한국인의 안토시아닌 섭취량과 주요 급원식품

Abstract

This study aimed to estimate daily intake of anthocyanins and to identify major sources of anthocyanins in current Korean dietary patterns in order to implement dietary recommendations for the improvement of Korean health. Sixteen foods were selected based on the availability of food intake and reliable anthocyanin content. Food intake data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2014 and anthocyanin content data from earlier investigations were used to calculate the consumption of anthocyanins. Anthocyanin contents of 16 foods varied significantly and exhibited a range of 0∼4,009 mg/100 g of fresh weight. Daily intake of anthocyanins was estimated to be 3.3 mg to 95.5 mg in Koreans. Of the 16 foods studied, the source contributing most to anthocyanin intake in the Korean population was plums (35.1%), followed by black beans (17.1%) and grapes (15.2%). These results indicate that major foods contributing to anthocyanin consumption in the Korean dietary pattern are fruits and grains.

Keywords:

Anthocyanin, daily intake, contributing food, plum, black bean서 론

안토시아닌은 적색, 자색, 청색을 나타내는 수용성 색소로서 식물의 열매, 꽃, 잎, 뿌리 등에 널리 분포되어 있다(Kong JM 등 2003; Winkel-Shirley B 2001). 안토시아닌의 항암, 항알러지, 항바이러스, 항산화, 항염증 활성이 알려지면서(Nabavi SF 등 2015; Hribar U & Ulrih NP 2014; Yoshimoto 등 2001; He J & Giusti MM 2010), 식품산업에서 안토시아닌 함유 식품이 건강보조식품, 착색제 등으로 이용되고 있다. 최근 컬러푸드에 대한 관심이 높아지면서 안토시아닌 색소에 의한 보라색 식품의 섭취량이 높아지고 있다. 보라색 식품은 블루베리, 포도, 흑미, 오디, 복분자, 자두, 자색고구마, 자색양파, 가지 등을 포함한다. 최근에는 자색고구마와 흑미의 다양한 품종이 개발되었으며, 음료, 과자, 떡의 원료로 사용되고 있다(Liu YN 등 2013; Joo SY & Choi HY 2012). 지금까지 안토시아닌을 함유한 보라색 식품에 대한 국내 연구는 검정콩, 블루베리, 포도 등에 집중되어 있다(Chung KW 등 2004; Kim HB 2003; Lee MK 등 2016).

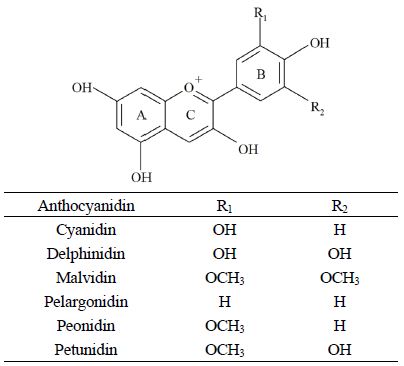

안토시아닌은 비당체인 안토시아니딘의 수산기(-OH)에 당이 결합된 배당체이다. 자연계에서 30여 개의 안토시아니딘이 발견되었지만, 식품에서는 6종의 안토시아니딘(시아니딘, 델피니딘, 말비딘, 펠라고니딘, 페오니딘, 페투니딘) (Fig. 1)이 주로 보고되었다. 일부 안토시아닌은 배당체의 당부분이 방향족산(aromatic acid) 또는 지방족산(aliphatic acid)과 에스테르 결합된 아실화(acylated) 화합물로 존재하기도 한다(Anaga A 등 2013; Francis FJ & Markakis PC 1989). 안토시아닌의 화학구조에 따라 극성(polarity), 공간적 배열(spatial structure), 체내 세포막 투과성 등이 달라지게 되어 식품의 가공 및 저장과정뿐만 아니라, 체내 흡수에서 안토시아닌의 안정성과 생리활성에 차이가 난다고 보고되었다(Zhao CL 등 2017). 이는 안토시아닌 섭취가 한국인의 건강에 미치는 영향을 밝히기 위해서는 안토시아닌의 섭취량을 보다 정확하게 추정하고, 안토시아닌의 주요 급원식품과 각 식품에 존재하는 화학적 구조에 따른 생리활성에 대한 연구가 선행되어야 함을 의미한다.

지금까지 식품 섭취를 통한 한국인의 안토시아닌 총 섭취량을 추정한 연구는 전무하다. 한국인의 총 안토시아닌 섭취량을 추정하기 위해서는 각 식품의 안토시아닌 함량과 섭취량 자료가 확보되어야 한다. 식품섭취량 자료는 매년 실시되고 있는 국민건강영양조사 자료를 이용하여 산출이 가능하다. 하지만, 식품의 안토시아닌 함량은 품종, 재배조건, 수확시기, 기후, 토양 등에 따라 달라질 수 있으므로(Connor AM 등 2002; Piccaglia R 등 2002; Lachman J 등 2012), 기존 연구결과를 검토하여 신뢰성 있는 자료를 선별하는 과정이 선행되어야 한다.

따라서, 본 연구에서는 첫 단계로 지금까지 보고된 안토시아닌 분석결과를 이용하여 한국인의 안토시아닌 섭취량을 추정하고자 하였다. 대표식품의 안토시아닌 함량 자료를 검색하여 선별하고, 2014년 국민건강영양조사 원시자료를 이용하여 한국인의 식품별 1일 섭취량을 산출하고, 복합표본설계 데이터 분석을 통한 한국인의 안토시아닌 총 섭취량을 도출하였다. 두 번째 단계로 한국인의 식생활에서 안토시아닌의 주요 급원식품을 알아보고자 하였다.

