로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎을 이용한 혼합차 개발

Abstract

This study was designed to optimize the mixing ratio of roasted mulberry and peppermint leaves to enhance the physicochemical properties of the blend using RSM (response surface methodology). The roasted mulberry leaf (X1) and the roasted peppermint leaf (X2) were independent variables, and antioxidant activity (Y1) and α-glucosidase inhibitory effect (Y2) were dependent variables. The antioxidant activity and α-glucosidase inhibitory effect was maximum when the mixing ratio of the roasted mulberry leaf to the roasted peppermint leaf was 0.53 : 0.75. At this ratio, the total polyphenol content was 46.37 mg TAE/g, the total flavonoid content was 37.24 mg QE/g, DPPH radical scavenging activity was 71.44%, ABTS radical scavenging activity was 37.66% and α-glucosidase inhibitory effect was 53.59%. In conclusion, this study successfully derived the optimal ratio for a blend of roasted mulberry and peppermint leaves, at which the antioxidant activity and α-glucosidase inhibitory effect were maximal.

Keywords:

RSM, roasting, tea, mulberry leaf, peppermint leaf서 론

경제 발전과 식생활의 서구화로 인한 생활습관의 변화는 다양한 만성질환 발생의 주요 원인이 되고 있다(WHO 2003). 세계보건기구(WHO)에서는 2016년을 기준으로 만성질환으로 인한 사망률이 전 세계 사망원인의 70%를 차지하고 있다고 보고하였다(WHO 2018). 이러한 만성질환들 중 당뇨병의 경우 음주나 흡연뿐만 아니라, 체중조절과 식이요법이 당뇨병 유병률에 영향을 미치는 요인으로 나타났다(Hong JY & Park JA 2014). WHO에서도 균형 잡힌 식생활과 적절한 운동이 포함된 올바른 생활습관을 통해 당뇨병을 포함한 다양한 만성질환을 경감시킬 것을 권장하고 있다(WHO 2018).

최근 식생활과 만성질환의 관련성이 밝혀지면서 생체조절 기능을 지닌 천연물탐색 연구가 활발히 진행되고 있다(Shin KS 2012).

그 가운데 뽕잎(Morus alba L.)은 모세혈관 강화성분인 rutin, 혈압 강하성분인 GABA(γ-aminobutyric acid), 혈당 강하성분인 DNJ(1-deoxynojirimycin)를 풍부하게 함유하고 있다(Chae JY 등 2003). 또한, 뽕잎은 citric acid, lactic acid 등의 유기산, histidine, leucine 등의 유리아미노산, 무기질과 bezenemethanol 등의 휘발성 성분도 함유하고 있다(Kim JS 2009). 이러한 뽕잎에 함유된 기능성 물질의 항산화 및 항당뇨 활성(Hunyadi A 등 2012), HDL-콜레스테롤 증가, 총 콜레스테롤 저하, LDL-콜레스테롤 저하 등 심혈관 질환에 대한 효과 등이 규명되어 있다(Shim JU 등 2008).

페퍼민트 잎(Mentha piperita L.)은 menthol, menthone, limonene, cineole 등(Saleem A 등 2019)과 rutin, catechin hydrate, quercetin, chlorogenic acid 등의 기능성 성분을 다양하게 함유하고 있다(Augšpole I 등 2018). 이러한 성분 때문에 페퍼민트 잎에서 추출한 essential oil은 항산화, 항균, 항바이러스 등의 생리활성 효과가 있는 것으로 보고되었다(Loolaie M 등 2017). 페퍼민트 추출물을 알록산(alloxan)으로 당뇨병을 유도한 쥐에게 21일 동안 경구 투여한 결과, 혈당 수치가 감소하는 결과가 나타났다(Sailesh KS & Padamanabha 2014). 또한 Barbalho SM 등(2011)의 연구에서 25명의 대학생을 대상으로 30일 동안 매일 두 번씩 페퍼민트 주스를 섭취하게 한 결과, 대상자의 41.5%가 혈당이 낮아졌으며, 약 70%의 대상자에게서 GOT와 GPT 수치가 낮아지는 결과가 나타났다.

차(tea) 제조 시 로스팅(roasting) 과정에서 고분자물질이 저분자화 되면서 휘발성 물질과 polyphenol성 생리활성 물질의 함량이 증가하게 된다(Kim DC 등 2010). 또한, 맛 성분의 생성과 함께 쓴맛이나 떫은맛이 감소되는 효과도 있다. 따라서 로스팅은 차 제조 시 차의 품질을 결정하는 매우 중요한 과정이다(Lee KH 등 2014).

차는 전 세계적으로 두터운 소비층을 확보하고 있는 음료로, 우리나라에서도 2017년 생산액 기준으로 액상차(61.0%), 침출차(21.6%), 고형차(17.4%) 순으로 많이 소비되고 있다. 최근에는 블랜딩 티와 같은 다류 제품과 기능성이 강화된 프리미엄 차에 대한 소비자 니즈가 높아지고 있는 추세다(KAFFTC 2019).

