much attention to the environment are expected to be supportive of pro-environmental changes, their eco-friendly dine-out behavior and green restaurant patronage intention will increase as perceived relationship between the environment and individuals, severity of environmental issues increases. Thereupon, this study expects to reveal the relationships among environmental concern, eco-friendly dine-out behavior and green restaurant patronage intention.

Eco-friendly behavior is a state of emotional engagement with environmental values, knowledge and attitude combined altogether (Kollmuss A & Agyeman J 2002), and in which an individual constantly cares about and behaves within concern of social and environmental benefits (Peattie K 2001). In addition, environmentally friendly consumption activities are related to green consumption and sustainable consumption. Eco-friendly consumption behavior is about making decisions while thinking about the environmental consequences that would follow one's actions, and thus acting responsible. This definition was adopted and further developed to establish the meaning of environmentally friendly food consumption activities: trying to minimize food waste during the entire process of food preparation from planning a meal to storing leftover food. This study combines the given definitions to form a comprehensive survey to measure eco-friendly dine-out behavior. Eco-friendly dine-out behavior was defined as the effort of trying to minimize food waste and energy consumption during the entire process of dining out.

Many restaurants are recently making efforts to preserve the environment, save energy, and minimize pollution as part of a social responsible action (Jang YJ et al 2010; Liou YW & Namkung Y 2012). Among these efforts is the rise of green restaurants. Green restaurants are defined as restaurants that balance with the environment by saving resources and minimizing environmental pollution (Jang YJ et al 2010; Kim YJ & Kim DJ 2012). Saving energy, recycling, using recycled goods, utilizing environment-friendly ingredients (e.g. organic or local foods), and environmental training are all actions taken by green restaurants (Nielsen B 2004; Hu H et al 2010). Lorenzini B (1994) defined green restaurants as “new or renovated structures designed, constructed, operated, and demolished in an environmentally friendly and energy efficient manner. The National Restaurant Association (NRA) of the US established the Green Restaurant Association (GRA), an organization that certifies eco-friendly restaurants of the nation, to restrain the problem. GRA proposed a comprehensive environmental standard for restaurants willing to put into place green practices, Green Restaurant 4.0 Standard (Green Restaurant 4.0 Standards, 2012). Simply adopting the GR 4.0 Standard in its present form to Korea may be difficult due to major differences in governmental policies and other environmental certifications. Nonetheless, no environmental indicators or criteria exist for restaurants industry, and being green is somewhat unfriendly to many restaurants in Korea. High initial investment and maintenance costs are main barrier, in addition, practicing green can be a burden to many foodservice managers in reality. Sometimes, the perception and the practical actions of owners and managers did not match their ethics (Han & Yoon, 2013).

Patronage intention is the effect of one’s attitude and norms on behavior, and can be defined as the subjective probability that this would shift to his faith, attitude and behavior (Ajzen I & Fishbein M 1977; Engel JF et al 2007). It can also be defined as the intention to decide on the favorite alternative among several of them when regarding a service product (Zeithaml VA et al 1996). Based on such definitions, this study defines green restaurant patronage intention as the intention to visit green restaurants. However, an insufficient amount of research has been conducted on consumers’ pro-environmental actions within the restaurant industry, and even less research has been done on comprehensive acknowledgement and importance of dine-out consumers’ awareness levels regarding green restaurant patronage intention. This study focused on understanding consumer awareness levels regarding green restaurants, and discovering the effect consumers’ environmental concern has on green restaurant patronage intention.

Korean consumers value time and efficiency more than consuming green (Won JH & Chung JE 2015), while US consumers tend to purchase eco-friendly and sustainable products despite some inconveniences caused (Environmental Leader 2008; National Restaurant Association [NRA] 2011). By comparing levels of environmental concern and the effects they have on consumers' green restaurant patronage intention in both countries, this study will provide up-to-date information on dine-out consumer behavior for marketing operators in the hospitality industry. Furthermore, results are expected to contribute to the market for establishing precise societal marketing strategies by examining how each attribute influences consumers’ green restaurant patronage intention.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A survey was developed to discover and measure respondents’ psychological awareness of factors and to determine the casual relationships among them. The survey composed of four main sections: environmental concern, eco-friendly dine-out behavior, green restaurant patronage intention, and demographics. Questionnaires and results of previous studies were looked into as reference for developing a suitable measurement tool for this survey (Ajzen I & Fishbein M 1977; Cherry J 2006; Kim YJ & Kim DJ 2012; Han JY & Yoon JY 2014; Oh JC & Yoon SJ 2014; Hassan LM et al 2016).