재료 및 방법

1. 대상 식품 선정 및 섭취량 자료

문헌조사를 통해 안토시아닌이 존재한다고 보고된 식품 목록을 작성하고, 2014년 국민영양통계에서 식품의 1인 1일 평균 섭취량을 인용하거나, 2014년 국민영양통계(Korea Health Industry Development Institute 2016)에 섭취량 자료가 제시되지 않은 식품은 2014년 국민건강영양조사 원시자료를 통계처리하여 1일 섭취량을 산출하였다. 자색을 띠는 일부 식품(자색양파, 자색옥수수, 아로니아, 아사이베리 등)은 2014년 국민건강영양조사 원시자료에 식품코드가 존재하지 않아서 본 연구에서 제외되었다.

2. 안토시아닌 자료 수집

관련 논문을 조사하기 위해 첫 단계로 Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Medline, Web of Science 사이트를 통해 안토시아닌(anthocyanin), 정성(identification, profile, qualification, individual), 정량(quantification), 함량(concentration, content), 식품명, 학명으로 검색하였다. 검색어로 사용된 식품명 또는 학명은 가지(eggplant), 검정콩(black bean), 딸기(strawberry), 머루(moeru, Vitis coignetiae), 버찌(sweet cherry, sour cherry, tart cherry, Prunus avium L., Prunus cerasus L.), 복분자(bokbunja, Rubus coreanus), 블루베리(blueberry), 산딸기(Rubus crataegifolius), 석류(pomegranate), 앵두(Prunus tomentosa), 오디(mulberry), 오미자(omija, Schisandra chinensis), 자두(plum, Prunus salicina), 자색감자(red or purple potato), 자색고구마(sweet potato, purple sweet potato), 자색양배추(red cabbage), 적겨자(red mustard), 콜라비(kohlrabi), 크랜베리(cranberry), 포도(grape), 흑미(black rice)였다. 두 번째 단계는 검색된 논문에 인용된 참고문헌을 개별적으로 확인하여 관련 논문을 추가 검색하였다. 세 번째 단계는 검색된 논문 중에서 액체크로마토그래피(HPLC)를 이용하여 안토시아닌을 분리하고, 정량한 연구결과를 선별하여 안토시아닌 함량을 정리하였다. 네 번째 단계는 안토시아닌 함량을 통합하기 위해 건조 중량 기준으로 보고된 논문의 자료는 제8개정판 식품성분표(Rural Development Administration 2011)의 수분함량을 참고하여 생중량으로 환산하여 통합되었다. 다섯 번째 단계는 한국농촌경제연구원의 ‘중장기양곡정책 방향’ 연구보고(Kim T 등 2015)와 ‘식품별 수입산 이용 비율’(Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs 2015)을 참고하여 식품별 국내 논문과 국외 논문의 비율이 조정되었다.

3. 안토시아닌 섭취량 산출

2014년 국민영양통계(Korea Health Industry Development Institute 2016)의 식품별 1인 1일 섭취량과 2014년도 국민건강영양조사 제6기 2차년도 원시자료를 통계처리하여 산출된 1인 1일 섭취량에 식품별 안토시아닌 함량을 곱하여 한국인의 1인 1일 안토시아닌 총 섭취량을 산출하였다.

각 식품의 안토시아닌 1인 1일 섭취량을 합하여 한국인의 1인 1일 안토시아닌 총 섭취량을 도출하였다.

식품별 안토시아닌 1인 1일 섭취량(mg/day) = 식품 섭취량(g/day) × 안토시아닌 함량(mg/g)

4. 통계처리

통계 분석은 SPSS 21.0 program(SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)를 이용하여 복합표본설계 데이터 분석을 통한 한국인의 안토시아닌 섭취량을 산출하였다.

결과 및 고찰

1. 대상 식품 선별

식품섭취량 자료가 존재하는 식품 21종(가지, 검정콩, 딸기, 머루, 버찌, 복분자, 블루베리, 산딸기, 석류, 앵두, 오디, 오미자, 자두, 자색감자, 자색고구마, 자색양배추, 적겨자, 콜라비, 크랜베리, 포도, 흑미)을 연구대상으로 선정하였다. 포도는 과일뿐만 아니라, 주스, 포도주로 가공되어 섭취되는 비율이 높기 때문에 포도주스와 포도주가 포함되었으며, 딸기의 경우에는 주요 가공품인 딸기잼이 추가되었다.

가지, 딸기, 머루, 버찌, 복분자, 블루베리, 산딸기, 석류, 앵두, 오디, 오미자, 자두, 적겨자, 콜라비, 크랜베리, 포도, 포도주는 2014년 국민영양통계 자료집의 섭취량을 이용하였다. 2014년 국민영양통계(Korea Health Industry Development Institute 2016)에 섭취량이 제시되지 않은 검정콩, 딸기잼, 자색감자, 자색고구마, 자색양배추, 포도주스, 흑미는 2014년 국민건강영양조사 원시자료를 이용하여 식품별 1일 섭취량을 산출하였다. 최근에 섭취량이 증가되고 있는 자색고구마와 자색감자의 경우에는 가장 최근 발표된 국민건강영양조사 원시자료에 식품코드는 설정되어 있지만, 섭취량 자료는 ‘0’이었다.

2. 안토시아닌 자료 수집

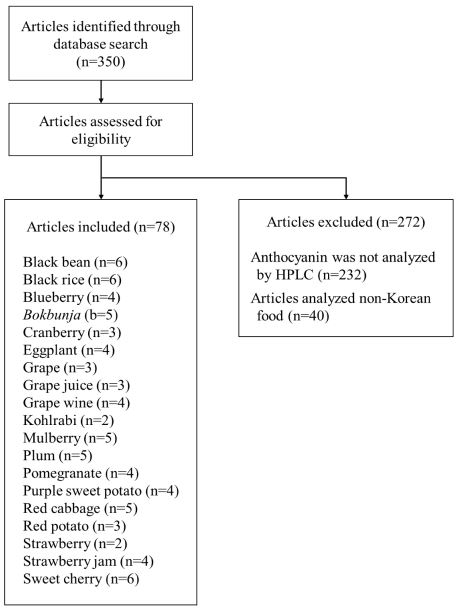

선정된 21종 식품의 안토시아닌 함량이 보고된 350편의 연구결과는 1997년부터 2017년에 발표되었다. 분광광도계를 이용하여 총 안토시아닌을 측정한 경우에는 특정 파장에서 흡광도를 이용하여 안토시아닌 함량이 추정될 수 있지만, 안토시아닌 이외의 색소에 의해 간섭이 일어날 수 있을 뿐만 아니라, 미세한 먼지 등의 불순물에 의해 빛이 산란되면 정확한 함량을 측정하기 어렵기 때문에 제외되었다. 본 연구에서는 액체크로마토그래피를 이용하여 개별 안토시아닌을 분리하고, 함량을 분석한 78편이 선별되어 식품별 안토시아닌 함량 범위가 도출되었다(Fig. 2).