따라서 본 연구에서는 항산화 활성과 항당뇨 효과가 이미 규명되어 있는 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 효능을 로스팅 처리를 통해 강화시킨 후 RSM을 이용하여 최적 혼합비율을 구해 기능성 혼합차를 개발하고자 하였다.

연구방법

1. 실험재료

본 실험에 사용된 뽕잎은 단야농장(Gimje, Korea)에서 2019년 6월 중순에 채취된 것을 구입하였으며, 페퍼민트 잎은 대구허브농장(Daegu, Korea)에서 2019년 6월 중순에 채취된 것을 구입하여 시료로 사용하였다.

2. 로스팅 처리

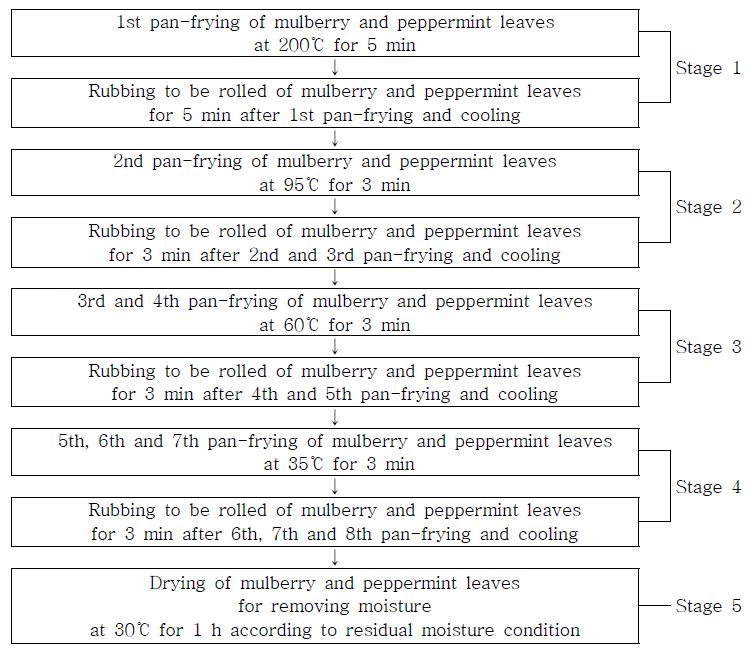

뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 로스팅 처리는 Kim AJ 등(2016)의 방법을 일부 변형하여 진행하였다(Fig. 1). 즉, 1단계에서는 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 각각 150 g씩을 200℃ 온도의 팬(HP-331, Dongyangmagic, Seoul, Korea)에 넣고 5분간 로스팅, 5분간 유념, 실온에서 식히는 과정 순서대로 1회 수행하였다. 2단계에서는 95℃의 팬에서 3분간 로스팅, 3분간 유념, 실온에서 식히는 과정 순서대로 1회 수행하였다. 3단계에서는 60℃의 팬에서 2단계 과정을 2회 반복하였다. 4단계에서는 35℃의 팬에서 2단계 과정을 3회 반복하였다. 5단계에서는 잔여 수분을 제거하기 위해 30℃의 팬에서 1시간 동안 건조시켰다. 완성된 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎은 4℃ 냉장고에 보관하면서 시료로 사용하였다.

3. 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 추출물의 생리활성

200 mL 컵에 60℃와 80℃로 온도를 맞춘 물을 100 mL씩 넣고 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎을 각각 1.5 g씩 넣고 3분간 우려내어 시료로 사용하였다. RSM을 이용한 11개의 혼합차 시료들(Table 1)은 각각 500 mL 컵에 80℃로 맞춘 물 200 mL씩 넣고 3분간 우려내어 생리활성 측정용 시료로 사용하였다. Joo SJ 등(2002)의 연구에서 다양한 허브를 60℃와 80℃ 그리고 100℃로 나누어 침출하였는데, 민트의 경우는 저온에서 침출하는 것이 보다 효과적으로 나타났다. 이에 본 연구에서는 60℃와 80℃로 추출온도를 설정하였다.

Total polyphenol 함량은 F-C 시약을 사용하는 Singleton VL & Rossi JA(1965)의 방법을 변형하여 측정하였다. 시료 350 μL에 50% Folin-Denis 시약 70 μL를 가하여 3분간 정치한 후, 2%(w/v) Na2CO3 용액 350 μL를 첨가하여 1시간 반응시킨 후 ELISA microplate reader(Infinite M200 pro, Männedorf Switzerland)를 이용하여 750 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. Total polyphenol 함량은 tannic acid를 이용하여 작성한 표준곡선으로부터 구하였다.

Total flavonoid 함량은 Davis WB(1947)의 방법을 변형하여 측정하였다. 시료 70 μL에 diethylene glycol 700 μL를 첨가하고 다시 1 N NaOH 용액 7 μL를 첨가한 후 37℃에서 1시간 반응시킨 후 ELISA reader를 이용하여 420 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다. Total flavonoid 함량은 quercetin을 이용하여 작성한 표준곡선으로부터 구하였다.