410 online self-administered questionnaires each were distributed to consumers of the US and South Korea who dine out on a regular basis of at least once a month. Sample size was determined according to calculations based on the formula widely used among social science studies (Salant P & Dillman DA 1994). Professional survey agencies were used (Qualtrics in the US, Embrain in South Korea) as platforms to collect survey responses online. The survey was undertaken from January to February 2016. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB#: SMWU-1504-HR-004).

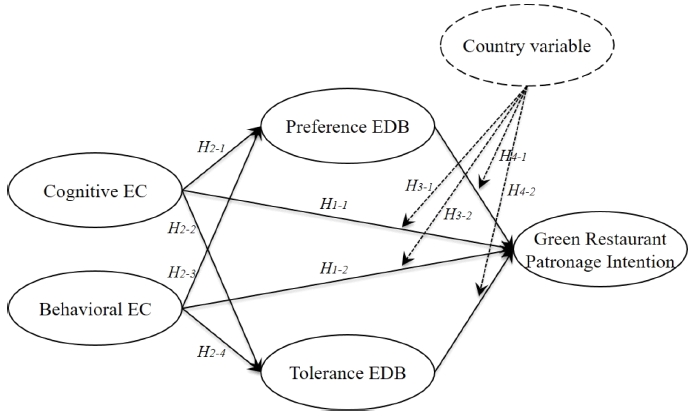

Collected data were analyzed via SPSS (v22.0) and AMOS (v22.0). An exploratory factor analysis was conducted on each construct as a preliminary analysis, and two factors each were extracted for environmental concern and eco-friendly dine-out behavior. Environmental concern was divided into cognitive and behavioral factors, while eco-friendly dine-out behavior was divided into preference and tolerance factors. Results of EFA are shown in Table 1. A path analysis model was then proposed to identify the influence each environmental concern factor has on green restaurant patronage intention, and to confirm the mediating effect of eco-friendly dine-out behavior. Lastly, country variable was used as a moderating factor to see if there were any differences between US consumers and Korean consumers. The research model is shown in Fig. 1.

Hypotheses tested in this study are as below.

H1-1: Cognitive environmental concern will affect green restaurant patronage intention.

H1-2: Behavioral environmental concern will affect green restaurant patronage intention.

H2-1: Preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior will have a mediating effect on cognitive environmental concern’s effect on green restaurant patronage intention.

H2-2: Tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior will have a mediating effect on cognitive environmental concern’s effect on green restaurant patronage intention.

H2-3: Preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior will have a mediating effect on behavioral environmental concern’s effect on green restaurant patronage intention.

H2-4: Tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior will have a mediating effect on behavioral environmental concern’s effect on green restaurant patronage intention.

H3-1: The effect cognitive environmental concern has on green restaurant patronage intention will differ according to country.

H3-2: The effect behavioral environmental concern has on green restaurant patronage intention will differ according to country.

H4-1: The mediating effect of preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior will differ according to country.

H4-2: The mediating effect of tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior will differ according to country.

Exploratory factor analysis results of environmental concern (EC) and eco-friendly dine-out behavior (EDB)

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

1. General Characteristics of Respondents

A total of 755 surveys were collected, and 751 usable responses were used for analysis. The number of surveys used from respondents of the US and Korea were 409 and 342 responsively. Of these 751 participants, 441 were women (58.7%) and 310 were men (41.3%). A majority of the respondents were in their 20s (31.7%), were students (29.2%), had a college/university degree (36.4%), and had a weekly dine-out frequency of 2∼4 times (52.2%). Table 2 shows the overall demographics of respondents.