안토시아닌이 존재한다고 보고된 식품군은 과일류, 곡류, 서류, 채소류이었다. 총 21종 식품 중에서 과일류가 9종(블루베리, 복분자, 크랜베리, 포도, 딸기, 버찌, 오디, 자두, 석류)으로 다수를 차지하였다. 딸기는 100% 자급률을 갖는 식품이므로 검색된 논문 25편에서 개별 안토시아닌을 분리하여 정량한 국내 논문 2편(Kim SK 등 2015; Lee H 2016)을 인용하였다. 딸기잼에 대한 국내 연구결과는 발색법을 이용하였기 때문에 국외 논문 4편(García-Viguera C 등 1997; García-Viguera C 등 1999; Koponen JM 등 2007; Kovačević DB 등 2015)을 인용하였다. 버찌, 석류, 자두, 크랜베리는 국내 연구가 부족하여 6편(Usenik V 등 2008; Mozetič B 등 2004; Ballistreri G 등 2013; Bastos C 등 2015; Toydemir G 등 2013; Dóka O 등 2011), 4편(Sengul H 등 2014; Mena P 등 2013; Zaouay F 등 2012; Cano-Lamadrid M 등 2017), 5편(Sahamishirazi 등 2017; Basanta MF 등 2016; Lestario LN 등 2017; Usenik V 등 2009; Wu X 등 2006), 3편(Zheng W & Wang SY 2003; Wu X 등 2006; Oszmiański J 등 2015)의 국외 연구결과를 참고하였다. 복분자와 오디는 대부분 국내에서 재배하기 때문에 각각 5편(Jun HI 등 2014; Lee SM 등 2012; Lee J 등 2013; Im SE 등 2013; Lee Y 등 2015), 5편(Song W 등 2009; Bae SH & Suh HJ 2007; Jun HI 등 2014; Lee Y & Hwang KT 2017; Lee Y 등 2015)의 국내 연구논문을 인용하였고, 블루베리는 국내 재배종(Vaccinium spp.)의 원산지가 북아메리카이므로 국내외 논문 15편 중 안토시아닌을 정성 및 정량한 4편(Kalt W 등 1999; Skrede G 등 2000; Wu X 등 2006; Koponen JM 등 2007)이 선별되었다. 포도의 국내 자급률은 99%이므로(Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs 2015) 국내 연구결과를 참고하는 것이 적절하다고 사료되었지만, 대부분의 국내 연구는 포도 껍질의 안토시아닌 함량 자료인 반면에, 국민건강영양조사의 식품섭취량은 포도의 과육을 포함한 수치이다. 따라서 포도 전체의 안토시아닌 함량을 보고한 3편(Kim HB 2003; Wu X 등 2006; Huang Z 등 2009)의 국내 및 국외 연구결과를 참고하여 안토시아닌 함량을 정리하였다. 포도주스와 포도주의 원재료에는 원산지가 대부분 수입으로 표기되어 있어서 각각 3편(Bub A 등 2001; Tiwari BK 등 2009; Bitsch R 등 2004), 4편(Suriano S 등 2016; Góa mez-Míaguez M & Heredia FJ 2004; Pellegrini N 등 2000; Sun B 등 2001)의 국외 연구결과를 인용하였다. 과일류 중 머루, 산딸기, 앵두, 오미자는 개별 안토시아닌을 분석한 자료가 검색되지 않아서 안토시아닌 함량 산출이 이루어지지 못했다.

검정콩, 자색감자, 자색고구마는 국내·외 논문이 6편(Tadeoka GR 등 1997; Wu X 등 2006; Xu B & Chang SKC 2009; Xu B & Chang SKC 2008a; Xu B & Chang SKC 2008b; Ranilla LGL 등 2007), 3편(Mulinacci N 등 2008; Li H 등 2012; Ieri F 등 2011), 4편(Zuh F 등 2010; Hong KH & Koh E 2016; Xu J 등 2015; Kim HW 등 2012)이 인용되었다. 흑미는 국내 자급률이 100%이었기 때문에(Kim T 등 2015) 국내 논문 6편(Lee JH 2010; Kim MK 등 2008; Ryu SN 등 1998; Kim JK 등 2010; Kim MJ 등 2007; Surh J & Koh E 2014)을 참고하였다. 채소류인 가지와 자색양배추는 안토시아닌 함량에 대한 국내 연구결과가 없어서 각각 4편(Li H 등 2012; Wu X 등 2006; Koponen JM 등 2007; Zhang Y 등 2014), 5편(Wu X 등 2006; Wiczkowski W 등 2013; Posmyk MM 등 2009; Li H 등 2012; Koponen JM 등 2007)의 국외 논문을 참고하였다. 콜라비는 개별 안토시아닌을 정량한 국외논문 2편(Zhang Y 등 2015; Park CH 등 2017)이 인용되었다. 하지만, 적겨자는 수집한 자료 중에서 개별 안토시아닌을 정량한 논문이 없어서 안토시아닌 총 섭취량을 산출할 수 없었다.