DPPH(1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhy drazyl; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) radical 소거능은 Blois MS(1958)의 방법을 변형하여 측정하였다. 시료 100 μL에 1.5 × 10-4 M DPPH 용액 100 μL를 가하여 실온의 암실에서 30분간 정치한 후 ELISA reader를 이용하여 517 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다.

ABTS(2,2'-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzo-thiazoline-6-sulfonic acid; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) radical 소거능은 Fellegrini N 등(1999)의 방법을 변형하여 측정하였다.

ABTS 7.4 mM과 potassium persulphate 2.6 mM을 같은 비율로 섞어 하루 동안 암소에 방치하여 ABTS 양이온을 형성시킨 후 732 nm에서 흡광도 값이 0.70±0.02가 되도록 1×PBS로 희석하였다. 희석된 ABTS 용액 190 μL에 추출물 시료 10 μL를 가하여 10분간 정치한 후 ELISA reader를 이용하여 732 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하였다.

α-Glucosidase 저해 활성은 Li T 등(2005)의 방법을 변형하여 측정하였다.

각각의 well에 시료 50 μL와 100 mM phosphate buffer(pH 6.8) 90 μL를 넣은 후 10 mM phosphate buffer에 0.2 unit/mL 농도로 녹인 α-glucosidase 20 μL를 넣고 37℃에서 15분 동안 preheating 시켰다. 기질로 사용된 2.5 mM 4-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside(PNPG)는 100 mM phosphate buffer에 녹여 40 μL를 첨가하여 37℃에서 25분간 반응시킨 후 ELISA reader를 이용하여 405 nm에서 흡광도를 측정한 후 공식을 이용하여 저해율을 산출하였다.

4. RSM을 이용한 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 최적 혼합비율 설정

로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 최적 혼합 비율을 도출하기 위한 실험설계는 Design Expert 10(Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) 프로그램을 사용하였으며, 반응표면분석법(RSM: Response Surface Methodology)의 중심합성 계획법 설계에 따라 11개의 실험점을 설정하였다.

독립변수는 로스팅 뽕잎(X1)과 페퍼민트 잎(X2)의 함량으로 하였고, 예비 실험을 거쳐 로스팅 뽕잎(X1)의 최소 및 최대 범위는 0.50∼1.50으로 결정하였으며, 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎(X2)의 최소 및 최대 범위는 0.25∼0.75로 결정하였다.

종속변수는 total polyphenol 함량, total flavonoid 함량, DPPH radical 소거능, ABTS radical 소거능, α-glucosidase 저해 활성으로 설정하였다. 실험설계에 따른 실험점은 Table 1에 제시된 바와 같다.

5. 통계처리

실험 자료 분석과 최적화는 Design Expert 10(Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA)을 이용하였고, 이외 모든 자료는 SPSS statistics 24(SPSS Institute, Chicago, IL, USA)를 이용하여 표준편차와 평균을 구하여 통계 분석을 실시하였다.

독립변수 요인이 3개 이상인 경우에 one-way ANOVA를 실시하였으며, Duncan’s multiple range test로 각 시료 평균 차이에 대한 사후 검정을 유의 수준 5%에서 실시하였다.

결과 및 고찰

1. 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 항산화 활성

로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎을 온도별(60℃, 80℃)로 추출 후 total polyphenol, total flavonoid 함량과 DPPH radical, ABTS radical 소거능을 분석하여 Table 2와 Table 3에 각각 제시하였다.

Total polyphenol content and total flavonoid content of roasted mulberry and peppermint leaves by temperature (60℃ and 80℃)

DPPH radical scavenging activity and ABTS radical scavenging activity of roasted mulberry and peppermint leaves by temperature (60℃ and 80℃)

로스팅 뽕잎을 60℃와 80℃에서 추출한 시료들의 total polyphenol 함량은 52.06∼57.81 mg TAE/g의 범위로 나타났으며, total flavonoid 함량은 245.36∼414.39 mg QE/g의 범위로 나타났다. Total polyphenol 함량과 total flavonoid 함량 모두 80℃에서 추출한 시료(RoML80)가 활성이 가장 높게 나타났다.

로스팅 페퍼민트 잎을 60℃와 80℃에서 추출한 시료들의 total polyphenol 함량 범위는 63.02∼64.10 mg TAE/g으로 나타났으며, total flavonoid 함량은 600.72∼774.00 mg QE/g의 범위로 나타났다. Total polyphenol 함량과 total flavonoid 함량 모두 80℃에서 추출한 시료(RoPL80)가 활성이 가장 높게 나타났다.

로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 모두 80℃에서 추출한 시료에서 total polyphenol 함량과 total flavonoid 함량이 높게 나타났으며, 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎이 로스팅 뽕잎보다 total polyphenol 함량과 total flavonoid 함량이 높았다. 이는 Yoo SM(2019)의 연구에서 페퍼민트차의 total polyphenol 함량이 뽕잎차보다 더 높았던 것과 Hwang AR(2019)의 연구에서 페퍼민트차의 total flavonoid 함량이 뽕잎차보다 더 높았던 것과 일치하는 결과이다.