2. Reliability and Validity of Measurement Models

Prior to verifying research hypotheses, reliability test and validity test were conducted on variables to be used in the analysis. Anderson and Gerbing's two-step approach (Anderson JC & Gerbing DW 1988) of examining individual constructs and a structural model consequently was adopted. A reliability test is used to check the internal consistency of measurement items per variable under different conditions and settings (Vitolins MA et al 2000). Environmental concern, eco-friendly dine-out behavior and green restaurant patronage intention were constructs used in this study. Environmental concern composed of cognitive (6 items) and behavioral (4 items) subordinate concepts, and eco-friendly dine-out behavior composed of preference (4 items) and tolerance (4 items) subordinate concepts. Green restaurant patronage intention (5 items) composed as a single dimension. Cronbach's α was used to measure reliability of constructs, and Table 3 shows that all reliability estimates of all factors were between .731 and .922, indicating fair reliability (Bagozzi RP & Yi Y 1988).

Construct validity is checked to examine whether a scale accurately measures the desired concept or attribute (Peter JP 1981). Convergent validity indicates the degree of correlation between items and their measured corresponding constructs (Anderson JC & Gerbing DW 1988). In order to test convergent validity, this study conducted a confirmatory factor analysis, and AMOS 22.0 was used for the testing. Validity is considered to be satisfactory if factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) are above .5 in general (Urbach N & Ahlemann F 2010). All constructs passed the convergent validity test on an acceptable level as factor loadings ranged from .466 to .873 and their AVE values were close to and above .5. Table 4 shows the convergent validity results of variables. AVE values for behavioral environmental concern, preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior, and tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior were under .5 with values of .488, .483 and .366 respectively, but were used for analysis since their indicator loadings, Cronbach's α and construct reliability were at acceptable levels.

3. Hypotheses Testing Results

This study was structured to test the effects environmental concern has on green restaurant patronage intention, with eco-friendly dine-out behavior as a mediating factor. The modified path analysis model is shown in Fig. 1. The model fit indices were χ2=784.295 (df=217, p=0.000), p=0.000, GFI=0.913, AGFI=0.889, RMR=0.045, NFI=0.929, CFI=0.947, RMSEA=0.059 each. Although AGFI was slightly under .9, the model was used for analysis without modification since GFI, NFI, CFI, RMR and RMSEA were all at acceptable levels. Table 5 shows results of hypothesis verification for H1-1 and H1-2.

Hypothesis 1-1 'Cognitive environmental concern will affect green restaurant patronage intention' was dismissed with a .019 path coefficient (CR=0.341, p>0.05). Hypothesis 1-2 'Behavioral environmental concern will affect green restaurant patronage intention' was also dismissed with a .080 path coefficient (CR=1.123, p>0.05).

Hypotheses 2-1 to 2-4 were tested by checking each direct, indirect and total effect cognitive and behavioral environmental concern has on green restaurant patronage intention with preference and tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behaviors as mediating variables. Bootstrapping method was used to check significance of each indirect effect. As shown in Table 6, cognitive environmental concern and behavioral environmental concern both had indirect effects on green restaurant patronage intention with preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior and tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior as parameters (p<0.05). Both eco-friendly dine-out behavior factors are noticeable in that they create significant indirect effects, while no direct effects exist between each environmental concern factor and green restaurant patronage intention.

A multi-group analysis between US consumers and Korean consumers was conducted to test hypotheses 3-1 to 4-2. US respondents and Korean respondents were divided into separate groups, and χ2 difference between factor loadings of the constrained model and the unconstrained model were tested by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis. χ2 was 1,087.933 for the unconstrained model (df=434) and 1,111.903 for the constrained model (df=452). Measurement invariance was confirmed (△χ2=23.97, df=18), as △χ2 was below 28.87 and CFI, TLI and RMSEA did not show much difference between the two models. Table 7 shows results of the measurement invariance test.

The difference in path coefficients between groups was then verified. Path coefficients for both groups are shown in Table 8. Cognitive environmental concern had a significant effect on tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior, behavioral environmental concern on both preference and tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior, and preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior on green restaurant patronage intention among US consumers. Cognitive environmental concern had significant effects on preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior, tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior and green restaurant patronage intention, behavioral environmental concern on preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior, and preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior on green restaurant patronage intention among Korean consumers. Neither behavioral environmental concern nor tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior had a significant effect on green restaurant patronage intention in both countries.