3. 식품별 안토시아닌 함량

자료검색에서 안토시아닌 함량이 도출되지 못한 식품 5종(머루, 산딸기, 앵두, 오미자, 적겨자)을 제외한 16종 식품의 안토시아닌 함량을 정리한 결과는 Table 1과 같다. 안토시아닌은 식물 내에서 기후, 재배 조건 등의 요인에 의해 자연적으로 생성되는 2차 대사산물이기 때문에, 동일한 품종이더라도 재배 지역에 따라 함량이 달라져(Connor AM 등 2002; Piccaglia R 등 2002; Lachman J 등 2012) 검색한 논문의 안토시아닌 함량의 범위가 넓게 나타났다. 생중량 100 g당 안토시아닌 함량이 높은 상위 5개 식품은 크랜베리(50∼4,009 mg), 자두(7∼1,318 mg), 복분자(7∼1,306 mg), 자색고구마(63∼807 mg), 오디(7∼562 mg)였으며, 하위 5개 식품은 딸기(5∼75 mg), 자색감자(24∼85 mg), 가지(6∼86 mg), 버찌(4∼145 mg), 자색양배추(34∼170 mg)로 나타났다. 곡류인 검정콩과 흑미는 생중량 100 g당 8∼558 mg, 5∼493 mg의 안토시아닌이 존재하였다. 채소류는 생중량 100 g 당 안토시아닌 함량이 콜라비 30∼302 mg, 자색양배추 34∼170 mg, 가지 6∼86 mg으로 다른 식품군에 비해 안토시아닌 함량이 적은 것으로 나타났다.

4. 식품 섭취량 산출

식품별 1일 섭취량이 많은 상위 5개 식품은 포도(8.87 g), 딸기(3.58 g), 포도주스(3.43 g), 검정콩(3.03 g), 자두(2.63 g)였으며, 하위 5개 식품은 복분자(0.09 g), 크랜베리(0.17 g), 오디(0.18 g), 자색양배추(0.24 g), 석류(0.25 g)로 나타났다(Table 1). 국민건강영양조사에 섭취량 자료가 없는 서류(자색고구마, 자색감자)를 제외하고, 식품군 별 섭취량을 비교해 보면, 과일류가 22.06 g으로 가장 높고, 곡류(4.78 g), 채소류(3.47 g) 순이었다.

5. 안토시아닌 섭취량

안토시아닌의 1일 섭취량을 산출한 결과, 자두 0.2∼34.7 mg/day, 포도 1.3∼15.1 mg/day, 검정콩 0.2∼16.9 mg/day, 흑미 0.1∼8.6 mg/day, 크랜베리 0.1∼6.8 mg/day, 블루베리 0.7∼3.1 mg/day, 딸기 0.2∼2.3 mg/day, 가지 0.2∼2.2 mg/day, 콜라비 0.2∼1.4 mg/day, 석류 0.0∼1.4 mg/day, 복분자 0.0∼1.2 mg/day, 머루 0.0∼1.0 mg/day, 버찌 0.0∼0.6 mg/day, 자색양배추 0.1∼0.4 mg/day 순이었다(Table 1). 안토시아닌 섭취량이 가장 많은 자두의 경우, 안토시아닌의 함량과 식품 섭취량 모두 상위 5개 식품 안에 포함되어 한국인의 안토시아닌 섭취량의 35%를 차지하였다. 자두를 제외한 안토시아닌 함량이 높은 복분자, 자색고구마, 오디는 식품 섭취량이 적거나, 자료가 없어 안토시아닌의 섭취량에 대한 기여도가 낮게 나타났다. 크랜베리는 식품 섭취량은 적지만 안토시아닌 함량이 많았기 때문에, 안토시아닌의 섭취량에 최대 7%까지 기여했다. 포도의 경우에는 안토시아닌 함량은 적었지만 식품 섭취량이 높아서 안토시아닌의 섭취량에 최대 14%까지 기여하였다. 곡류인 검정콩과 흑미는 안토시아닌 함량과 식품 섭취량이 높아 안토시아닌 섭취량에 기여하는 상위 5개 식품에 포함되었다. 안토시아닌 섭취량을 식품군별로 비교한 결과, 과일류 2.5∼66.0 mg, 곡류 0.3∼25.5 mg, 채소류 0.4∼4.0 mg으로 한국인의 식생활에서 안토시아닌의 급원식품군은 과일류와 곡류였다. 식품 중에서는 자두와 검정콩의 기여율이 높은 것으로 나타났다.

국가 별 안토시아닌 1일 섭취량을 비교해 보면, 미국인은 12.53 mg(Wu X 등 2006), 프랑스인은 57±47 mg(Pérez-Jiménez J 등 2011)으로 한국인의 1일 섭취량인 3.3∼95.5 mg과 비슷한 수준이었다. 나라 별 안토시아닌 주요 급원식품을 살펴보면, 미국인의 식생활에서는 블루베리와 포도였으며, 프랑스인의 경우에는 적포도주, 버찌, 딸기, 포도였다. 이는 한국인이 안토시아닌을 자두와 검정콩에서 주로 섭취하는 것과 차이를 보였다. 이러한 결과는 식생활 패턴에 따라 안토시아닌의 급원식품이 달라짐을 보여준다.

본 연구에서 도출된 안토시아닌 1일 섭취량은 식품섭취량과 안토시아닌 함량 자료가 존재하는 16종 식품에 한정되었으며, 조리과정에서의 안토시아닌 손실이 고려되지 않았다. 향후 연구에서는 안토시아닌 섭취량을 보다 정확하게 추정하기 위해 한국인이 섭취하는 대다수의 식품을 포괄할 뿐만 아니라, 조리과정에서의 안토시아닌 손실도 고려되어야 할 것이다. 무엇보다도 안토시아닌은 품종, 재배지역의 기후 및 토양 등에 의해 함량이 달라질 수 있으므로, 한국인이 섭취하는 식품의 안토시아닌 자료 확보가 반드시 필요하다.