로스팅 뽕잎을 60℃와 80℃에서 추출한 시료들의 DPPH radical 소거능은 각각 73.33∼73.97%의 범위로 나타났으며, ABTS radical 소거능은 22.63∼34.74%의 범위로 나타났다. DPPH radical 소거능과 ABTS radical 소거능 모두 80℃에서 추출한 시료(RoML80)에서 활성이 가장 높게 나타났다.

로스팅 페퍼민트 잎을 60℃와 80℃에서 추출한 시료들의 DPPH radical 소거능은 72.87∼75.19%의 범위로 나타났으며, ABTS radical 소거능은 87.36∼93.50%의 범위로 나타났다. DPPH radical 소거능과 ABTS radical 소거능 모두 80℃에서 추출한 시료(RoPL80)에서 활성이 가장 높게 나타났다.

로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 모두 80℃에서 추출했을 때 DPPH radical 소거능과 ABTS radical 소거능이 높게 나타났으며, 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎이 로스팅 뽕잎보다 DPPH radical 소거능과 ABTS radical 소거능이 높았다. 이는 Hwang AR(2019)의 연구에서 페퍼민트차의 DPPH radical 소거능이 뽕잎차보다 더 높았던 것과 Yoo SM(2019)의 연구에서 페퍼민트차의 ABTS radical 소거능이 뽕잎차보다 더 높았던 것과 일치하는 결과이다.

로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 모두 80℃에서 추출했을 때 60℃에서 추출한 것보다 더 높은 항산화 활성이 나타났다. 이러한 결과는 로스팅 처리를 하게 되면 페놀 화합물의 추출을 용이하게 할 수 있다고 한 연구(Yun UJ 등 2012)와 Jung YH 등(2019)의 연구에서 차의 추출 온도가 높아질수록 total polyphenol 함량이 증가하고, DPPH radical 소거능이 높게 나타난 것과 일치하는 결과이다. Phenolic acids와 stilbenes 등과 같은 페놀 화합물은 화학적 보호물질로 작용하여 제품의 유통기한을 연장시켜 주기도 한다(Shahidi F & Ambigaipalan P 2015). 이에 근거하여 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎은 혼합차뿐만 아니라, 다양한 제품에 활용될 수 있을 것이라 생각된다.

2. RSM에 의해 설계된 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 혼합차의 생리활성

로스팅 뽕잎(X1)과 페퍼민트 잎(X2)을 독립변수로 하여 RSM에 의해 설계된 11개의 혼합차 시료들의 total polyphenol 함량, total flavonoid 함량, DPPH radical 소거능, ABTS radical 소거능을 분석하여 각각의 측정값은 Table 4에, 측정값에 대한 회귀식은 Table 5에 제시하였다.

Antioxidant activities of mixture of roasted mulberry leaf (X1) and roasted peppermint leaf (X2) by response surface methodology

Analysis of predicted model equation for antioxidant activities of mixed tea of roasted mulberry and peppermint leaves

Table 4에 제시된 바와 같이 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 혼합차 시료들의 total polyphenol 함량은 21.40∼46.58 mg TAE/g의 범위로 나타났다. 그 가운데 뽕잎 1.00 g과 페퍼민트 잎 0.85 g을 혼합한 6번 시료의 total polyphenol 함량이 46.58 mg TAE/g으로 활성이 가장 높게 나타났다.