An additional χ2 comparison was conducted between the unconstrained model and the constrained model in order to verify for any significances of path coefficients between the two groups within the structural model. Path coefficient comparison between US consumers and Korean consumers are shown in Table 9. Significances were identified in paths of cognitive environmental concern to tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior (△χ2/df=10.006) and behavioral environmental concern to tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior (△χ2/df=4.239). This indicates that the effect cognitive environmental concern has on tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior is statistically significant and strong among Korean consumers than among US consumers.

4. Discussion

According to the results of this study, environmental concern positively affected green restaurant patronage intention among both Korean and US consumers. As green restaurant patronage intention is a desire to perform an eco- friendly act, this study's findings coincide with previous studies indicating that in general, there is a positive relationship between environmental concern and eco-friendly behavior. Minton AP & Rose RL (1997) stated that consumers with higher environmental concern reduce environment polluting consumption and are more active in making eco-friendly behavioral decisions, and Takaacs-Saanta A (2007) considered high levels of environmental concern to be important precedence factors for long-term and continuous eco-friendly behavior. In this study, between the two eco-friendly dine-out behaviors, only preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior had a mediating effect on the relationship between environmental concern and green restaurant patronage intention. Such results are speculated to appear, due to Korean consumers' low trust levels in green restaurants and US consumers' range of choice to practice eco-friendly consumption. With no official green restaurant certifying system in place, Korean consumers with high tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior doubt that restaurants claiming to be 'green' effectively carry out proenvironmental management policies. In addition, US consumers have many other ways to practice their environmental support while dining, such as visiting local restaurants or eating in instead.

As for the difference between Korean and US consumers discovered in this study, Korean consumers with higher cognitive environmental concern levels intended to visit green restaurants, while US consumers with higher behavioral environmental concern levels intended to do so. Such results could be related to the consumer decision journey. According to Court D et al (2009), consumers make their decisions regarding consumption in the order of awareness, familiarity, consideration, purchase, and loyalty. This sequence of decision making shows how consumers first perceive a problem and consider their possible options before moving on to acting out their desires through behavior. In other words, the phase of cognition comes before the phase of behavior. As shown in previous studies, it can be presumed that US consumers are in the phase of behavior. Schubert F et al (2010) showed many positive results in their study on consumer awareness of green restaurants among US consumers; a majority of respondents showed intentions to dine at green restaurants in attempts to help preserve the environment, and supported restaurants participating in pro-environmental acts. Reducing usage of energy, reducing waste, using re-usable products were strongest among US consumers, regarding willingness to act in order to preserve the environment. Other results showed that consumers also believed that green restaurants would have a competitive advantage in the future (Choi SM & Kim Y 2005; Hu H et al 2010; Schubert F et al 2010). The Green Restaurant Association (GRA 2010) discovered that 79% of consumers were willing to choose certified green restaurants over those without authentication. Korean consumers' perception of eating green, on the other hand, started later than that of US consumers did. Korean consumers are moving towards the behavioral phase, but are yet in the phase of having high cognition levels. This may have resulted in cognitive environmental concern influencing green restaurant patronage intention in this study.

Despite such differences, it is clear that consumers' environmental concern positively affects their green restaurant patronage intention. This illustrates the importance of increasing consumer environmental concern in order to expand the green restaurant industry. Various business groups have pointed out environmentalism as the next most important issue in management, and such importance has created a new domain chasing both environmental protection and business profit such as ecological marketing. According to research results of previous studies, the restaurant industry especially influences environmental and individual health aspects, and is thus especially obligated to join the movement by developing efficient ecological marketing strategies (Lee SH et al 2007). Restaurant marketing operators should especially target customers with higher levels of preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior. This study’s findings indicate that effective marketing strategies for green restaurants should be focusing on sending out messages of the importance of dining green, and advertising about what pro-environmental efforts the restaurants are already making. However, as results show behavioral eco-friendly dine-out behavior to not influence consumers' willingness to visit green restaurants, it is less recommended to practice green by sacrificing customer convenience. Since customers willing to visit green restaurants are those who believe acting green is important despite their unwillingness to endure inconveniences, green restaurants should focus more on what the restaurant can do instead of asking customers to participate in dining green by action.