요약 및 결론

본 연구는 한국인의 안토시아닌 총 섭취량을 추정하고, 주요 급원식품을 규명하였다. 안토시아닌 함량 자료가 존재하는 16종 식품(가지, 검정콩, 딸기, 버찌, 복분자, 블루베리, 석류, 오디, 자두, 자색감자, 자색고구마, 자색양배추, 콜라비, 크랜베리, 포도, 흑미)이 선별되었다. 16종의 식품의 안토시아닌 함량은 생중량 100 g 당 0∼4,009 mg의 범위였으며, 안토시아닌 함량이 많은 식품은 크랜베리, 자두, 복분자이었으며, 안토시아닌 함량이 적은 식품은 딸기, 자색감자, 가지였다. 식품별 1일 섭취량은 0.09∼8.87 g으로, 섭취량이 가장 많은 식품은 포도, 딸기, 포도주스였으며, 섭취량이 적은 식품은 복분자, 크랜베리, 오디로 나타났다. 16종 식품의 섭취를 통한 한국인의 안토시아닌 1일 섭취량은 3.3∼95.5 mg이었으며, 과일류, 곡류, 채소류로부터 각각 2.5∼66.0 mg, 0.3∼25.5 mg, 0.4∼4.0 mg의 안토시아닌을 섭취하는 것으로 나타났다. 식품별 기여도를 비교한 결과, 자두가 0.2∼34.7 mg으로 가장 높았으며, 검정콩, 포도 순으로 나타났다.

Acknowledgments

이 논문은 2017년도 정부(교육부)의 재원으로 한국연구재단의 지원을 받아 수행된 기초연구사업임(No. 2017R1D1A1-B03028841).

References

-

Anaga, A, Georgiev, V, Ochieng, J, Phills, B, Tsolova, V, (2013), Production of anthocyanins in grape cell cultures: A potential source of raw material for pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries, p247-287, In: The Mediterranean Genetic Code-grapevine and Olive Poljuha, D, Sladonja, B (eds.), InTech, Rijeka, Croatia.

[https://doi.org/10.5772/54592]

-

Bae, SH, Suh, HJ, (2007), Antioxidant activities of five different mulberry cultivars in Korea, LWT, 40, p955-962.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2006.06.007]

-

Ballistreri, G, Continella, A, Gentile, A, Amenta, M, Fabroni, S, Rapisarda, P, (2013), Fruit quality and bioactive compounds relevant to human health of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) cultivars grown in Italy, Food Chem, 140, p630-638.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.024]

-

Basanta, MF, Marin, A, De Leo, SA, Gerschenson, LN, Erlejan, AG, Tomás-Barberán, FA, Rojas, AM, (2016), Antioxidant Japanese plum (Prunus salicina) microparticles with potential for food preservation, J Funct Foods, 24, p287-296.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2016.04.015]

-

Bastos, C, Barros, L, Dueñas, M, Calhelha, RC, Queiroz, MJRP, Santos-Buelga, S, Ferreira, ICFR, (2015), Chemical characterisation and bioactive properties of Prunus avium L.: The widely studied fruits and the unexplored stems, Food Chem, 173, p1045-1053.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.10.145]

- Bitsch, R, Netzel, M, Frank, T, Strass, G, Bitsch, I, (2004), Bioavailability and biokinetics of anthocyanins from red grape juice and red wine, J Biomed Biotechnol, 5, p293-298.

-

Bub, A, Watzl, B, Heeb, D, Rechkemmer, G, Briviba, K, (2001), Malvidin-3-glucoside bioavailability in humans after ingestion of red wine, dealcoholized red wine and red grape juice, Eur Nutr, 40, p113-120.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s003940170011]

-

Cabrita, L, Fossen, T, Andersen, ØM, (2000), Colour and stability of the six common anthocyanin 3-glucosides in aqueous solutions, Food Chem, 68, p101-107.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0308-8146(99)00170-3]

-

Cano-Lamadrid, M, Lech, K, Michalska, A, Wasilewska, W, Figiel, A, Wojdyło, A, Carbonell-Barrachina, ÁA, (2017), Influence of osmotic dehydration pre-treatment and combined drying method on physico-chemical and sensory properties of pomegranate arils, cultivar Mollar de Elche, Food Chem, 232, p306-315.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.04.033]

-

Cevallos-Casals, BA, Cisneros-Zevallos, L, (2004), Stability of anthocyanin-based aqueous extracts of Andean purple corn and red-fleshed sweet potato compared to synthetic and natural colorants, Food Chem, 86, p69-77.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.08.011]

- Chung, KW, Joo, YH, Lee, DJ, (2004), Content and color different of anthocyanin by different storage periods in seed coats of black soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.), Korean J Agri, 16(2), p196-199.

-

Connor, AM, Luby, JJ, Hancock, JF, Berkheimer, S, Hanson, EJ, (2002), Changes in fruit antioxidant activity among blueberry cultivars during cold-temperature storage, J Agric Food Chem, 50(4), p893-898.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf011212y]

- Dóka, O, Ficzek, G, Bicanic, D, Spruijt, R, Luterotti, S, Tóth, M, Buijnsters, JG, Végvári, G, (2011), Direct photothermal techniques for rapid quantification of total anthocyanin content in sour cherry cultivars, Talanta, 84, p341-346.

-

Francis, FJ, Markakis, PC, (1989), Food colorants: Anthocyanins, Criti Rev Food Sci Nutr, 28(4), p273-314.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398909527503]

- García-Viguera, C, Zafrilla, P, Romero, F, Abellán, P, Artés, F, Tomás-Barberán, FA, (1999), Color stability of strawberry jam as affected by cultivar and storage temperature, J Food Sci, 64(2), p243-247.

- García a-Viguera, C, Zafrilla, P, Tomás-Barberán, FA, (1997), Determination of authenticity of fruit Jams by HPLC analysis of anthocyanins, J Sci Food Agric, 73, p207-213.

-

Giusti, MM, Wrolstad, RE, (2003), Acylated anthocyanins from edible sources and their applications in food systems, Biochem Eng J, 14, p217-225.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s1369-703x(02)00221-8]

- Góa mez-Míaguez, M, Heredia, FJ, (2004), Effect of the maceration technique on the relationships between anthocyanin composition and objective color of Syrah wines, J Agric Food Chem, 52, p5117-5123.