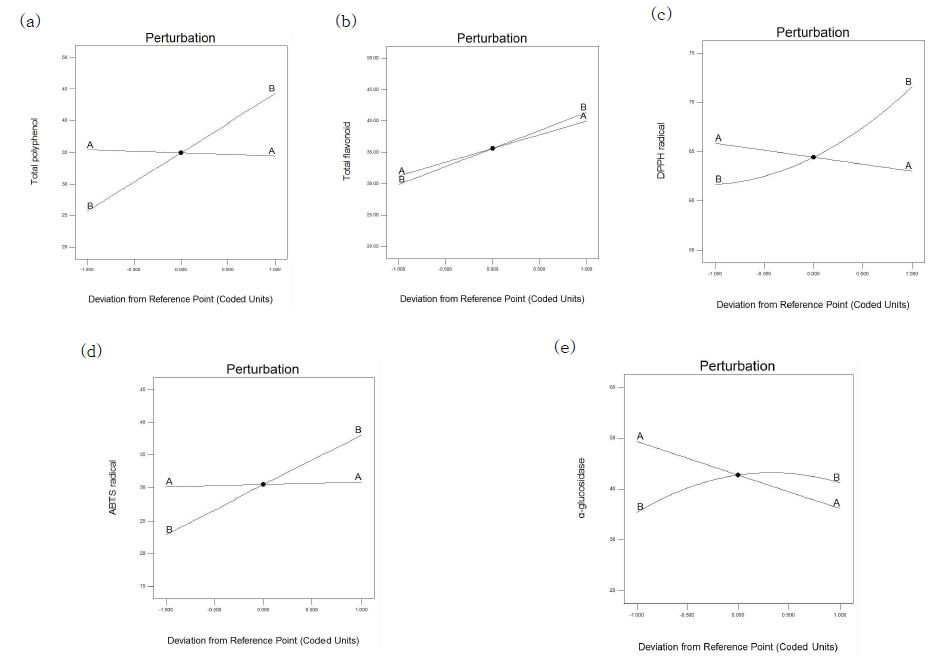

Table 5에 제시된 바와 같이 total polyphenol 함량은 2FI(two factor interaction) model이 선정되었다. 결과에 대한 회귀식의 R2값은 0.9896으로 나타났으며, p값은 <0.0001로 유의하게 나타났다. 또한 Fig. 2-(a)에 제시된 perturbation plot에 따르면 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎(B)이 로스팅 뽕잎(A)보다 total polyphenol 함량에 더 큰 영향을 준 것으로 나타났다.

Perturbation plot of mixture of roasted mulberry leaf (A) and roasted peppermint leaf (B) on total polyphenol (a), total flavonoid (b), DPPH radical scavenging activity (c), ABTS radical scavenging activity (d) and α-glucosidase inhibitory effect (e).

Table 4에 제시된 바와 같이 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 혼합차 시료들의 total flavonoid 함량은 23.29∼45.54 mg QE/g의 범위로 나타났다. 그 가운데 뽕잎 1.50 g과 페퍼민트 잎 0.75 g을 혼합한 11번 시료의 total flavonoid 함량이 45.54 mg QE/g으로 활성이 가장 높게 나타났다.

Table 5에 제시된 바와 같이 total flavonoid 함량은 linear model이 선정되었다. 결과에 대한 회귀식의 R2값은 0.712로 나타났으며, p값은 0.0068로 유의하게 나타났다. 또한 Fig. 2-(b)에 제시된 perturbation plot에 따르면 로스팅 뽕잎과 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎 모두 첨가 비율이 증가할수록 total flavonoid 함량이 높아지는 것으로 나타났다.

Table 4에 제시된 바와 같이 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 혼합차 시료들의 DPPH radical 소거능은 59.50∼74.18%의 범위로 나타났다. 그 가운데 뽕잎 1.00 g과 페퍼민트 잎 0.85 g을 혼합한 6번 시료의 DPPH radical 소거능이 74.18%로 활성이 가장 높게 나타났다.

Table 5에 제시된 바와 같이 DPPH radical 소거능은 quadratic model이 선정되었다. 결과에 대한 회귀식의 R2값은 0.9594로 나타났으며, p값은 0.0003으로 유의하게 나타났다. 또한 Fig. 2-(c)에 제시된 perturbation plot에 따르면 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎이 로스팅 뽕잎보다 DPPH radical 소거능에 더 큰 영향을 준 것으로 나타났다. Lee JS 등(2007)의 연구에서 꾸지뽕나무 잎차의 DPPH radical 소거능이 29.97%로 나타난 것과 본 연구를 비교해 보았을 때 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 혼합시료에서 DPPH radical 소거능이 Lee JS 등(2007)의 꾸지뽕나무 잎차에 비해 높게 나타난 것은 시너지 효과로 생각된다.

Table 4에 제시된 바와 같이 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 혼합차 시료들의 ABTS radical 소거능은 18.91∼40.60%의 범위로 나타났다. 그 가운데 뽕잎 1.00 g과 페퍼민트 잎 0.85 g을 혼합한 6번 시료의 ABTS radical 소거능이 40.60%로 활성이 가장 높게 나타났다.

Table 5에 제시된 바와 같이 ABTS radical 소거능은 linear model이 선정되었다. 결과에 대한 회귀식의 R2값은 0.9747로 나타났으며, p값은 <0.0001로 유의하게 나타났다. 또한 Fig. 2-(d)에 제시된 perturbation plot에 따르면 로스팅 뽕잎과 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎 모두 첨가 비율이 증가할수록 ABTS radical 소거능이 높아지는 것으로 나타났다. 특히 ABTS radical 소거능과 total polyphenol 함량 모두에서 뽕잎 1.00 g과 페퍼민트 잎 0.85 g을 혼합한 6번 시료의 활성이 가장 높게 나타났는데, 이는 total polyphenol 함량과 ABTS radical 소거능 사이에는 높은 상관성을 나타낸다고 보고한 Ham HM 등(2015)의 결과와 일치하는 결과이다.

체내에 활성산소가 축적되면 노화를 비롯한 다양한 질병 유발의 주요 원인으로 작용하며, 체내에 축적된 활성산소는 SOD, CAT, GPX 등의 항산화효소나 항산화제들에 의해 제거될 수 있다(Jang JB 등 2010). 본 연구에서 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 혼합차 시료들의 DPPH radical 소거능이 최대 74.18%로 나타나 항산화제로서의 활용가능성이 있음을 알 수 있었다.