CONCLUSION

This study focused on understanding consumer awareness levels regarding green restaurants, and discovering consumers’ environmental concern’s effects on green restaurant patronage intention. Questionnaires were distributed in the US and South Korea. Preliminary analysis divided environmental concern into cognitive and behavioral factors and eco-friendly dine-out behavior into preference and tolerance factors. A path analysis model was used to identify casual relationships among factors. Regarding environmental concern, only Korean consumers’ cognitive environmental concern had a direct effect on green restaurant patronage intention. As for eco-friendly dine-out behavior as a mediating factor, only preference eco-friendly dine-out behavior was significantly meaningful. It had a mediating effect on the route from behavioral environmental concern to green restaurant patronage intention among US consumers and from cognitive environmental concern to green restaurant patronage intention among Korean consumers. Tolerance eco-friendly dine-out behavior had no mediating effect on any path.

In conclusion, it is important to encourage dine-out customers to dine green by emphasizing the importance of green consumption. Restaurant managers should be careful not to put green practices before customer convenience, for this study’s findings indicate that customers are not willing to sacrifice their convenience to dine green, despite their cognition of the importance of preserving the environment by dining green. In addition, in regard of scholar practices, future research may address the difference between US consumers and Korean consumers as a difference in consumption phase and expand this into a new model to unveil casual relationships of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Sookmyung Women’s University under Grant number 1-1503-0144.

References

-

Ajzen, I, Fishbein, M, (1977), Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research, Psychol Bull, 84(5), p888-918.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.84.5.888]

-

Anderson, JC, Gerbing, DW, (1988), Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach, Psychol Bull, 103(3), p411-423.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.103.3.411]

- Bagozzi, RP, Yi, Y, (1988), On the evaluation of structural equation model, J Acad Mark Sci, 16(1), p74-94.

-

Cherry, J, (2006), The impact of normative influence and locus of control on ethical judgments and intentions: A cross-cultural comparison, J Bus Ethics, 68(2), p113-132.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9043-3]

- Choi, SM, Kim, Y, (2005), Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE, Adv Consum Res, 32, p592-599.

- Cone Inc., (2013), Global CSR report, http://www.conecomm.com/2013-global-csr-study-release Accessed March 2, 2018.

- Court, D, Dave, E, Mulder, S, Vetvik, OJ, (2009), The consumer decision journey, McKinsey Quarterly, June, 2009, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-insights/the-consumer-decision-journey Accessed February 21, 2018.

-

Dutcher, DD, Finley, JC, Luloff, AE, Johnson, JB, (2007), Connectivity with nature as a measure of environmental values, Environ Behav, 39(4), p474-493.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506298794]

- Engel, JF, Blackwell, RE, Miniard, PW, (1990), Consumer Behavior, 6th ed., Dryden Press, Chicago, USA, p4.

- Environmental Leader, (2008), Dunkin' donuts opens its first LEED restaurant, Energy & Environmental News for Business, https://www.environmentalleader.com/2008/10/dunkin-donuts-opens-its-first-leed-restaurant/ Accessed January 2, 2018.

- Green Restaurant Association, (2010), Consumer’s green dining habits. Green Restaurant Association May 2010 Project, 3258, https://www.slideshare.net/2010GRA/consumers-green-dining-habits Accessed February 21, 2018.

- Green Restaurant Association, (2012), Green restaurant 4.0 standards, http://www.dinegreen.com Accessed December 15, 2017.

- Han, JY, Yoon, JY, (2013), A study on consumers’ green practices and exploration of significant factors in green restaurants, J Tour Leus Res, 25(2), p323-342.

- Han, JY, Yoon, JY, (2014), Developing management criteria for Korean green restaurants: A modified Delphi method, J Foodservice Manage Soc Korea, 17(3), p237-260.