-

He, J, Giusti, MM, (2010), Anthocyanins: Natural colorants with health-promoting properties, Annu Rev Food Sci Technol, 1(3), p163-187.

[https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.food.080708.100754]

-

Hong, KH, Koh, E, (2016), Effects of cooking methods on anthocyanins and total phenolics in purple-fleshed sweet potato, J Food Process Preserv, 40, p1054-1063.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.12686]

-

Hribar, U, Ulrih, NP, (2014), The metabolism of anthocyanins, Curr Drug Metab, 15(1), p3-13.

[https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200214666131211160308]

-

Huang, Z, Wang, B, Williams, P, Pace, RD, (2009), Identification of anthocyanins in muscadine grapes with HPLC-ESI-MS, Food Sci Technol, 42, p819-824.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2008.11.005]

-

Ieri, F, Innocenti, M, Andrenelli, L, Vecchio, V, Mulinacci, N, (2011), Rapid HPLC/DAD/MS method to determine phenolic acids, glycoalkaloids and anthocyanins in pigmented potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) and correlations with variety and geographical origin, Food Chem, 125, p750-759.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.09.009]

-

Im, SE, Nam, TG, Lee, H, Han, MW, Heo, HJ, Koo, SI, Lee, CY, Kim, DO, (2013), Anthocyanins in the ripe fruits of Rubus coreanus Miquel and their protective effect on neuronal PC-12 cells, Food Chem, 139, p604-610.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.12.057]

-

Joo, SY, Choi, HY, (2012), Antioxidant activity and quality characteristics of black rice bran cookies, J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr, 41(2), p182-191.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2012.41.2.182]

-

Jun, HI, Kim, YA, Kim, YS, (2014), Antioxidant activities of Rubus coreanus Miquel and Morus alba L. fruits, J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr, 43(3), p381-388.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2014.43.3.381]

-

Kalt, W, McDonald, JE, Ricker, RD, Lu, X, (1999), Anthocyanin content and profile within and among blueberry species, Can J Plant Sci, 79, p617-623.

[https://doi.org/10.4141/p99-009]

- Kim, HB, (2003), Quantification of cyanidin-3-glucoside (C3G) in mulberry fruits and grapes, Korean J Seric Sci, 45(1), p1-5.

-

Kim, HW, Kim, JB, Cho, SM, Chung, MN, Lee, YM, Chu, SM, Che, JH, Kim, SN, Kim, SY, Cho, YS, Kim, JH, Park, HJ, Lee, DJ, (2012), Anthocyanin changes in the Korean purplefleshed sweet potato, Shinzami, as affected by steaming and baking, Food Chem, 130, p966-972.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.08.031]

-

Kim, JK, Lee, SY, Chu, SM, Lim, SH, Suh, SC, Lee, YT, Cho, HS, Ha, SH, (2010), Variation and correlation analysis of flavonoids and carotenoids in Korean pigmented rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars, J Agric Food Chem, 58(24), p12804-12809.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf103277g]

-

Kim, MJ, Hyun, JN, Kim, JA, Park, JC, Kim, MY, Kim, JG, Lee, SJ, Chun, SC, Chung, IM, (2007), Relationship between phenolic compounds, anthocyanins content and antioxidant activity in colored barley germplasm, J Agric Food Chem, 55, p4802-4809.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0701943]

-

Kim, MK, Kim, HA, Koh, K, Kim, HS, Lee, YS, Kim, YH, (2008), Identification and quantification of anthocyanin pigments in colored rice, Nutr Res Pract, 2(1), p46-49.

[https://doi.org/10.4162/nrp.2008.2.1.46]

-

Kim, SK, Kim, DS, Kim, DY, Chun, C, (2015), Variation of bioactive compounds content of 14 oriental strawberry cultivars, Food Chem, 184, p196-202.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.03.060]

- Kim, T, Park, D, Son, M, Lee, D, (2015), A study on the midlongterm direction of grain policy: Focusing on Korea’s rice trade policy (year 2 of 1), Korea Rural Economic Institute, Naju, Korea, p91.

-

Kong, JM, Chia, LS, Goh, NK, Chia, TF, Brouillard, R, (2003), Analysis and biological activities of anthocyanins, Phytochemistry, 64(5), p923-933.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9422(03)00438-2]

-

Koponen, JM, Happonen, AM, Mattila, PH, Törrönen, AR, (2007), Content of anthocyanins and ellagitannins in selected foods consumed in Finland, J Agric Food Chem, 55, p1612-1619.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf062897a]

- Korea Health Industry Development Institute, (2016), National food & nutrition statistics Ⅰ: based on 2014 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, KHIDI, Osong, Korea, p15-70.

- Kovačević, DB, Putnik, P, Dragović-Uzelac, V, Vahčić, Babojelić, MS, Levaj, B, (2015), Influences of organically and conventionally grown strawberry cultivars on anthocyanins content and color in purees and low-sugar jams, Food Chem, 181, p94-100.

- Lachman, J, Hamouz, K, Orsák, M, Pivec, V, Hejtmánková, K, Pazderů, K, Dvořák, P, Čepl, J, (2012), Impact of selected factors-cultivar, storage, cooking and baking on the content anthocyanins in coloured-flesh potatoes, Food Chem, 133, p1107-1116.

- Lee, H, (2016), Introduction of pigmentation and anthocyanin biosynthesis in harvested strawberry fruit by methyl jasmonate, MS Thesis Seoul National Universit, Seoul, p28-34.

-

Lee, J, Dossett, M, Finn, CE, (2013), Anthocyanin fingerprinting of true bokbunja (Rubus coreanus Miq.) fruit, J Funct Foods, 5, p1985-1990.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2013.06.006]

-

Lee, JH, (2010), Identification and quantification of anthocyanins from the grains of black rice (Oryza sativa L.) varieties, Food Sci Biotechnol, 19(2), p391-397.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10068-010-0055-5]

-

Lee, MK, Kim, HW, Lee, SH, Kim, YJ, Jang, HH, Jung, HA, Hwang, YJ, Choe, JS, Kim, JB, (2016), Compositions and contents anthocyanins in blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) varieties, Korean J Environ Agric, 35(3), p184-190.