당뇨병 치료를 위해 사용되고 있는 경구 혈당강하제는 인슐린 분비촉진제와 소화관에서 포도당 흡수를 지연시키는 α-glucosidase 저해제로 분류된다(Kim JW 등 2013). 이 중 α-glucosidase 저해제는 이당류의 분해효소를 가역적으로 억제하여 식후 혈당 상승을 완만하게 하는 효과가 있다(Kim HY 등 2011).

따라서 본 연구에서는 로스팅 뽕잎(X1)과 페퍼민트 잎(X2)을 독립변수로 하여 RSM에 의해 설계된 11개의 혼합차 시료들의 α-glucosidase 저해 활성을 측정하여 측정값은 Table 6에, 측정값에 대한 회귀식은 Table 7에 제시하였다. Table 6에 제시된 바와 같이 α-glucosidase 저해 활성은 25.96∼55.88%의 범위로 나타났다. 그 가운데 뽕잎 0.50 g과 페퍼민트 잎 0.75 g을 혼합한 4번 시료의 α-glucosidase 저해 활성이 55.88%로 활성이 가장 높게 나타났다.

α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity of mixed tea of roasted mulberry leaf (X1) and roasted peppermint leaf (X2) by response surface methodology

Analysis of predicted model equation for α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of mixed tea of roasted mulberry and peppermint leaves

Table 7에 제시된 바와 같이 α-glucosidase 저해 활성은 quadratic model이 선정되었다. 결과에 대한 회귀식의 R2값은 0.9405로 나타났으며, p값은 0.0008로 유의하게 나타났다. 또한 Fig. 2에서와 같이 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎(B)이 로스팅 뽕잎(A)보다 α-glucosidase 저해 활성에 더 큰 영향을 준 것으로 나타났다.

Hwang AR(2019)의 연구에서 뽕잎차의 α-glucosidase 저해 활성은 27.37%, 페퍼민트차의 α-glucosidase 저해 활성은 11.34%로 뽕잎차의 α-glucosidase 저해 활성이 페퍼민트차보다 더 높은 것으로 나타났다. 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎을 혼합하여 α-glucosidase 저해 활성(55.88%)을 측정한 본 연구결과와 뽕잎차(27.37%)와 페퍼민트차의 α-glucosidase 저해활성(11.34%)을 각각 측정한 Hwang AR(2019)의 연구를 비교해 보았을 때, 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 혼합 시료에서 α-glucosidase 저해 활성이 Hwang AR(2019)에 비해 높게 나타난 것은 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 혼합에 의한 시너지 효과로 생각된다.

3. RSM에 의해 설계된 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 항산화 활성과 α-glucosidase 저해 활성이 최대로 발현되는 최적 혼합 비율 산출

항산화 활성과 α-glucosidase 저해 활성이 최대로 발현되는 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 최적 혼합비율을 구하기 위해 종속변수로 total polyphenol 함량, total flavonoid 함량, DPPH radical 소거능, ABTS radical 소거능 및 α-glucosidase 저해 활성을 선정하였다.

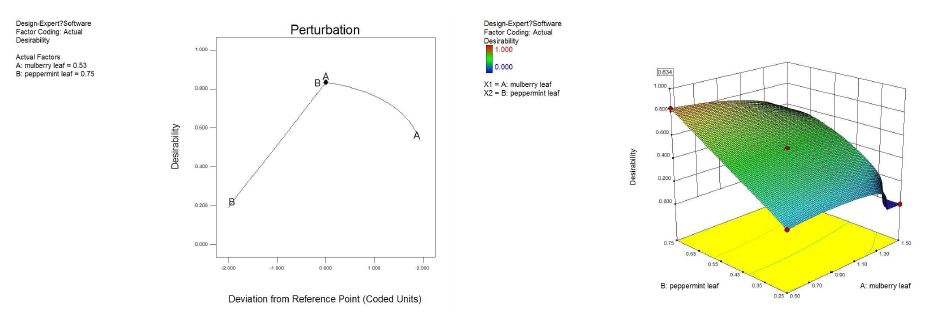

로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 최소 및 최대 범위는 각각 0.50 g∼1.50 g과 0.25 g∼0.75 g으로 설정하였다. 항산화 활성과 α-glucosidase 저해 활성이 최대로 발현되는 최적 혼합 비율을 예측하고자 하였으며, 최고의 desirability를 나타낸 최적점을 선택한 후 지점 예측을 통해 최적 혼합 비율을 산출하였다.

Fig. 3에 제시된 perturbation plot을 보면 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎은 첨가 비율이 증가할수록 항산화 활성과 α-glucosidase 저해 활성을 높이는 요인으로 작용하였으며, 로스팅 뽕잎보다 항산화 활성과 α-glucosidase 저해 활성에 더 큰 영향을 준 것으로 나타났다.

Perturbation plot and 3D response surface model graphs for the effect of mixed tea of roasted mulberry leaf (A) and roasted peppermint leaf (B) on antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity.