-

Hassan, LM, Shiu, E, Shaw, D, (2016), Who says there is an intention-behavior gap? Assessing the empirical evidence of an intention-behavior gap in ethical consumption, J Bus Ethics, 136(2), p219-236.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2440-0]

-

Hu, H, Parsa, HG, Self, J, (2010), The dynamics of green restaurant patronage, Cornell Hosp Q, 51(3), p344-362.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965510370564]

-

Jang, YJ, Kim, WG, Bonn, MA, (2010), Generation Y consumers’ selection attributes and behavioural intentions concerning green restaurant, Int J Hosp Manag, 30(4), p803-811.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.12.012]

- Kim, YJ, Kim, DJ, (2012), Consumers’ intention to select eco-friendly restaurants by adopting extended theory of reasoned action, Foodservice Ind J, 8(2), p45-62.

-

Kollmuss, A, Agyeman, J, (2002), Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior?, Environ Educ Res, 8(3), p239-260.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620220145401]

-

Lee, J, Hsu, L, Han, H, Kim, Y, (2010), Understanding how consumers view green hotels: How a hotel’s green image can influence behavioral intentions, J Sustain Tour, 18(7), p901-914.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003777747]

- Lee, SH, Kim, MY, Park, SK, (2007), The study of the consumers’ attitudes toward fashion counterfeit and brand equity - Focusing on mediate role of brand attachment, J Consum Cult, 10(3), p87-104.

- Liou, YW, Namkung, Y, (2012), The effects of restaurant green practices on perceived quality, image and behavioral intention, Korean J Hosp Admin, 21(2), p113-130.

- Lorenzini, B, (1994), The green restaurant, part II: Systems and service, Restaurant & Institutions, 104(11), p119-136.

-

Minton, AP, Rose, RL, (1997), The effects of environmental concern on environmentally friendly consumer behavior: An exploratory study, J Bus Res, 40(1), p37-48.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0148-2963(96)00209-3]

- National Council of the Green Consumers Network in Korea, (2010), 10 green ways to reduce CO2, http://www.gcn.or.kr/gcnbbs/goodguide.html Accessed March 1, 2018.

- National Restaurant Association, (2011), 2011 Restaurant Industry Fact Sheet, Washington DC, http://www.restaurant.org Accessed March 1, 2018.

- Nielsen, B, (2004), Dining green: A Guide to Creating Environmentally Sustainable Restaurants and Kitchens, Green Restaurant Association, Sharon, Mass, p1-28.

-

Oh, JC, Yoon, SJ, (2014), Theory-based approach to factors affecting ethical consumption, Int J Consum Stud, 38(3), p278-288.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12092]

-

Peattie, K, (2001), Golden goose or wild goose? The hunt for the green consumer, Bus Strategy Environ, 19(4), p187-199.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.292]

-

Peter, JP, (1981), Construct validity: A review of basic issues and marketing practices, J Mark Res, 18(2), p133-145.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/3150948]

- Salant, P, Dillman, DA, (1994), How to Conduct Your Own Survey, John Wiley & Sons Inc, New York, NY, p53-72.

-

Schubert, F, Kandampully, J, Solnet, D, Kralj, A, (2010), Exploring consumer perceptions of green restaurants in the US, Tour Hosp Res, 19(4), p286-300.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/thr.2010.17]

- Schultz, P, Zelezny, L, (1999), Values as predictors of environmental attitudes: Evidence for consistency across 14 countries, J Enviro Psychol, 19(3), p255-265.

-

Shrum, LJ, Lowrey, TM, McCarty, JA, (1994), Recycling as a marketing problem: A framework for strategy development, Psychol Mark, 11(4), p393-416.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220110407]

- Takacs-Santa, A, (2007), Barriers to environmental concern, Human Ecol Rev, 14(1), p26-38.

- Urbach, N, Ahlemann, F, (2010), Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares, J Inf Technol Theory Appl, 11(2), p5-40.

-

Vitolins, MZ, Rand, CS, Rapp, SR, Ribisl, PM, Sevick, MA, (2000), Measuring adherence to behavioral and medical interventions, Contemp Clin Trials, 21(5), p88-194.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00077-5]

- Won, JH, Chung, JE, (2015), The segmentation of single-person households based on Sheth’s theory of consumption value, J Consum Stud, 26(1), p73-99.

-

Zeithaml, VA, Berry, LL, Parasuraman, A, (1996), The behavioral consequences of service quality, J Mark, 60(2), p31-46.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1251929]