[https://doi.org/10.5338/kjea.2016.35.3.25]

-

Lee, SM, You, Y, Kim, K, Park, J, Jeong, C, Jhon, DY, Jun, W, (2012), Antioxidant activities of native Gwangyang Rubus coreanus Miq, J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr, 41(3), p327-332.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2012.41.3.327]

- Lee, Y, Hwang, KT, (2017), Changes in phytochemical properties of mulberry fruits (Morus alba L.) during ripening, Sci Hort, 217, p189-196.

-

Lee, Y, Lee, JH, Kim, SD, Chang, MS, Jo, IS, Kim, SJ, Hwang, KT, Jo, HB, Kim, JH, (2015), Chemical composition, functional constituents, and antioxidant activities of berry fruits produced in Koera, J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr, 44(9), p1295-1303.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2015.44.9.1295]

-

Lestario, LN, Howard, LR, Brownmiller, C, Stebbins, NB, Liyanage, R, Lay, JO, (2017), Changes in polyphenolics during maturation of Java plum (Syzygium cumini Lam.), Food Res Int in press.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2017.04.023]

-

Li, H, Deng, Z, Zhu, H, Hu, C, Liu, R, Young, JC, Tsao, R, (2012), Highly pigmented vegetables: Anthocyanin compositions and their role in antioxidant activities, Food Res Int, 46, p250-259.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2011.12.014]

-

Liu, YN, Jeong, DH, Jung, JH, Kim, HS, (2013), Quality characteristics and antioxidant activities of cookies added with purple sweet potato powder, Korean J Food Cookery Sci, 29(3), p275-281.

[https://doi.org/10.9724/kfcs.2013.29.3.275]

-

Mena, P, Vegara, S, Martí, N, Carcía-Viguera, C, Saura, D, Valero, M, (2013), Changes on indigenous microbiota, colour, bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of pasteurised pomegranate juice, Food Chem, 141, p2122-2129.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.04.118]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, (2015), Utilization rate of imported foods, http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=114&tblId=DT_114_2015_S0003 Accessed June 13, 2017.

- Mozetič, B, Trebše, P, Simčič, M, Hribar, J, (2004), Changes of anthocyanins and hydroxycinnamic acids affecting the skin colour during maturation of sweet cherries (Prunus avinum L.), LWT, 37, p123-128.

- Mulinacci, N, Ieri, F, Giaccherini, C, Innocenti, M, Andrenelli, L, Canova, G, Saracchi, M, Casiraghi, MC, (2008), Effect of cooking on the anthocyanins, phenolic acids, glycoalkaloids, and resistant starch content in two pigmented cultivars of Solanum tuberosum L, J Agric Food Chem, 556, p11830-11837.

-

Nabavi, SF, Habtemariam, S, Daglia, M, Shafighi, N, Barber, AJ, Nabavi, SM, (2015), Anthocyanins as a potential therapy for diabetic retinopathy, Curr Med Chem, 22(1), p51-58.

[https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867321666140815123852]

- Oszmiański, J, Kolniak-Ostek, J, Lachowicz, S, Gorzelany, J, Matłok, N, (2015), Effect of dried powder preparation process on polyphenolic content and antioxidant capacity of cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon L.), Ind Crops Prod, 77, p658-665.

-

Park, CH, Yeo, HJ, Kim, NS, Eun, PY, Kim, SJ, Arasu, MV, Al-Dhabi, NA, Park, SY, Kim, JK, Park, SU, (2017), Metabolic profiling of pale green and purple kohlrabi (Brassica oleracea var. gongylodes), Appl Biol Chem, 60(3), p249-257.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s13765-017-0274-z]

-

Pellegrini, N, Simonetti, P, Gardana, C, Brenna, O, Brighenti, F, Pietta, P, (2000), Polyphenol content and total antioxidant activity of Vini novelli (young red wines), J Agric Food Chem, 48, p732-735.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf990251v]

- Pérez-Jiménez, J, Fezeu, L, Touvier, M, Arnault, N, Manach, C, Hercberg, S, Galan, P, Scalbert, A, (2011), Dietary intake of 337 polyphenols in French adults, Am J Clin Nutr, 93, p1220-1228.

- Piccaglia, R, Marotti, M, Baldoni, G, (2002), Factors influencing anthocyanin content in red cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata L frubra (L) Thell), J Sci Food Agric, 82, p1504-1509.

-

Posmyk, MM, Janas, KM, Kontek, R, (2009), Red cabbage anthocyanin extract alleviates copper-induced cytological disturbances in plant meristematic tissue and human lymphocytes, Biometals, 22, p479-490.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-009-9205-8]

-

Ranilla, LG, Genovese, MI, Lajolo, FM, (2007), Polyphenols and antioxidant capacity of seed coat and cotyledon from Brazilian and Peruvian bean cultivars (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), J Agric Food Chem, 55, p90-98.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf062785j]

- Rural Development Administration/National Institute Agricultural Sciences, (2011), 8th Revision Food Composition Table, Suwon, Korea, p28-206.

- Ryu, SN, Park, SZ, Ho, CT, (1998), High performance liquid chromatographic determination of anthocyanin pigments in some varieties of black rice, J Food Drug Anal, 6(4), p729-736.