항산화 활성과 α-glucosidase 저해 활성이 최대로 발현되는 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 최적 혼합 비율은 로스팅 뽕잎이 0.53 g, 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎이 0.75 g일 때였다. 이때 total polyphenol 함량은 46.37 mg TAE/g, total flavonoid 함량은 37.24 mg QE/g, DPPH radical 소거능은 71.44%, ABTS radical 소거능은 37.66%, α-glucosidase 저해 활성은 53.59%로 예측되었으며, desirability는 0.834였다.

요약 및 결론

본 연구에서는 로스팅 처리를 통해 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 항산화능과 항당뇨능을 강화시킨 후 RSM을 이용하여 생리 활성이 우수한 최적비율의 혼합차를 개발하고자 하였다.

뽕잎과 페퍼민트 모두 5단계로 나누어 로스팅 처리하였다. 온도별로 항산화 활성을 측정한 결과, total polyphenol 함량, total flavonoid 함량, DPPH radical 소거능 및 ABTS radical 소거능 모두 80℃에서 우린 차의 활성이 60℃에서 우린 차보다 높게 나타났다. 또한 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎의 항산화 활성이 로스팅 뽕잎에 비해 우수하게 나타났다.

RSM에 의해 설계된 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎 혼합차 시료들의 생리활성 분석 결과, total polyphenol 함량은 뽕잎 1.00 g과 페퍼민트 잎 0.85 g을 혼합한 6번 시료가 46.58 mg TAE/g으로 가장 높게 나타났으며, total flavonoid 함량은 뽕잎 1.50 g과 페퍼민트 잎 0.75 g을 혼합한 11번 시료가 45.54 mg QE/g으로 가장 높게 나타났다. DPPH radical 소거능과 ABTS radical 소거능은 뽕잎 1.00 g과 페퍼민트 잎 0.85 g을 혼합한 6번 시료가 각각 74.18%, 40.60%로 가장 높게 나타났다. α-Glucosidase 저해 활성은 뽕잎 0.50 g과 페퍼민트 잎 0.75 g을 혼합한 4번 시료가 55.88%로 가장 높게 나타났다.

항산화 활성과 α-glucosidase 저해 활성이 최대로 발현된 로스팅 뽕잎과 페퍼민트 잎의 최적 혼합 비율은 로스팅 뽕잎(A)이 0.53 g, 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎(B)이 0.75 g일 때였다. 이때 total polyphenol 함량은 46.37 mg TAE/g, total flavonoid 함량은 37.24 mg QE/g, DPPH radical 소거능은 71.44%, ABTS radical 소거능은 37.66%, α-glucosidase 저해 활성은 53.59%로 예측되었다.

이상의 결과, 로스팅 뽕잎 0.53 g과 로스팅 페퍼민트 잎 0.75 g의 혼합차는 항산화활성 뿐만 아니라, 혈당개선에도 도움이 되는 기능성 음료로서 활용가치가 있을 것으로 생각된다.

REFERENCES

-

Augšpole I, Dūma M, Cinkmanis I, Ozola B (2018) Herbal teas as a rich source of phenolic compounds. CHEMIJA 29(4): 257-262.

[https://doi.org/10.6001/chemija.v29i4.3841]

-

Barbalho SM, Machado FMVF, Oshiiwa M, Abreu M, Guiger EL, Tomazela P, Goulart RA (2011) Investigation of the effects of peppermint (Mentha piperita) on the biochemical and anthropometric profile of university students. Ciênc Tecnol Aliment, Campinas 31(3): 584-588.

[https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-20612011000300006]

-

Blois MS (1958) Antioxidant determination by the use of a stable free radical. Nature 181(4617): 1199-1200.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/1811199a0]

-

Chae JY, Lee JY, Hoang IS, Whangbo D, Choi PW, Lee WC, Kim JW, Kim SY, Choi SW, Rhee SJ (2003) Analysis of functional components of leaves of different mulberry cultivars. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 32(1): 15-21.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2003.32.1.015]

-

Davis WB (1947) Determination of flavanones in citrus fruits. Anal Chem 19(7): 476-478.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60007a016]

-

Fellegrini N, Roberta R, Min Y, Catherine RE (1999) Screening of dietary carotenoids and carotenoid-rich fruit extracts for antioxidant activities applying 2,2'-azinobis(3-ethylenebenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical cation decolorization assay. Method Enzymol 299: 379-389.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(99)99037-7]

-

Ham HM, Woo KS, Lee BW, Park JY, Sim EY, Kim BJ, Lee CW, Kim SJ, Kim WH, Lee JS, Lee YY (2015) Antioxidant compounds and activities of methanolic extracts from oat cultivars. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 44(11): 1660-1665.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2015.44.11.1660]

-

Hong JY, Park JA (2014) Effect of health status and health behavior on the diabetes mellitus prevalence of Korean adults. Jour of KoCon a 14(10): 198-209.

[https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2014.14.10.198]

-

Hunyadi A, Martins A, Hsieh TJ, Seres A, Zupkó I (2012) Chlorogenic acid and rutin play a major role in the in vivo anti-diabetic activity of Morus alba leaf extract on type II diabetic rats. PloS one 7(11): e50619.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050619]

- Hwang AR (2019) A study on antidiabetic effects of the some commercial teas. MS Thesis Kyonggi University, Seoul. pp 21-27.

- Jang JB, Park OR, Yun TE (2010) Free radicals, physical performance, aging and antioxidants. The Korean Journal of Ideal Body & Beauty 2(1): 19-27.

- Joo SJ, Choi KJ, Kim KS, Park SG, Kim TS, Oh MH, Lee SS, Ko JW (2002) Characteristics of mixed tea prepared with several herbs cultivated in Korea. Korean J Food Preserv 9(4): 400-405.

-

Jung YH, Han JS, Kim AJ (2019) Quality evaluation and antioxidant activity of inner beauty tea prepared from roasted lotus root and burdock. Asian J Beauty Cosmetol 17(2): 235-245.

[https://doi.org/10.20402/ajbc.2019.0285]

- KAFFTC (Korea Agro-Fisheries & Food Trade Corporation) (2019) 2018 Processed Food Segment Market Status – variety of tea http://www.atfis.or.kr, (accessed on 8. 21. 2019)

-

Kim AJ, Kang HJ, Kim MJ (2016) Development of optimization mixture tea prepared with roasting mulberry leaf and fruit. Korean J Food Nutr 29(6): 1040-1049.

[https://doi.org/10.9799/ksfan.2016.29.6.1040]

-

Kim DC, In MJ, Chae HJ (2010) Preparation of mulberry leaves tea and its quality characteristics. J Appl Biol Chem 53(1): 56-59.

[https://doi.org/10.3839/jabc.2010.010]

-

Kim HY, Lim SH, Park YH, Ham HJ, Lee KJ, Park DS, Kim KH, Kim SM (2011) Screening of α-amylase, α-glucosidase and lipase inhibitory activity with Gangwon-do wild plants extracts. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 40(2): 308-315.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2011.40.2.308]

- Kim JS (2009) Quality properties of lotus and mulberry leaves teas fermented by mycelial Paecilomyces japonica. Ph D Dissertation Sunchon National University, Jeollanam-do. pp 53-63.

-

Kim JW, Kim JK, Song IS, Kwon ES, Youn KS (2013) Comparison of antioxidant and physiological properties of Jerusalem artichoke leaves with different extraction processes. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 42(1): 68-75.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2013.42.1.068]

- Lee JS, Han GC, Han GP, Kozukue N (2007) The antioxidant activity and total polyphenol content of Cudrania tricuspidata. J East Asian Soc Dietary Life 17(5): 696-702.

-

Lee KH, Kim MJ, Kim AJ (2014) Physicochemical composition and antioxidative activities of Rhynchosia nulubilis according to roasting temperature. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr 43(5): 675-681.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2014.43.5.675]

- Li T, Zhang X, Song Y, Liu J (2005) A microplate-based screening method for α-glucosidase inhibitors. China J Clin Pharm Ther 10(10): 1129-1131.

- Loolaie M, Moasefi N, Rasouli H, Adibi H (2017) Peppermint and its functionality: A review. Arch Clin Microbiol 8(4): 54.

- Sailesh KS, Padmanabha (2014) A comparative study of the anti diabetic effect of oral administration of cinnamon, nutmeg and peppermint in Wistar Albino rats. IJHSR 4(2): 61-67.

-

Saleem A, Durrani AI, Fatima BA, Irfan A, Noreen M, Kamran A, Duaa A (2019) Preparation of marketable functional food to control hypertension using basil(Ocimum basillium) and peppermint(Mentha piperita). IJIST 1(1): 15-32.

[https://doi.org/10.33411/IJIST/2019010102]

-

Shahidi F, Ambigaipalan P (2015) Phenolics and polyphenolics in foods, beverages and spices: Antioxidant activity and health effects–A review. J Funct Foods 18: 820-897.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2015.06.018]

- Shim JU, Lim KT (2008) Glycoprotein isolated from Morus indica Linne enhances detoxicant enzyme activities and lowers plasma cholesterol in ICR mice. Korean J Food Sci Technol 40(6): 691-695.

- Shin KS (2012) Immunostimulating plant polysaccharides: Macrophage immunomodulation and its possible mechanism. Food Sci Ind 45(1): 12-22.

- Singleton VL, Rossi JA (1965) Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am J Enol Vitic 16(3): 144-158.

- WHO (World Health Organization) (2003) WHO Technical Report Series 916: Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation, Geneva, Switzerland. p 11.

- WHO (World Health Organization) (2018) World Health Statistics 2018: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. pp 5-8.

- Yoo SM (2019) A study on the effect of inner beauty food of commercial teas. MS Thesis Kyounggi University, Seoul. pp 17-21.

-

Yun UJ, Yang SY, Lee HS, Hong CO, Lee KW (2012) Optimal roasting conditions for maximizing the quality of tea leached from high functional Perilla frutescens leaves. Korean J Food Sci Technol 44(1): 34-40.

[https://doi.org/10.9721/KJFST.2012.44.1.034]