-

Sahamishirazi, S, Moehring, J, Claupein, W, Graeff-Hoenninger, S, (2017), Quality assessment of 178 cultivars of plum regarding phenolic, anthocyanin and sugar content, Food Chem, 214, p694-701.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.070]

-

Sengul, H, Surek, E, Nilufer-Erdil, D, (2014), Investigating the effects of food matrix and food components on bioaccessibility of pomegranate (Punica granatum) phenolics and anthocyanins using an in-vitro gastrointestinal digestion model, Food Res Int, 62, p1069-1079.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2014.05.055]

-

Skrede, G, Wrolstad, RE, Durst, RW, (2000), Changes in anthocyanins and polyphenolics during juice processing of highbush blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum L.), J Food Sci, 65(2), p357-364.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2000.tb16007.x]

-

Song, W, Wang, HJ, Bucheli, P, Zhang, PF, Wei, DZ, Lu, YH, (2009), Phytochemical profiles of different mulberry (Morus sp.) species from China, J Agric Food Chem, 57, p9133-9140.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf9022228]

-

Sun, B, Spranger, I, Roque-do-Vale, F, Leandro, C, Belchior, P, (2001), Effect of different winemaking technologies on phenolic composition in Tinta Miúda red wines, J Agric Food Chem, 49, p5809-5816.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf010661v]

-

Surh, J, Koh, E, (2014), Effects of four different cooking methods on anthocyanins, total phenolics and antioxidant activity of black rice, J Sci Food Agric, 94, p3296-3304.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.6690]

-

Suriano, S, Alba, V, Gennaro, DD, Suriano, MS, Savino, M, Tarricone, L, (2016), Genotype/rootstocks effect on the expression of anthocyanins and flavans in grapes and wines of Greco Nero n. (Vitis vinifera L.), Sci Hort, 209, p309-315.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2016.07.004]

- Takeoka, GR, Dao, LT, Full, GH, Wong, RY, Harden, LA, Edwards, RH, Berrios, JDJ, (1997), Characterization of black bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) anthocyanins, J Agric Food Chem, 45(9), p3395-3400.

-

Tiwari, BK, O’Donnell, CP, Patras, A, Brunton, N, Cullen, PJ, (2009), Anthocyanins and color degradation in ozonated grape juice, Food Chem Toxicol, 47, p2824-2829.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2009.09.001]

-

Toydemir, G, Capanoglu, E, Roldan, MVG, de Vos, RCH, Boyacioglu, D, Hall, RD, Beekwilder, J, (2013), Industrial processing effects on phenolic compounds in sour cherry (Prunus cerasus L.) fruit, Food Res Int, 53, p218-225.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2013.04.009]

-

Usenik, V, Fabčič, J, Štampar, F, (2008), Sugar, organic acids, phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.), Food Chem, 107, p185-192.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.08.004]

- Usenik, V, Štampar, F, Veberič, R, (2009), Anthocyanins and fruit colour in plums (Prunus domestica L.) during ripenging, Food Chem, 2009, p529-534.

-

Wiczkowski, W, Szawara-Nowak, D, Topolska, J, (2013), Red cabbage anthocyanins: Profile, isolation, identification, and antioxidant activity, Food Res Int, 51, p303-309.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2012.12.015]

-

Winkel-Shirley, B, (2001), Flavonoid biosynthesis: A colorful model for genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, and biotechnology, Plant Physiol, 126(2), p485-493.

[https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.126.2.485]

- Wu, B, Chang, SKC, (2008a), Antioxidant capacity of seed coat, dehulled bean, and whole black soybeans in relation to their distributions of total phenolics, phenolic acids, anthocyanins, and isoflavones, J Agric Food Chem, 56, p8365-8373.

- Wu, B, Chang, SKC, (2008b), Total phenolics, phenolic acids, isoflavones, and anthocyanins and antioxidant properties of yellow and black soybean as affected by thermal processing, J Agric Food Chem, 56, p7165-7175.

- Wu, B, Chang, SKC, (2009), Total phenolic, phenolic acid, anthocyanin, flavan-3-ol, and flavonol profiles and antioxidant properties of pinto and black beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) as affected by thermal processing, J Agric Food Chem, 57, p4754-4764.

-

Wu, X, Beecher, GR, Holden, JM, Haytowitz, DB, Gebhardt, SE, Prior, RL, (2006), Concentrations of anthocyanins in common foods in the United States and estimation of normal consumption, Food Chem, 54, p4069-4075.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf060300l]

-

Xu, J, Su, X, Lim, S, Griffin, J, Carey, E, Katz, B, Tomich, J, Smith, JS, Wang, W, (2015), Characterisation and stability of anthocyanins in purple-fleshed sweet potato P40, Food Chem, 186, p90-96.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.08.123]

-

Yoshimoto, M, Okuno, S, Yamaguchi, M, Yamakawa, O, (2001), Antimutagenicity of deacylated anthocyanins in purplefleshed sweetpotato, Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 65(7), p1652-1655.

[https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.65.1652]

-

Zaouay, F, Mena, P, Garcia-Viguera, C, Mars, M, (2012), Antioxidant activity and physico-chemical properties of Tunisian grown pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) cultivars, Ind Crops Prod, 40, p81-89.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.02.045]

-

Zhang, Y, Hu, Z, Chu, G, Huang, C, Tian, S, Zhao, Z, Chen, G, (2014), Anthocyanin accumulation and molecular analysis of anthocyanin biosynthesis-associated genes in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.), J Agric Food Chem, 62, p2906-2912.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf404574c]

- Zhang, Y, Hu, Z, Zhu, M, Zhu, Z, Wang, Z, Tian, S, Chem, G, (2015), Anthocyanin accumulation and molecular analysis of correlated genes in purple kohlrabi (Brassica oleracea var. gongylodes L.), J Agric Food Chem, 63(16), p4160-4169.

-

Zhao, CL, Yu, YQ, Chen, ZJ, Wen, GS, Wei, FG, Zheng, Q, Wang, CD, Xiao, XL, (2017), Stability-increasing effects of anthocyanin glycosyl acylation, Food Chem, 214, p119-128.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.07.073]

-

Zheng, W, Wang, SY, (2003), Oxygen radical absorbing capacity of phenolics in blueberries, cranberries, chokeberries, and lingonberries, J Agric Food Chem, 51, p502-509.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf020728u]

-

Zhu, F, Cai, YZ, Yang, X, Ke, J, Korke, H, (2010), Anthocyanins, hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives, and antioxidant activity in roots of different Chinese purple-fleshed sweetpotato genotypes, J Agric Food Chem, 58, p7588-7596.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/jf101867t]